This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

It’s no news to those who follow science that the natural world is astoundingly beautiful—not just on the scale of our ordinary lives, but also in realms too far away or too tiny to be seen with our eyes alone. Artists have discovered this as well, and sometimes, the artists are themselves scientists.

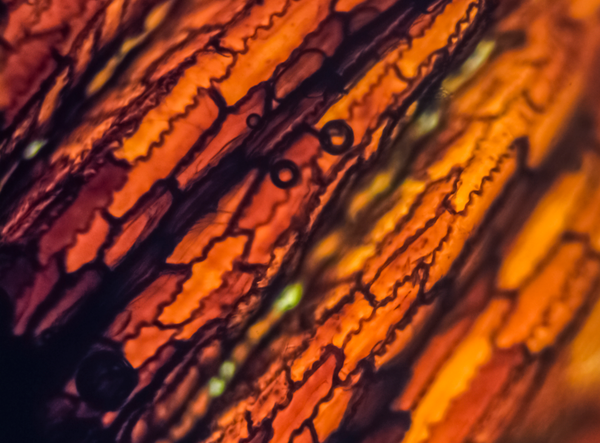

That’s certainly the case with Carrie Norin, an evolutionary biologist who teaches science at Princeton Day School, in New Jersey. Her photographs of the microscopic world reveal a spectacular universe of form and color we would never otherwise notice or have access to. They’re not simply striking to look at, however; they’re also proof that the invisible, relentless hand of evolution by natural selection is responsible for the seemingly infinite variety of life forms on our planet.

Credit: Carrie Norin

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Here’s how Norin puts it:

“Through my photography, I explore the interplay between two imperceptible worlds: the infinitesimal scale of cellular biology and the profoundly slow pace of biological evolution. These two worlds lie beyond the boundaries of observation, yet intersect harmoniously, shaping the form and function of all living things. This work aims to honor the evolutionary adaptations that have shaped the plant kingdom for hundreds of millions of years, while revealing their hidden beauty at the cellular level.”

And here’s how she described her process in an artist’s statement for a recent show:

“The initial process of selecting the samples involves exploring the fields and gardens at and around Princeton Day School, or the greenhouse on campus. I find particularly interesting specimens on the macro level and then see if they inspire me once under my microscope. Most often, they don't. Occasionally, however, I see something that immediately piques my interest.”

Norin prepares her specimens in various ways. Most are straight cross sections or peels, although some are whole plant parts, either lit from above on a stereoscope or, if they’re translucent enough, backlit on a light microscope. She’ll sometimes stain the material with particular chemicals that are absorbed by one type of molecule in order to differentiate tissue or highlight certain parts of the cellular structure.

None of this information, of course, is necessary to appreciate the pure beauty of Norin’s images.