This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Regular readers of Tet Zoo will know that I’ve written – on a great many occasions – about cryptozoology (the hunt for creatures known only from anecdotal evidence and not thought by the majority of scientists to truly await discovery as valid zoological entities). And I’ve written about various specific cryptids – the mystery beasts that are the alleged targets of cryptozoological investigations – on some number of occasions too.

Front cover of the hardcopy version of Hunting Monsters (Naish 2017).

But for all this, I’m surprised to find – even after more than 12 years of blogging – that there are a huge number of cryptozoological subjects that I haven’t ever covered at Tet Zoo at all. Purely because I’ve never actually said much about it before, I want to talk here about mokele-mbembe, the alleged ‘living sauropod’ of the Congo. This text is culled from the appropriate section of my 2017 book Hunting Monsters (a 2016 ebook version also exists) but is slightly modified and includes the references that couldn’t be cited in the book itself (Naish 2017). This brief article is not a definitive history of the mokele-mbembe and everything about it, but merely a part of the story.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

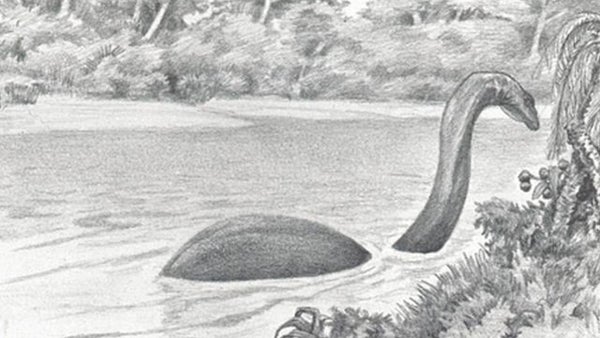

The classic idea of the mokele-mbembe: an aquatic, swamp-dwelling sauropod, as illustrated here by David Miller for Roy Mackal’s 1987 book on the subject. Mackal’s book also includes a version of mokele-mbembe reconstructed as a giant monitor lizard – an interesting speculation that I’ll have to cover in future. Credit: Mackal 1987

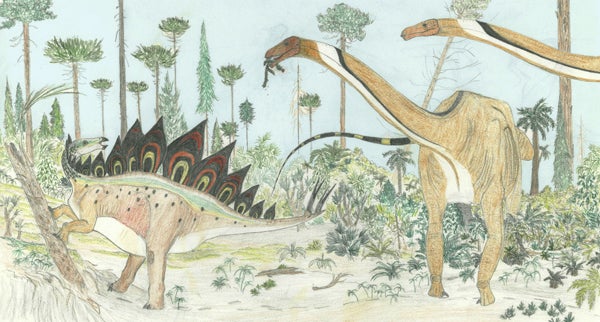

By far the best known of the alleged mystery beasts of tropical Africa is the mokele-mbembe of the Congo, an elephant-sized water beast, said to be a long-necked, long-tailed, herbivorous creature that lurks in deep forested swamps and forest-fringed lakes. It sounds very much like a sauropod dinosaur – or, more specifically, a mid 20th century, amphibious, fat-bodied, thick-limbed sauropod of the sort so prevalent in old, inaccurate artwork – and the notion that this is exactly what it is has been endorsed and discussed in many cryptozoological books and articles.

Front cover of one of the few non-creationist books written on mokele-mbembe (Mackal 1987). Credit: E. J. Brill

The idea that the Likouala-aux-Herbes region of the Republic of the Congo might be home to such a beast has been a popular, persistent one ever since the early 1900s. The great animal dealer and showman Carl Hagenbeck was among the first to promote the concept of living dinosaur-like reptiles in Africa, and his claim (made in his 1909 book Beasts and Men) immediately received global interest. It became a mainstream idea, publicised and promoted by ‘father of cryptozoology’ Bernard Heuvelmans and his followers from the 1950s onwards. Heuvelmans wrote a book on these creatures, published in French in 1978 as Les Derniers Dragons d’Afrique – and as yet not translated into English (though republished in 2003). Roy Mackal also wrote about them and his 1987 volume A Living Dinosaur? In Search of Mokele-Mbembe (which has a foreword by Heuvelmans) is a cryptozoological classic (Mackal 1987).

