This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Here we are: the third and last of my musings on Jurassic Park. The previous of my two articles featured my personal take on the backstory and run-up to the movie, and my reaction to the movie itself. That second article finished by discussing various of the visual effects featured in the movie – and this is where we pick things up today…

As per previous articles, I’m mostly filling this piece with pictures of toys from my own collection. Here’s the Tyrannosaurus again. With box. Credit: Darren Naish

Part of what made Jurassic Park such a phenomenon was the interest that everyone had in its effects. Features on such things as BBC’s 9 o’clock news (or was it ITV’s 10 o’clock news?) not only helped drum up hype but made Jurassic Park newsy. This isn’t Just Another Movie, but the dawning of a revolution in cinematic entertainment. I do remember there being similar mainstream interest in the effects of Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and to a degree in Terminator 2: Judgement Day, two movies I also know embarrassingly well. And you’ll know that T2’s effects can certainly be considered linked to those of Jurassic Park.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

If seriously interested in the backstory to Jurassic Park, you absolutely must get hold of Shay & Duncan (1993). It’s a great book. Credit: Darren Naish

The big question: how – but how!! – had Spielberg and his buddies given us such real, living, breathing dinosaurs? Even at the time it was obvious that the film was historic as goes effects and visuals. Those of us who’ve read and seen a million ‘making of’ magazine articles, TV spots and youtube videos (or have read Don Shay and Jody Duncan’s outstandingly good The Making of Jurassic Park) are familiar with the story of how Phil Tippett’s original stop-motion puppets were superseded but eventually made integral to the CG process, of how ILM broke new ground with their innovations in CG, and of the amazing job on the robotics and models made at Stan Winston’s studio (Shay & Duncan 1993). I might be known, rightly or not, as a zoology nerd, but I’ve spent some significant part of my life watching the films of the Stars Wars, Alien and Terminator franchises, in which case seeing creative forces the likes of ILM, Tippett and Stan Winston work together is basically a dream come true. Damn, did they deliver.

Carnotaurus is not in the original Jurassic Park book or movie, but this toy appeared relatively early in the range. It’s not bad, though the hands are a fabrication compared to what the animal was actually like. The toy comes with a range of metallic restraining devices that look a bit cruel, or perverse, depending on your point of view. Credit: Darren Naish

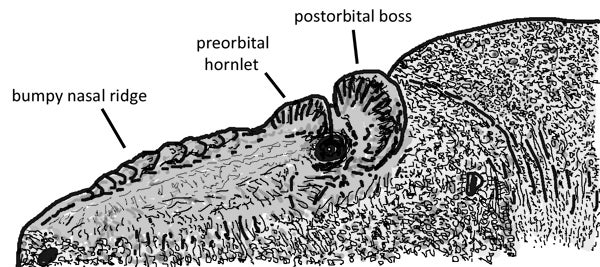

It’s not just the mechanics and craftmanship that makes Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs so good, it’s the fact that there was a real and obvious effort throughout the making of this film to – some artistic license besides (like those seismic T. rex footfalls… and that dilophosaur) – to make the dinosaurs about as accurate as they could be. Sure, there are things they either got wrong, or modified for cinematic effect (examples: Tyrannosaurus didn’t really have a triangular eye horn like that, the hands of a Triceratops wouldn’t look as elephantine as they do in the movie, the brachiosaur was super-sized for effect and should have had far slimmer limbs, and dromaeosaurs couldn’t curl their lips to create a nefarious facial expression) but – by and large – those behind the movie did work hard to give us ‘real’ dinosaurs. It’s almost as if they cared. Speaking myself as someone who cares about the way dinosaur life appearance is portrayed, the big win of Jurassic Park is that it gave naïve audiences the horizontal-bodied, bird-like dinosaurs of the Renaissance, not the tail-dragging, chubby behemoths of yore. If you were a kid at the time Jurassic Park came out, and hence have always felt familiar with horizontal-bodied, fairly accurate-looking dinosaurs, count yourself lucky.

Tyrannosaurus did not have the large, triangular horn shown in Jurassic Park. Instead, there were big, horn-covered hornlets or bosses, as shown here. The reconstruction here is traced from the skull of AMNH 5027, the specimen on display in New York. Credit: Darren Naish

So, not only do we have a movie that brings a view of dinosaurs as active, dynamic, warm-blooded, social animals to its audience, it also gives them dinosaurs that look pretty close to the genuine articles, the big disclaimer here being – yeah – the feather issue (see the first part of this series of articles).

