This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

As a long-term reader of Tet Zoo you might be familiar with the idea that artistic depictions of fossil animals – broadly included within the collective term palaeoart… or paleoart – have very frequently featured suspiciously samey-looking organisms. Colour schemes, poses, pieces of behaviour, backgrounds and specific compositions have been depicted again and again as if this given set of characteristics concerns fact or reality, when in truthfulness we know that they are speculative and actually down to artistic whimsy and a quest for what looks about right.

Scenes from PopPalaeo: much-enlarged, 3D-printed jaw of Mesozoic mammaliaform Palaeoxonodon ooliticus, brought along by Elsa Panciroli (specimen provided courtesy of describers Roger Close et al. and National Museum of Scotland), with conference-goers in the background, and the opening slide from my talk (which is online here). Credit: Darren Naish

These repeated themes of detail, composition and design have become known as palaeoart memes, and in a talk given at the Popularising Palaeontology event, held at King’s College London in September 2016, I put forward an argument that palaeoart memes might actually tell us a lot more than the mere fact that artists sometimes copy the efforts of their predecessors. Popularising Palaeontology (follow #PopPalaeo on twitter) has an excellent website where videos of virtually all of the talks (including mine) can be seen: please go here.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Palaeoart memes can be seen across palaeoartistry, in the technical, semi-technical and popular literature, though they are by far most common in the popular literature. I should say, for the few of you that don’t know, that the term meme refers to an idea or piece of behaviour that’s transmitted from one person to another; it’s essentially the cultural version of a gene.

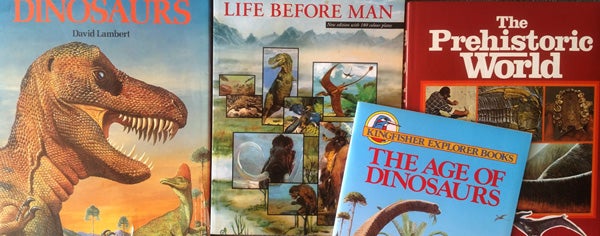

There are a lot of books on dinosaurs (and other prehistoric animals) out there. Some of them include art done by dedicated, expert individuals. Others do not. Credit: Darren Naish

Let’s begin all of this by looking at a few of my favourite palaeoart memes. Some of these will be familiar to long-time Tet Zoo readers and have been covered here before (see links below). I should say that there are actually tens if not hundreds to choose from; I aim (when time and opportunity allows) to catalogue them properly.

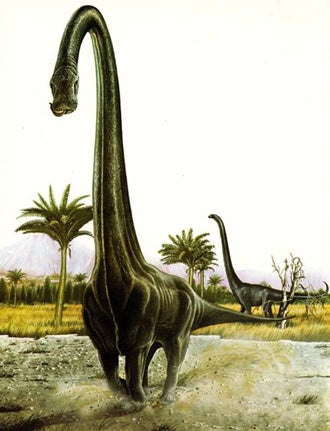

The original freaky giraffoid Barosaurus, by Bernard Robinson. Credit: Bartram et al. 1975

The freaky giraffoid Barosaurus meme. We begin with the so-called ‘freaky giraffoid’ version of Barosaurus, a Late Jurassic diplodocid sauropod, known to have been similar to its close relative Diplodocus. However, for a time spanning some three decades in the late 20th century, Barosaurus was repeatedly shown as being proportionally short-tailed and with an erect, muscular, thick-based neck that curved in an inverted U in its upper part and possessed a ventral raphe and frill (a raphe is a ridge of tissue that marks the union of two halves). This view of Barosaurus first appeared in 1975 in a (really very nice) illustration by Bernard Robinson. It then reappeared throughout the 70s and 80s. Its youngest appearance (of which I’m aware) is from 1995 when it was depicted by Zdeněk Burian.