The cover of the republished edition of Bernard Heuvelmans’s Les Derniers Dragons d’Afrique, as yet untranslated into English. I love the cover-art produced for these volumes: the paintings are by Alika Lindbergh. Note the presence of the gargantuan snake and the pterosaur-like beast in addition to the sauropod. Credit: amazon

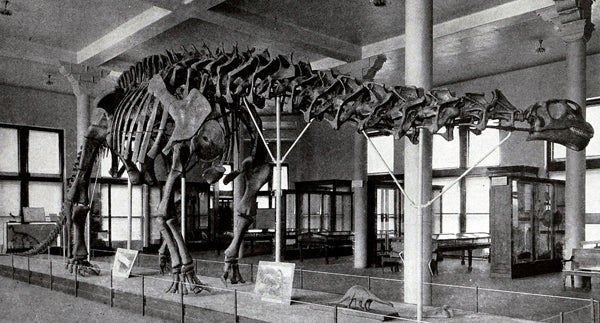

The cryptozoological perspective mostly holds that Hagenbeck’s stories originated in genuine eyewitness encounters with unknown animals. However, there’s an alternative cultural and sociological perspective. Hagenbeck was almost certainly taking advantage of an early 20th century dinosaur craze that was sweeping the globe at the time. Thanks to palaeontological discoveries made in the western interior of the United States during the late 1800s, the museums of the day were racing to obtain and install complete skeletons of Diplodocus, Brontosaurus, Apatosaurus and their relatives. Huge fanfare and public interest surrounded the display of these dinosaurs (Brinkman 2010), the very first of which were mounted in New York and London in 1905. Interest in fossil sauropods fuelled interest and excitement in living ones – hardly the first time that such a pattern of association had occurred (a claim has been made that the discovery of fossil plesiosaurs inspired sightings of long-necked sea monsters… an idea I’ll be coming back to soon), and hardly the last. It should be added that African legends and stories about giant monsters of course existed long before this time. However, none of the stories describe animals that sound much like sauropods.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, museums in Europe and North America underwent a ‘second Jurassic dinosaur rush’. Among the spoils of the time is this specimen at the American Museum of Natural History in New York (AMNH 460, a specimen long referred to Apatosaurus but currently of indeterminate status. Its skull is a mostly imaginary model). Credit: Public Domain, WikiMedia

What many proponents of the ‘living sauropod’ idea seem to have missed is that the half-rumoured notion of surviving African sauropods originally had nothing to do with the Congo region, but actually concerned Rhodesia – today known as Zimbabwe. Zambia, also in the far south of the continent, was said to be home to sauropod-like beasts during the early 1900s, as was the edge of the Sahara Desert and South Africa (Loxton & Prothero 2013).

A key sauropod specimen as goes the ‘second Jurassic dinosaur rush’ is the Carnegie Diplodocus, casts of which were sent around the world and to the great museums of London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Madrid, Bologna, Saint Petersburg, La Plata and elsewhere. This, of course, is the London specimen, which went on display in 1905 (albeit not in the main hall as shown here). Right now (June 2018), the specimen is currently touring the UK. Credit: Darren Naish

