This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

You and I enjoy cleaner air thanks to air pollution standards based on science. But now that could change. Last week, science advisors to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) drafted a letter criticizing the agency’s use of science to set ambient air pollutant standards. This is the latest development in the EPA’s process to update the health protective standards for particulate matter and ozone—the two air pollutants most responsible for early death and sickness in this country.

The letter, along with previous actions taken by EPA leadership and the agency’s clean air science advisors, raises alarm bells for anyone who understands the EPA's careful consideration of science in air pollution policy. These developments risk unraveling the methodical process that, for decades, has effectively ensured we have science-based air pollution standards and steady reductions in air pollution—and much of these actions aren’t making many headlines. Here's a rundown of recent changes to ambient air pollution standard updates and why all of this matters.

1. EPA leaders and CASAC are breaking with long-standing policy and practice that ensures science informs air pollution decision making.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

We must first look at how the process is supposed to work. National ambient air pollution standards set by EPA must be based on science and at a level that “protects public health with an adequate margin of safety.” This means the EPA must only consider the science that answers the question of what protects all people, including sensitive populations, such as the elderly, children, and those with lung and heart diseases. In assessing the science and the standards, the EPA relies on expert advice from the seven-member Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee, which has always been supplemented by a panel of additional experts on particular pollutants under review.

These experts publicly debate and review the agency’s science assessment, that is, the document that summarizes all the relevant science we have on a relationship between an air pollutant and its health and welfare impacts. This crucial document informs how the EPA thinks about the risks posed by setting the standard at different levels and what the impact of such a policy will be more broadly. (In EPA speak, the Integrated Science Assessment informs the Risk and Exposure Assessment and the Policy Assessment.)

CASAC, with help of the review panel, will then make an official recommendation for what level of air pollution will protect public health with an adequate margin of safety. Together these three documents, and CASAC’s recommendation, go to the EPA administrator who will ultimately set the standard. Thus, CASAC and the scientific assessment are essential because they inform this entire process and ensure that the EPA is basing policies on the best available science. This is why changes to the process matter.

Credit: Union of Concerned Scientists

2. The Trump Administration is cutting science out of air pollution policy.

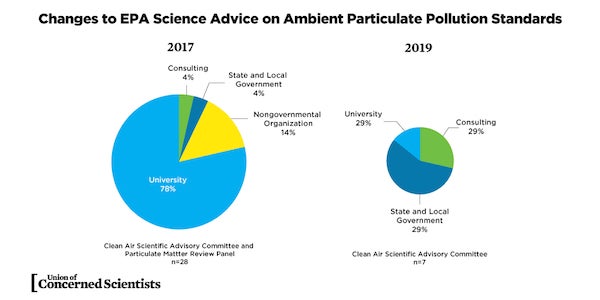

These challenges didn't start with this month's letter. Back in October the EPA nixed the particulate matter review panel and failed to convene an ozone panel. As explained above, these panels of experts are meant to supplement the expertise and perspectives of CASAC and have played a crucial role in informing air pollution standards since the first CASAC reviews in 1978. Also last October, EPA leadership announced an aggressive timeline that would complete reviews of both particulate matter and ozone by 2020. This the equivalent of lightning speed in the science policy world and meeting such a timeline will mean fewer public meetings and fewer opportunities for the public and experts to provide input. A faster timeline combined with a lack of pollutant panel to inform the standard means that far less science can inform the air pollution standard than has in the past.

Before all this, a memo from then-administrator Scott Pruitt laid the groundwork for cutting science from air pollution standard updates. We are now seeing those recommendations come to fruition.

3. EPA doesn’t have the science advice it needs.

Without a review panel, science advice is left to the seven-member CASAC. To be clear, no seven people, even if top experts, would have the breadth and depth of expertise needed to fully review the EPA’s science assessment. The beast of a document draws from diverse fields, from epidemiology to toxicology to clinical medicine to ecology. And this isn’t just my opinion, members of the current CASAC themselves, said in the draft letter that that they don’t have the needed expertise to conduct the review for particulate pollution.

On top of this hamstringing of the agency’s science advice, EPA already shook up its advisory committees. The agency kicked off its advisory committees anyone who had a current EPA grant. Paradoxically, EPA claimed this represented a conflict of interest, while scientists working directly for regulated industries did not. Following this new policy, the agency removed several independent experts from CASAC and replaced them with people from state and local regulatory agencies and chose a chairperson with fringe scientific views who consults for the American Petroleum Institute. The resulting committee is missing representatives from key scientific disciplines such as epidemiology. It is difficult to argue that this new CASAC represents the top independent experts the scientific community has to offer.

4. Members of a flawed committee recommend upending EPA’s approach to science.

The letter from CASAC chair Louis Anthony (Tony) Cox Jr released this month essentially trashes the EPA science assessment, inexplicably calling the lengthy, exhaustingly referenced document “unverifiable opinion” and claiming that fails to follow the scientific method. Dr. Cox calls for a brand new approach, asking the agency to throw away the long used and scientifically backed weight-of-the-evidence framework in order to determine the health effects of air pollution. It is hard to overstate just how jarring this is. With little explanation or scientific support, the CASAC Chair is suggesting overturning a framework that has been supported by 11 past CASAC committees and 138 top scientists.

Alarmingly, the committee could not come to consensus on a long-held scientific understanding: that fine particulate matter is linked to early death. Many thousands of studies in the past several decades have built evidence demonstrating this link. The fact that CASAC appears to be now renegotiating this long-held mainstream scientific understanding is breathtakingly backwards.

On March 28, CASAC will hold its next meeting to discuss the draft letter and the committee’s final recommendations on how EPA should finalize its science assessment. At this point, it is unclear what the committee will collectively decide, and whether they will have any consensus comments for the EPA. What is clear is that the EPA’s process for updating air pollution standards is changing in ways that threaten the agency’s very use of science to protect the public from air pollution. Regardless of what happens on March 28, and in this review process for particulate matter, we are witnessing this administration chip away at the foundation for air pollution protections in this country. And that puts us all at risk.