This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Five years ago the first baby boomers turned 65, their babyhood now nothing more than stories for grandchildren about duck-and-cover drills and The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show. Some 10,000 involuntary recruits from the immediate post-war generation join the ranks of senior citizens every day.

The formal beginning of late life is also when Alzheimer’s risk rises sharply. One in nine people 65 and over receive a diagnosis—a number that rises to one in three for those 85 and up. The statistics are fairly harrowing. More than five million patients currently suffer from the disease. One estimate tags the annual costs for dementias—of which Alzheimer’s is the most common—as probably exceeding those for heart disease or cancer.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Absent some intervention, the graying of America means that the number of U.S. afflicted could double in 20 years. The Aging Boom, which affects the whole species, not just those with U.S. passports, has been complemented by one drug failure after another, raising the question: Can Alzheimer’s be stopped? That query, in fact, is the title of a NOVA documentary scheduled to air on April 13 on PBS stations.

As do most documentaries about Alzheimer’s, this one begins by sketching out the magnitude of the challenge of making a difference for Alzheimer's patients. “It’s going to grow to epidemic proportions. It has the potential for bankrupting the entire medical system,” neurologist Ken Kosik tells NOVA. The personal anguish for both patients and caregivers are also chronicled. “Alzheimer’s is like having a sliver of your brain shaved off every day,” says one patient. (Watch an outtake from the NOVA episode about caregivers.)

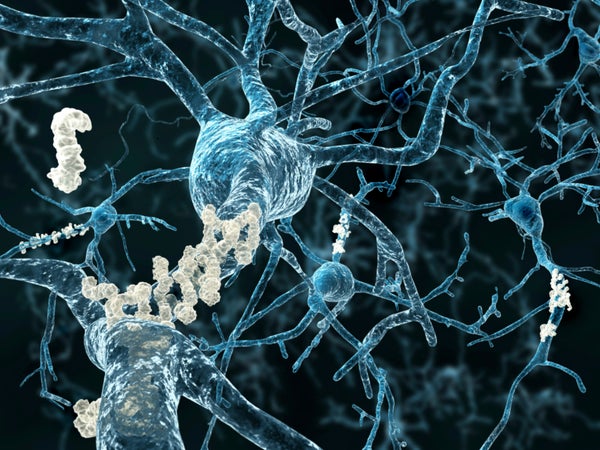

The program transcends accounts of personal tragedy by turning its focus to Alzheimer’s drug trials that are among the most innovative attempted for any disease. Advances in genetics, brain imaging and biotechnology now enable drug candidates for Alzheimer’s to be tested years before the first symptoms of memory loss appear. The challenge of a prevention trial requires monitoring side effects like brain swelling in an otherwise healthy patient and somehow figuring out if a drug is working in this cognitively normal individual. Large pharmaceutical companies are moving forward anyway because of the realization that disease progression—the buildup of cellular crud and the dying of brain cells—might be quite far along by the time a patient receives a diagnosis. Of course, they are also enticed by the potential for a blockbuster drug to top all blockbusters.

NOVA goes to Medellin, Colombia, to tell the story of a compassionate Colombian neurologist, Francisco Lopera, who discovered an extended family of more than 5,000 individuals in the city's environs that suffer disproportionately from Alzheimer’s. Working with Kosik and other researchers, Lopera helped pinpoint a dominant genetic mutation that can be traced back to a single Spanish conquistador.

The Colombian group was ideal for testing a prevention drug because the researchers knew that the disease would manifest, in most cases, just before a mutation carrier’s 50th birthday. Coupled with newfangled brain-imaging techniques that allow tracking of toxic brain proteins, a randomized clinical trial could be initiated 10 or 20 years before the pathology begins to see whether a drug removed cellular detritus and a patient did not go into a decline.

That is exactly what Genentech is doing in a trial under way there to remove the amyloid-beta peptide, which aggregates into plaques. The drug is being administered to trial participants in Colombia who are at least 30 years old and then amyloid levels and cognition are being closely monitored. (Scientific American has followed this story here and here—available for subscribers.)

Back in the U.S., other prevention trials are underway or in the planning stages. The Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, which is helping conduct the Colombian study, is preparing to launch a prevention trial in the U.S. for people with a genetic risk factor. But unlike the Colombian mutation, the genetic variant, APOE4, doesn’t guarantee that a person will become ill. Watch an outtake about this trial:

The NOVA episode acknowledges that an elixir to restore vanished memories is an improbable likelihood. But it also fails to break out of the well-worn TV template that requires the introduction of some initial tension at the beginning of the hour, framed by pulsing background music, that builds to a climactic finish. (Frederick Wiseman, we need you.) The documentary sticks to this predictable routine, but, it also recognizes that the ultimate denouement is likely be a messy affair. Another aberrant protein known as tau will probably need to be targeted as well as amyloid, particularly for patients who have already developed the disease—check out this outtake on tau:

In fact, the challenge presented by Alzheimer’s may be even tougher than depicted. Drugs against amyloid and tau might need mixing into a cocktail that also includes agents that protect neurons, quell inflammation and restore out-of-whack neural metabolism. Quibbles, aside, however, this NOVA episode is probably the best summation to date of where research for this mind-robbing illness is headed.