This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

I'm crying over a dang piece of machinery, but folks, this little rover was special.

Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity was meant to last 90 days; she survived for over 14 years. She was meant to show us less than a mile of Martian landscape: before the end, she traversed 28 miles of terrain and investigated many key geological features of the red planet.

Named by an immigrant girl, she embodied some of the best traits of America and humanity: our perseverance, our curiosity, our determination, our teamwork, and our joy in discovery.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

She was among the best (if not the best) robotic geologists of our solar system.

We'll be drawing on the data she provided for generations. If we ever successfully establish human communities on Mars, she will have been one of the explorers who made it possible. She made astrogeology a regular thing. She was unique, and she'll never be forgotten.

Perhaps, when humans finally make it to Mars personally, gentle hands will brush the dust from her solar panels, replace her worn components, and wake her from her slumber. Perhaps we'll let her rest. We may build a monument, or leave her to stand as her own memorial. But one thing is certain: we will never forget her.

Whether this is goodbye or merely goodnight for now, we can celebrate the life and work of this extraordinary little rover, and give our hearty thanks to the human team that kept her alive and exploring for so long.

Opportunity on Burns Cliff. Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech and Cornell

The Night NASA Said Goodbye to Oppy

Zurbuchen put it beautifully in his remarks to us that night: “Machines are a manifestation of teams.”

Humans built this robotic emissary and sent it to a world to which we ourselves cannot yet venture. It dutifully explored for over 50 times its expected life span. People were married, babies were born, lifelong friendships were forged, all over this rover. It carried many pieces of us with it on its journey on Mars, and those pieces will remain there with her and the dust.

The last phrase I heard as I began my descent out of The Darkroom was from an unidentified Opportunity team member: “13/10 would science again.”

When all good things that must end finally come to that end however, there is no denying the feelings that accompany such finalities. The MER team members, both present and past who were at the event, each of whom bonded with Spirit and Opportunity to one degree or another, in one way or another, wrestled with their emotions, and their good-byes.

“It’s hard at this point,” said Rover Planner Ashley Stroupe, who earned the distinction at JPL as the first woman driver on Mars. “It’s very fresh and I don’t know that I’ll ever have an experience that matches it. What I am feeling is that it’s just been such a privilege to go on this journey with these people and these rovers.”

The Sheer Distance Opportunity Roved Across Mars Still Has Us in Awe

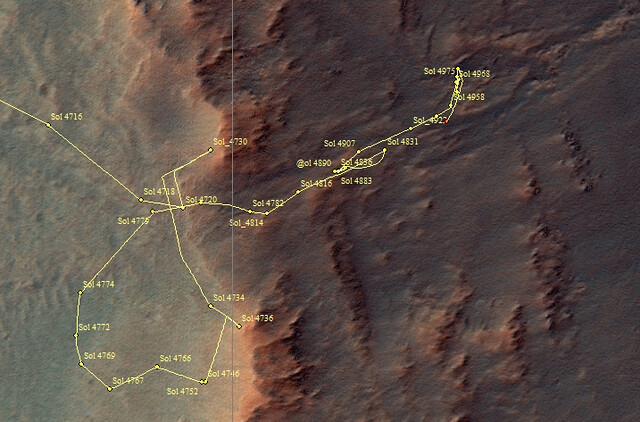

Detail of Opportunity's course. For the full image, click here. Credit: NASA

As we remember the now-officially-dead Opportunity rover this week, one fact keeps sticking out to me: That machine traveled a whopping 28 miles across the surface of another planet. And it did so in short, nerve-wracking spurts. Spread over the course of 14 years, 28 miles may not sound like that much, but consider the many obstacles Oppy faced—including an agonizing 38 days stuck spinning its wheels in a soft sand dune.

Opportunity traveled exactly 28.06 miles (45.16 kilometers) during its time on the Martian surface. That’s more than the distance traveled by the Apollo 17 lunar rover (22.2 miles), the Soviet Lunokhod 2 rover (24 miles), the Curiosity rover (12.3 miles), or Opportunity’s partner, the Spirit rover (4.8 miles). Along the way, it took images of vast planes, sandy dunes, and craters—and it found evidence of water on the Red Planet.

NASA’s Opportunity rover is dead. Here’s what it saw during its 14 years on Mars.

Opportunity (and Spirit) made some stunning discoveries, including the presence of gypsum, which is formed from mineral-rich water and suggests Mars’s surface once had much more water. It also discovered the mineral hematite on the surface, another sign the planet had a wetter past. Spirit found evidence (in the form of chemicals in rocks) that Mars’s atmosphere was once thicker, possibly indicating the planet used to be more hospitable to life.

Opportunity got an amazing perspective of the Martian surface, sending us back many incredible photos of its geology. It even spotted the Martian version of a solar eclipse, as the planet’s moons, Deimos and Phobos, traversed the sun.

Mars Exploration Rovers: Top Science Results

Near the rim of Endeavor Crater, Opportunity found bright-colored veins of gypsum in the rocks. These rocks likely formed when water flowed through underground fractures in the rocks, leaving calcium behind. A slam-dunk sign that Mars was once more hospitable to life than it is today!

11 of Opportunity's Most Impressive Scientific Triumphs

Astrum has a wonderful series of videos showcasing Opportunity's Mars field work: