This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

If I were an apple I would be the kind of apple that didn’t fall very far from the tree. My father is a neuroscientist, my mother is a cell biologist and I have been working in labs and academic research settings since high school.

As a field scientist studying snow and permafrost in Alaska, I often tell people that I have the coolest job in the world. Simultaneously, I experience some glaring small scale and institutional gender inequity issues at work. For example, there are a limited number of senior female role models.

Lucky for me, my mother is a tenured professor at Yale University who leads a laboratory that studies cancer treatments, among other things. After navigating the system of academic science for over four decades—a system that wasn’t designed for her—she remains extraordinarily successful. While we often touch on these issues in passing, I thought I might gain some valuable insights by having a more in-depth conversation with my mom. To be clear, this is a conversation between two white women and does not even begin to address challenges in science faced by other underrepresented groups.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

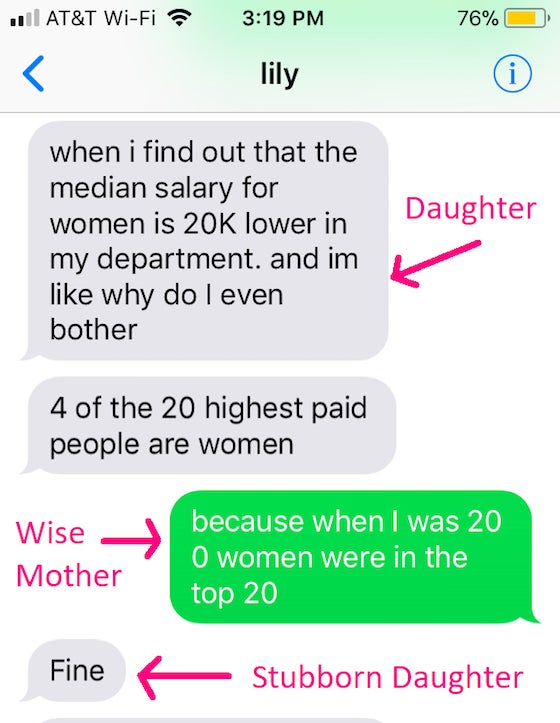

A recent text conversation with my mom went like this:

(This interview has been edited and condensed.)

Lily Cohen: Mom, why did you become a scientist?

Barbara Ehrlich: I always thought I was going to become a scientist. I remember thinking of myself in a laboratory with colored fluids bubbling—this ten-year-old idea of what a laboratory is. After my second year in college I got a summer job at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. It was a terrible job. I was a chamber maid in the dormitory, because it was the only job that they gave girls back in those days. Boys could work in the apparatus department or in the photography lab, but that wasn't for us. Boys were allowed to go to a lecture during their break, and girls weren't allowed. That was 1972, just about the time when the “women's lib” movement was becoming interesting.

I lobbied one of the professors and became the only girl allowed to go to lectures. I got really excited about the kinds of things people did. At that time I was a math major, and I was pretty aware that I was a reasonable mathematician, but I would never be an outstanding mathematician. After that summer I went back to college and asked Helen Cserr, a professor who had taught in my animal physiology class, if she could help me find a lab. She asked if I would be interested in working in her lab, and it was probably the best thing that ever happened. I loved being in a lab—I looked forward to all the time I spent there.

LC: Sometimes I lose perspective, because obviously a lot has changed in a positive direction. I get focused on how far we still need to come until there is equity or equality, so it's good to hear these stories.

BE: When I was in college at Brown, there was only one female tenured faculty member at the university. Helen had to be pretty tough. She wasn't a complainer, but it was clear that she had to fight for everything she got at the university. She was part of a sex discrimination case because women were denied tenure. In the case of Helen there were tapes of a meeting where they said she didn’t need to have tenure because her husband was a physician. This was post Nixon, and they tried to delete parts of the tape, just like Nixon.

LC: Was becoming a scientist in this environment at all daunting to you?

BE: I think I was a sleep walker in some of these issues. Because Helen had been encouraging, it didn't occur to me that I should be worried. I can’t explain why.

In graduate school my class started with ten students. At the end of the first year we had a qualifying exam, and all five of the males passed and only one female passed: me. That was the first time I was really struck by something like that. I thought I was pretty lucky, but on the other hand I rationalized it saying that the other women had all made mistakes. It was sort of a shock, but I was more interested in doing the science. I didn't stop to get angry, I just kept moving forward because my advisor was incredibly supportive.

LC: When I was growing up, you talked a lot about gender issues at work. I would often blow them off, which I now regret, and I'm sorry. Is there a moment when you started paying attention, because clearly something changed?

BE: There was no one event that made me become much more vocal. There were all these things that piled on and I tried to ignore them because I really wanted to just do the science. With time it got so overwhelming that I just couldn't ignore it.

During college, in the lab next to Helen's lab there was a husband/wife team where the husband was the scientist and the wife was the technician. I told them I was going to go to grad school in physiology or biophysics and they looked at me and shook their heads and said, you don't need to do that, you just need to marry a biophysicist.

Early on I remember going to the biophysical society meeting where there were about 1000 people and only a handful of women. I was standing near a stairwell with three of my female friends and as the men would come off the escalator, 90 percent of them looked at us and said things like "oh my god, are you plotting against us?" They made comments about how having four women standing together at a scientific meeting was threatening.

LC: Grab your torch and pitchfork.

BE: For all 11 years that I was a professor at the University of Connecticut, I defined the lowest-paid person in my rank at the medical school. I asked to have my salary raised to the 50th percentile and the chairman refused in a very aggressive manner.

As a professor I was asked to be on many, many committees because they were just realizing they had to have women on committees, but there weren't that many women. I would walk in the room and there would be like nine other people, all chairman or deans and I’m an assistant professor. It was clear that I was the token. I tried to leverage that, but it was hard to get your voice heard.

It seemed like the males in my class all had their careers advance faster than mine. I watched them moving faster. Though if this were a case of the tortoise and the hare, the tortoise has finished the race just fine, thank you.

LC: You've been watching me struggle with gender inequity issues as I am starting my career in science. What is it like to watch me deal with some of the same issues that you dealt with?

BE: I’m going to tell you a story that you may remember when we went to see this movie called Mona Lisa Smile. It was about a women professor at one of the all-girls universities and how hard it was to be an unmarried professor and making her way. At the end of the movie I was crying. You looked over at me and said, “mom, this was not a sad movie, why are you crying?” I said, “this is a movie about 1955, and I still say the same things to my students in 1995.”* I had this very deep grief. (*Mona Lisa Smile actually came out in 2003.)

LC: Do you think things have changed a lot?

BE: Absolutely. For example, when I was pregnant with you, I was an assistant professor at the University of Connecticut, which had no policy for maternity leave for faculty. They didn't know what to do with me. Now the glass ceiling has moved. For my mother it was getting to university, now getting tenure is still a barrier. It’s not as bad as it used to be.

I'm an incredible optimist and part of my not wanting to embrace the negative parts is because I really wanted to look at the world as 3/4 cup full. I feel like I now face not only sexism but also ageism. It doesn't stop me from moving forward. Do I get discouraged, yes, but I’m not going to let them get me down.

You know that toy that you had that looked like an ostrich egg and had a weight in the bottom? If you pushed it over it always came back up. I feel like that.

LC: As you know I'm considering taking a break from science. Are you disappointed in me for not getting back up, for not persisting?

BE: No, no absolutely not. You can make an impact on the world in many different ways.

LC: What do you love most about science?

BE: I love puzzles. The two things I really love are making people laugh, and finding out the answer to a puzzle or a question. Plus, I love having young people come through the lab and helping them learn how to be a scientist.