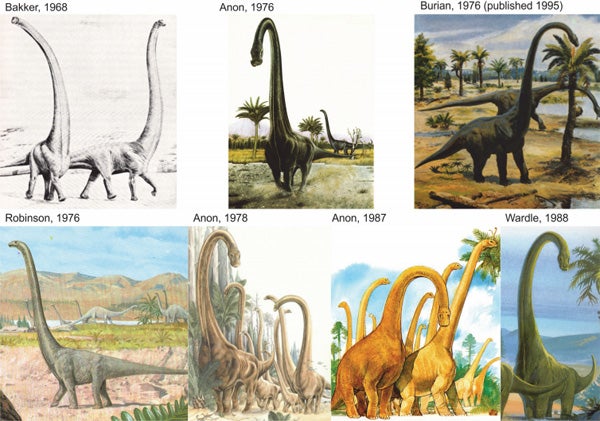

The composite of freaky giraffoid barosaurs used in Witton et al. (2014). We had not succeeded at the time in identifying the artist of the image in the middle of the upper row, but since have, and have since discovered that it was first published in 1975, not 1976; it should say 'Robinson 1975'. Credit: Witton et al. 2014

I contend that the perpetuation of the ‘freaky giraffoid’ Barosaurus demonstrates that the artists concerned simply did not have access to accurate information on this animal. Even in 1975 it was well established that Barosaurus was Diplodocus-like, so if you’re thinking that these artists were screwing things up because the general anatomy and affinities of Barosaurus were unknown -- nope. In Richard Swan Lull’s monograph on Barosaurus from 1919, this dinosaur is repeatedly compared with Diplodocus and said to be far more like it than to other sauropods known at the time (Lull 1919).

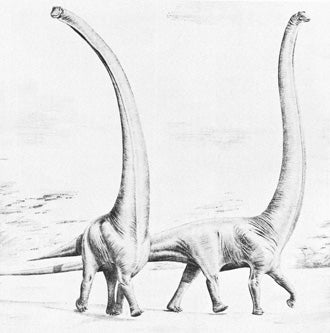

Barosaurus as illustrated by Robert Bakker in 1968. The animal on the left is not short-tailed at all, but foreshortened. An iconic illustration of the Dinosaur Renaissance. Credit: Robert Bakker Discovery

What I think happened is that Robinson initiated a meme by basing a rendition of Barosaurus on a much-reproduced earlier illustration: namely, the fast-walking Barosaurus pair illustrated by Robert Bakker in 1968, and republished in numerous popular, semi-technical and technical publications throughout the 1970s and 80s. One of Bakker’s barosaurs is shown foreshortened, in three-quarter view, and this makes it look short-tailed; it’s also shown as having a very thick-based, mast-like neck with a ventral raphe. So, Robinson bases an illustration on a misunderstanding of an illustration by Bakker, and everyone then followed Robinson. This copying is supported by the repeat appearance of the particular trees that Robinson illustrated too (those trees are novel to Robinson).

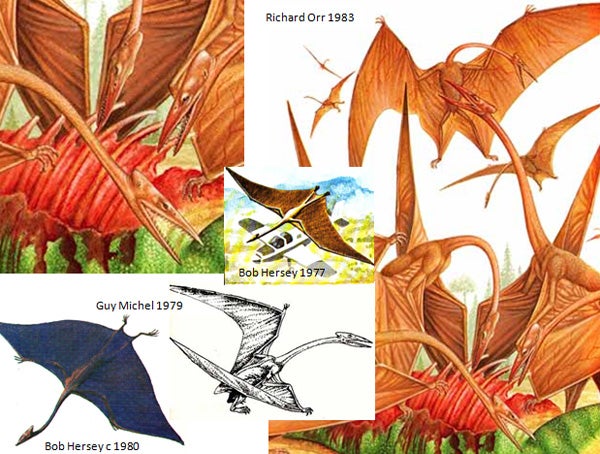

Quetzalcoatlus as the demonic nightmare beast that wants to eat your soul, a montage showing most (but not all) of the images. Credit: Richard Orr, Bob Hersey, Guy Michel