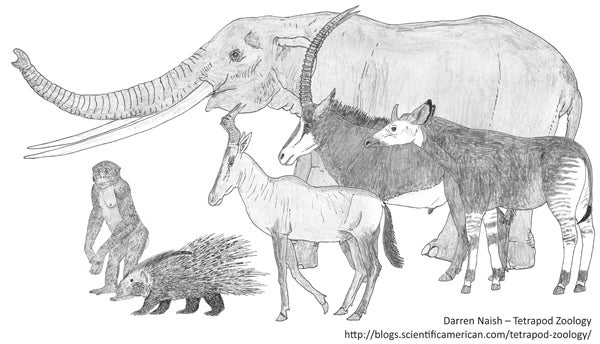

In effect, people latched on the idea that any wild region in Africa might be home to living relatives of Brontosaurus or Diplodocus. Sauropod-like monsters were not special denizens of the Congo region alone, but examples of a sort of lazy, naive view common in Europe and North America whereby all of Africa was imagined as a homogenous dark continent stuck in the Stone Age, inhabited wholly by spear-wielding jungle-dwellers, and where little had happened since the Mesozoic Era. Indeed, an oft-repeated phrase made in connection with the idea of surviving sauropods is that “Africa has scarcely changed since the time of the dinosaurs”. Even the most cursory examination of Africa’s fossil, geological or tectonic history will show that this is completely incorrect. Dynamic phases of mountain-building, continental rifting and desertification have had huge impacts on African animal life (e.g., Kingdon 1990), and numerous places in the continent have acted as so-called ‘species pumps’ – areas where high numbers of new species have evolved and from which they have dispersed. Such successful mammal lineages as elephants, humans, porcupine- and cavy-like rodents, and spiral-horned antelopes originated in Africa, often spreading out from the continent to colonise regions elsewhere. Even the great rainforests of central and western Africa have fluctuated massively in size and position, so much so that they were largely replaced by savannah during the last ice age (Malhi et al. 2013). Vertebrate species of rainforests are Cenozoic novelties, not Mesozoic relicts (Plana 2004). Disclaimer: there are tropical African arthropod groups – like tick beetles – that do indeed appear to be Mesozoic relicts (Murienne et al. 2013), but they’re tiny arthropods, not giant vertebrates. All of this makes a mockery of the idea – popular in the cryptozoological literature – that Africa has been a static, stable refugium for many millions of years, inhabited by unchanged animals of Mesozoic grade.

The African vertebrate fauna absolutely contradicts the idea that Africa's animal assemblage can be imagined as some sort of backwater, lost world or – to use current biogeographical terminology – ‘museum’ of lineages. These illustrations are from my in-prep volume on the vertebrate fossil record, on which go here. Credit: Darren Naish

In short, the concept of the mokele-mbembe as a living sauropod seems to have originated as a consequence of both a ‘dino-mania’ craze sweeping the world during the early 1900s, and of crass, erroneous stereotyping of African biological history – a view of Africa as somehow more ‘prehistoric’ than the rest of the world.

I don’t need to say that the mainstream view of the mokele-mbembe – that it’s an amphibious, fat-limbed, swamp-dwelling beast with multiple claws and distinct digits – is very obviously an exact mirror of inaccurate sauropod reconstructions as depicted in the late 1800s and across the early and middle decades of the 20th century. Today we know that sauropods were not like this. This scene shows the Morrison Formation diplodocoid Diplodocus, a Stegosaurus at left. This image was produced prior to the 1992 discovery of dorsal spines in diplodocoids. Credit: Darren Naish

For those disappointed with the fact that this article doesn’t evaluate the evidence that’s been put forward in support of the mokele-mbembe’s existed, the rest of the book’s chapter goes on to discuss that evidence (Naish 2017). I may revisit the subject of the mokele-mbembe in time...

For previous Tet Zoo articles on cryptozoology and Hunting Monsters, see...

Is Cryptozoology Good or Bad for Science? (review of Loxton & Prothero 2013)

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths

A Review of Neanderthal: The Strange Saga of the Minnesota Iceman, Part 1

A Review of Neanderthal: the Strange Saga of the Minnesota Iceman, Part 2

And for articles on actual sauropods, see...

Sauropod dinosaurs held their necks in high, raised postures

Gerhard Maier’s African Dinosaurs Unearthed: the Tendaguru Expeditions

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part I)

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part II)

Junk in the trunk: why sauropod dinosaurs did not possess trunks (redux, 2012)

Refs - -

Brinkman, P. 2010. The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kingdon, J. 1990. Island Africa: the Evolution of Africa’s Rare Animals and Plants. Collins, London.

Mackal, R. P. 1987. A Living Dinosaur? In Search of Mokele-Mbembe. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

Malhi, Y., Adu-Bredu, S., Asare, R. A., Lewis, S. L. & Mayaux, P. 2013. African rainforests: past, present and future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 368, 20120312.

Murienne, J., Benavides, L. R., Prendini, L., Hormiga, G. & Giribet, G. 2013. Forest refugia in Western and Central Africa as ‘museums’ of Mesozoic biodiversity. Biology Letters 9 (1), 20120932.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Plana V. 2004. Mechanisms and tempo of evolution in the African Guineo–Congolian rainforest. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 359, 1585-159410.