Stegosaurus doesn’t appear in Jurassic Park (though its name – wrongly spelt Stegasaurus – does appear in the scene where Nedry is stealing the embryos from storage). It is in the sequel though (in super-sized formed). A toy stegosaur was, however, featured as part of the original toy range. Its face is not very accurate at all. Credit: Darren Naish

And it’s at this point that I need to stop talking about Jurassic Park and comment briefly on its various sequels, including of course the Jurassic World films. I’ll say that 1997’s The Lost World: Jurassic Park has some good bits (among them the dinosaur capture scene) but otherwise has too much hokum to be likeable (the gymnastic scene, the ‘I’ve stepped in something’ scene, Burke’s death, the Godzilla comes to San Diego scene, basically everything on the ship…). Jurassic Park III is, ugh, just terrible.

And Jurassic World? As I’ve said at length elsewhere (here’s my infamous CNN piece of 2015), I’m basically disappointed with the people behind that movie for opting to stick with the safe ‘brand look’ of their dinosaurs and not go with the reboot they could have. Scaly-skinned dromaeosaurs might have been excusable for 1993, but a 2015 movie could have given us something better.

The original Kenner Stegosaurus toy (yes, I still have the boxes...) is one of several in the range that has a ‘battle damage’ feature where a large chunk of external surface can be removed to reveal musculature and bones beneath (yuck!). The removeable chunk is made from a different plastic and, as you can see here, ages differently from the rest of the toy. The toy also has a single row of plates, a feature based on Stephen Czerkas’s proposed of 1987 (and not considered correct today: the plates were arranged in a staggered, asymmetrical pattern). Credit: Darren Naish

Yes, of course movie-makers are perfectly entitled to create whatever fictional universe they like given that it’s only a movie (yaaawn), but I can’t help but be frustrated as someone who cares about public education and – boy – what a contrast to the approach behind Jurassic Park. I’m not just talking about the lack of feathers on the dromaeosaurs: pretty much all the Jurassic World animals are hideous caricatures; even the T. rex somehow looks less good than the version of 1993. And in contrast to Jurassic Park, I just don’t think that Jurassic World is a good movie. What about the new one (Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom)? It should be clear from all I’ve said in these articles that I do actually enjoy movies and I watch them often. At the time of writing, Solo, my several viewings of Avengers: Infinity War and a nostalgic re-viewing of Inner Space from two evenings ago are all fresh in my mind. And, sad to say, Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom just doesn’t interest me.

There are even people who have kept a select few original Jurassic Park toys inside unopened packets. Weird, huh? Credit: Darren Naish

Will we ever see a dinosaur film that does anything like 1993’s Jurassic Park ever again? The theme of Jurassic Park, at least, has been carried through to other projects, arguably among them the Walking With franchise and the travelling (but presently London-based) interactive attraction Dinosaurs in the Wild (which has just had its London run extended by a few weeks). But a new movie that’s actually as good, exciting and ground-breaking as that of summer 1993? It could be done. But my hopes are not high.

Dinosaurs in the Wild presents the public with a more modern, accurate view of the Mesozoic world than anything featured in the Jurassic Park movies, and was created with a fraction of its budget. What if a big-budget movie – featuring the exciting, accurate dinosaurs of reality – were to appear? We can but dream. Credit: Darren Naish

For more on Jurassic Park at Tet Zoo, see...

For relevant Tet Zoo articles on dinosaurs (there is a lot more in the archives), see...

Did dinosaurs and pterosaurs practise mutual sexual selection?

Ryan et al.'s New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: a review

Junk in the trunk: why sauropod dinosaurs did not possess trunks (redux, 2012)

Dinosaurs and their exaggerated structures: species recognition aids, or sexual display devices?

Artistic Depictions of Dinosaurs Have Undergone Two Revolutions

Yi qi Is Neat But Might Not Have Been the Black Screaming Dino-Dragon of Death

The Integrated Maniraptoran, Part 3: Feathers Did Not Evolve in an Aerodynamic Context

Refs - -

Shay, D. & Duncan, J. 1993. The Making of Jurassic Park. Boxtree, London.