The demonic Quetzalcoatlus meme. Another of my favourite memes concerns the so-called ‘demonic Quetzalcoatlus’. We know today that Quetzalcoatlus was a stork-billed, long-necked, toothless pterosaur, apparently with a laterally compressed dorsal crest. But a number of illustrations from the 1970s, 80s and 90s depict it as a short-headed, toothed creature with a rounded bony crest. These illustrations typically show it as being red, or at least red-brown, the overall impression being of a hideous nightmare creature that absorbs the souls of baby dinosaurs.

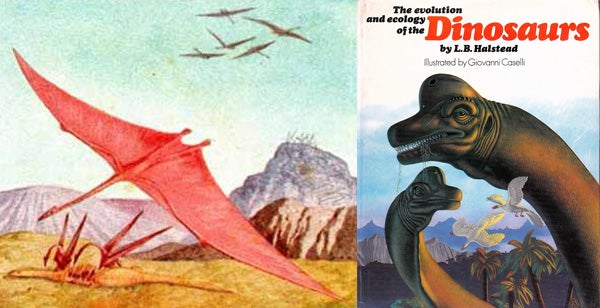

Giovanni Caselli's meme-spawning demonic azhdarchid, with the cover of the source volume at right (Halstead 1975). Credit: Halstead 1975

By following these images through the literature, I found the oldest – the ‘original’ – to be a 1975 illustration by Giovanni Caselli (Halstead 1975). From where, then, did Caselli gain this view of Quetzalcoatlus? I can confirm through correspondence that he simply invented it, being asked at the last minute (and with no information whatsoever, other than that he was illustrating a giant pterosaur from the USA, thought to have some kind of ecological association with sauropod dinosaur bones) to illustrate the animal for a popular book. Other artists used this piece for reference, and a meme was born.

Some rather more modern renditions of azhdarchid pterosaurs, incorporating data from Witton & Naish (2008, 2013). Credit: Mark Witton, Witton & Naish 2008

The black and white Phorusrhacos meme. Moving back to dinosaurs, let’s now look at the meme whereby Phorusrhacos – a giant predatory flightless bird from the Miocene of Argentina – has repeatedly been depicted with a striking black and white livery, and typically with yellow and red bare skin around the base of its bill. This meme appears to have been initiated by Zdeněk Burian who depicted Phorusrhacos this way on several separate occasions. Burian’s artwork – that featured in books of the 1960s and 70s in particular – is technically amazing, widely consulted and highly popular. A huge number of post-Burian Phorusrhacos depictions show it exactly as he did and the meme has persisted almost to modern times.

Composite showing just some of the black and white Phorusrhacos illustrations out there. The ones that started it are the Charles Knight illustration at upper left and the two Burian pieces at centre and right of the top row. Credit: Charles Knight, Zdeněk Burian, Jan Sovak, Ray Harryhausen

There’s nothing technically ‘wrong’ with this view of Phorusrhacos, but there’s also no particular reason to regard it as ‘right’, either. It’s non-controversially agreed that Phorusrhacos and its kin are close relatives of the living seriemas, a fact requiring that our view of Phorusrhacos in life should be based (in part) on these birds. We might predict, then, that Phorusrhacos was mostly brown or grey with dark wingtips, that it had barring somewhere on its plumage, and that it possessed vaned tail feathers arranged in fan-like fashion, not the shaggy, emu-like tail that Burian depicted. To restate: Burian’s reconstruction is fine as a speculative take on this bird but there’s no reason to favour it as an especially likely one. It should not be copied as if it’s valid, as if it reflects the ‘true appearance’ of this animal.

I'm not saying that Phorusrhacos (and kin) must have looked like a modern seriema as goes plumage and hue (the photo shows Cariama cristata), but it's a default assumption that's more likely to be correct than the black and white, shaggy-tailed meme. Credit: Manfred Werner, Tsui Wikimedia (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

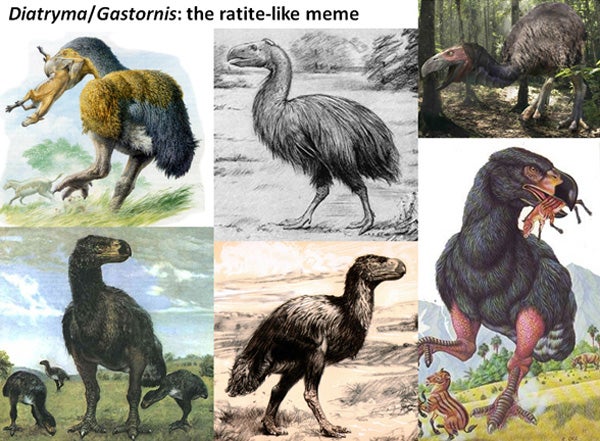

The cassowary-like Gastornis/Diatryma meme. Very similar things could be said about palaeoartistic depictions of another giant extinct bird, namely the Paleogene taxon Gastornis or Diatryma. These two names are increasingly regarded as synonymous, with Gastornis (first used for European taxa) having priority over Diatryma (first used for North American taxa).

Gastornis/Diatryma as reconstructed with dark, shaggy plumage and a ratite-like look. The oldest of these is the image in the middle of the upper row (from Matthew & Granger 1917). The others are by John Sibbick (far left, upper row), Peter Minister (far right, upper row), Zdeněk Burian (the left and centre images in the bottom row), Richard Orr (far right, bottom row). Credit: John Sibbick, Matthew & Granger 1917, Peter Minister, Zdeněk Burian, Richard Orr

Anyway, Gastornis/Diatryma has repeatedly been portrayed as ratite-like, with a dark, shaggy, cassowary-like plumage and naked skin on the face. This view was initiated by William Matthew and Walter Granger in 1917 following the inclusion within their paper of artwork depicting a superficially cassowary-like, shaggy-plumaged, bare-headed Diatryma (Matthew & Granger 1917); this view of the bird was then seemingly endorsed by Cockerell’s (1923) description of long, dark, hair-like filaments thought to be Diatryma feathers. The image of the cassowary-like Diatryma was then lifted by Gerhard Heilmann (thereby marking its transition to the popular literature), and from there adopted by Burian; the rest is history since it then became another palaeoart meme, depicted in countless pieces of art.

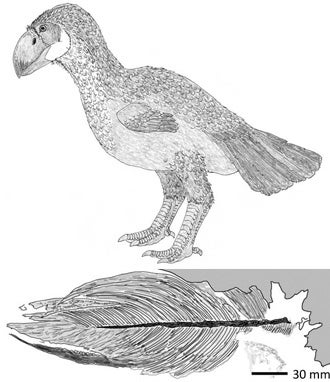

Gastornis/Diatryma more likely looked like a galloanserine - as restored here - than a ratite [reconstruction from my giant in-prep textbook, on which go here]. A giant, vaned feather from the Green River Formation of Wyoming seems to be consistent with this argument. Credit: Darren Naish

And it persisted long after it was shown (in 1930) that those dark filaments were plant fragments (Wetmore 1930), and until long after it came to be appreciated that Gastornis/Diatryma is almost certainly a member of Galloanserae, the group that includes waterfowl and gamebirds. Again, it’s not impossible that Gastornis/Diatryma was radically odd and in possession of a unique shaggy plumage, but it’s far more likely that it had the sort of feathering typical of galloanserines: namely remiges, rectrices, and non-shaggy body feathers. A giant fossil feather from the Green River Formation – quite plausibly belonging to Gastornis/Diatryma – provides support for this contention. While I’m here, similar things could be said about Sylviornis, by the way.

As will be obvious by now, the perpetuation of these memes mostly reflects copying, this ranging from outright plagiarism to the capturing of one aspect of a predecessor’s work, most typically the colour scheme. However, there’s more to the issue than this.

Images of the true, stork-faced Quetzalcoatlus had appeared in the literature by 1977 or 1978. This image accompanied an article in Discovery magazine (Langston 1978). Credit: Langston 1978

Inertia, and the problem with (some) consultants. Palaeoart memes very often provide key insight into what palaeoartists were advised or told to do at any one time. What we’ve seen so far shows how data contradicting the construction and perpetuation of the images concerned was in existence either when the images were created, or shortly afterwards. Barosaurus should not have been illustrated as a ‘freaky giraffoid’, even in 1975; the demonic Quetzalcoatlus was redundant beyond 1977 or 1978 (when a long-jawed reconstruction was published by Wann Langston), Burian’s black and white Phorusrhacos was a remarkably left-field speculation even when it first appeared in 1956, and the cassowary-like Gastornis/Diatryma was demolished gradually after 1930. In short, all of the memes persisted because of inertia, not because there was good, or any, data supporting them.

Books relevant to the issues at hand. All contain some really outstanding – albeit sometimes very weird – artwork. Credit: Darren Naish

Here’s where we come to a problem. The vast majority of the products containing these images – books, that is – were checked by technically qualified palaeontologists. By, that is, people who were supposed to be giving things the ‘ok’, and providing artists with information when they couldn’t get it themselves. What I’m saying here is that paid consultants have very frequently failed the artists they were supposedly working with, and indeed regularly continue to do so.

Yeah yeah. Shut up. Credit: Naish & Barrett 2016

Yes, it’s a dirty little secret that I dislike drawing attention to, but many (not all) scientists employed as consultants actually do not care about the illustrations that go into the books they work on, or are lacking the expertise, knowledge or experience relevant to the depicting of extinct animals in life. The latter isn’t an unfair accusation: we can’t all be experts on everything, and many very excellent and accomplished scientists simply do not work on, or have any special interest in, the science and art of the reconstruction process. Nevertheless, this issue should be kept in mind and repeated when appropriate: many consultants have not done the job publishers were expecting them to, and it’s not necessarily the fault of palaeoartists that they have sometimes produced inaccurate work. And, yes, I know I’m treading on thin ice given a certain recent book cover… that’s a different case though.

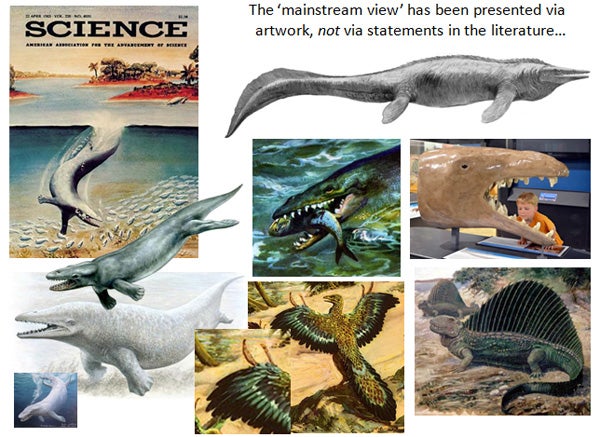

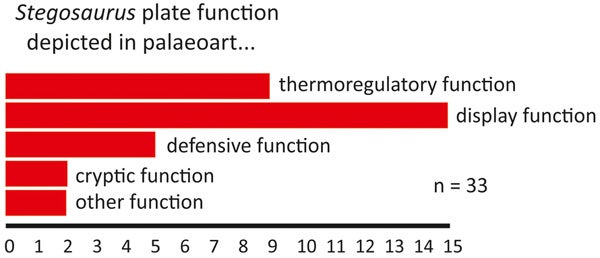

Palaeoart and the unspoken status quo. Moving on, palaeoart memes might be more important in terms of studying palaeontology than has typically been realised. True, memes like those discussed above are very often perpetuated due to copying. But what’s also true is that palaeoartistic images (often perpetuated through memes) frequently, in fact commonly, depict the favoured hypothesis – the accepted status quo – of any one time, even when that hypothesis isn’t written about. Not only do palaeoartistic images portray favoured hypotheses to the public, they are also, sometimes, the only depictions of these hypotheses.

Some ideas that - based on the popular palaeontological literature - seem 'accepted' are not really accepted at all, it's just that artwork is (typically) the only venue in which they've been portrayed; they have not been discussed much, if at all, in the technical literature. Examples: Pakicetus looked like a seal-tapir hybrid, Basilosaurus had a skeletal-looking face, Archaeopteryx had long, scaly fingers. Credit: Charles Knight, Zdeněk Burian, John Sibbick

Look at how feathering was long portrayed on Archaeopteryx (those unfeathered, scaly fingers…), how skin textures were depicted on stem-mammals like Dimetrodon and Lystrosaurus, how the faces of early cetaceans like Basilosaurus were shrink-wrapped and shown without lips or extensive nasal tissue, how mosasaurs were always shown with a serrated frill, and so and on and on. These were all issues that people thought about, but the fact is that scientists essentially never had good cause to write much if anything about them, leaving artists with the job of actually conveying what was thought most likely by the community at the time.

The logical question that emerges next is whether the depictions favoured in palaeoart (and, again, perpetuated across memes) then actually feed back into the science. Could it be that palaeoartistic depictions of certain animals make scientists imagine those animals in certain ways? This is actually a testable hypothesis and it’s something I’ll have to come back to at a later time.

Work in prep, pretty self explanatory. Credit: Darren Naish

My thinking at the moment is that palaeoart and the memes within it do not affect the views of working scientists, but (perhaps predictably) do have an impact on which hypotheses non-technical viewers recall and imagine to be reflections of reality. In fact, early results indicate that artistic depictions are substantially more influential than text for such viewers, an observation which (if valid) makes a mockery of the fact that some technical consultants consider artwork unimportant and beyond their remit.

The message from Witton et al. (2014). Credit: Witton et al. 2014

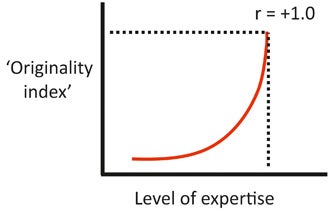

Originality in art correlates with expertise, here's a graph that proves it. Credit: Darren Naish

There’s much more that could be said about the nature of palaeoart memes, about the significance of palaeoart with respect to what it tells us about palaeontological history, about the interplay between palaeoart and science communication, and about the difference between innovators and experts in palaeoart versus generalists who produce art as part of the publishing industry. As usual, I remind you to support those who produce innovative content, do original research, and produce quality novel artwork (Witton et al. 2014). Palaeoart memes are not inherently bad so long as they don’t involve outright plagiarism, and they will persist as long as artists riff off the work of others.

And here’s a reminder that Popularising Palaeontology – the September 2016 seminar where this research was presented – has a great website where videos of the talks held at the event (including mine) can be seen: please go here.

For previous Tet Zoo articles relevant to the subjects covered or mentioned here, see...

Refs - -

Bartram, A. et al. 1975. The Prehistoric World. Grisewood & Dempsey, London.

Halstead, L. B. 1975. The Evolution and Ecology of the Dinosaurs. Peter Lowe, London.

Langston, W. 1978. The great pterosaur. Discovery 2 (3), 20-23.

Lull, R. S. 1919. The sauropod dinosaur Barosaurus Marsh. Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 6, 1-42.

Wetmore, A. 1930. The supposed plumage of the Eocene Diatryma. The Auk 47, 579-580.