This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

In my last piece, “The Neuroscience of Paid Parental Leave,” I discussed how infants’ attachment with their parents is critically involved in brain development. I described a bizarre paradox wherein physician trainee programs don’t provide trainees the types of leave recommended by their own organizations (like the American Academy of Pediatrics). In response, I received many supportive emails that helped me better understand the legal and economic aspects of paid parental leave. So I figured I’d share what I’ve learned by describing two experiments: a thought experiment of a well-intended but legally problematic parental leave policy and a state-wide economic experiment that California began in 2002.

Crafting non-equitable paid parental policies is a common mistake that well-intentioned employers make when they provide leave to their employees. Take, for example, an imaginary company called Luxet, which truthfully wants to support new parents. Luxet offers two weeks of paid leave to birth fathers while offering six weeks to adoptive fathers and six weeks to either adoptive or birth mothers. Because Luxet only offers birth fathers two weeks, its policy is not consistent with Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act, the standards set forth by the U.S. Supreme Court and the guidance of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Peter Romer-Friedman, an Equal Employment Opportunity Attorney in Washington, D.C., helped me understand that Title VII specifies that employers may provide birth mothers with a greater amount of paid parental leave than birth fathers so long as it is a medical leave meant to help the mother recover from pregnancy and childbirth, separating it from caregiving leave. Based on this rule, employers may not provide greater caregiving leave to mothers based on a stereotype that mothers, not fathers, ought to be the primary caregivers of their infants. (See Title VII, Enforcement Guidance: Pregnancy Discrimination and Related Issues, Section I.C.3).

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Because Luxet provides the same six weeks of paid parental leave to adoptive parents and to birth mothers, the policy indicates that paid leave given to birth mothers is really meant for caretaking, and not medical recovery from childbirth. In other words, the policy untethers the leave given to birth mothers from the need to recover from childbirth (even though, of course, birth mothers are recovering during this period). While Luxet provides birth mothers and adoptive parents six weeks of paid caretaking leave, Luxet provides only two weeks of paid caretaking leave to birth fathers. This disfavors birth fathers vis-à-vis birth mothers and adoptive parents who receive six weeks of caretaking leave. In other words, the only employees who receive just two weeks of paid caretaking leave are birth fathers, solely due to their gender. This is not equitable and, therefore, not consistent with Title VII.

Cynthia Calvert, a senior advisor for family responsibilities discrimination at WorkLife Law, helped me understand that if Luxet is an educational organization and receives federal financial assistance, Title IX of the Civil Rights Act further applies. Title IX not only prohibits discrimination based on sex, but it prohibits discrimination based on parental status. This further motivates a change in Luxet’s parental leave policy.

Of course, because the U.S. has no legislated paid parental leave policy, the fact that Luxet offers paid parental leave at all—in theory—reflects their social conscience and sense of goodwill towards their employees. After discovering that their generous paid parental leave policy doesn’t meet the requirements of the law, Luxet’s humanitarian sensibilities could chill and they could simply equalize caregiving leave by giving everyone nothing.

And this is why conceptualizing paid parental leave as an employer’s token of generosity is fundamentally flawed—frankly I don’t expect businesses to be generous. Generosity is too subjective to be predictable and much too nebulous to build policy around. Whether employers should provide paid parental leave should not be a moral, but rather an empirical question, one that demands empirical inquiry.

The question of whether parents should spend time bonding with their newborns was answered experimentally, through neuroscience and psychology. Likewise, the question of whether businesses and societies should provide paid parental leave is being answered experimentally, through an economic experiment in California.

The experiment began in 2002, when California passed the nation’s first comprehensive Paid Family Leave (PFL) program. The program provides six weeks of partial wage replacement for workers who go on leave to bond with a new biological, adopted, or foster child. The caregiving leave is equitable, meaning it is available to fathers as well as mothers during the first year after a child is born or placed with the family. Importantly for biological mothers, it is available in addition to medical leave offered for the purpose of recovering from childbirth and pregnancy. The six weeks of leave can be continuous or intermittent within this first year.

Importantly, the program is sensitive to and continually updated by usage data. For example, in 2017 the program provided 55 percent of earnings, up to $987 per week, However, in 2018, the wage replacement rate will increase to 60 percent for most taxpayers and workers who earn very low wages (i.e. near minimum) will receive 70% of their usual weekly wages.

According to Eileen Appelbaum, Senior Economist for the Center for Economic and Policy Research, there is significant data behind this change, “The program usage data show that low wage workers do not make use of the PFL program when needed because 55% of the minimum wage is not enough to live on. [The increase] is intended to address that problem—these families and their children are very much in need of time to bond, which is very important for the infant's development.”

The clever program is funded by an employee-paid, inflation-indexed payroll tax, meaning there are no direct costs to employers. And by building on California’s existing state disability insurance (SDI) system, the administrative burden doesn’t fall on businesses.

Five years into the program, the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C. surveyed 253 employers and 500 individuals who had participated in the program. Their goal was to answer (among other things) whether the program was a sound business practice and whether it improved employee retention and thus reduced business costs associated with recruiting and training new workers.

Here are some of their observations:

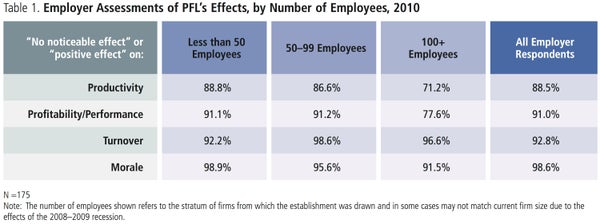

Employers reported that PFL had either a “positive effect” or “no noticeable effect” on productivity (89 percent), profitability/performance (91 percent), turnover (96 percent) and employee morale (99 percent). (See table below)

91 percent of employers stated that they were unaware of any instances of abuse of the program.

Small businesses were less likely than larger establishments (those with more than 100 employees) to report any negative effects.

About 60 percent of employers reported that they coordinated their own benefits with the state PFL program, leading to cost savings.

Credit: Table reproduced with permission from Ruth Milkman and Eileen Applebaum

These results suggest that paid parental leave provides an economic boon to businesses. California’s experiment showed that paid family leave generated cost savings for businesses, either due to reduced turnover or because they coordinated their own wage replacement benefits (such as paid sick days or vacation) with the program. Other states have since adopted similar policies including New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island and Washington. But say, for instance, that Luxet was based in Connecticut, the economic benefits of paid parental leave would still apply for highly skilled employees.

Highly skilled workers like the physicians I wrote about in my previous post are not a readily renewable resource, meaning that they are not easily replaced. Even physician trainees—whose position nears that of a temporary, contract worker—are not completely renewable because they may only be “hired” annually. In addition, a physician trainee (like any employee) becomes more valuable to a business each year, making them more costly to replace.

In fact, Stanford University recently reported that the cost of recruitment for each new physician—depending on the specialty and rank of faculty—ranges from more than $250,000 to almost $1 million. Far better economics to invest in the already developed human capital within the organization by providing benefits that help attract and retain skilled workers.

Further Resources

Free Articles:

“Leaves that Pay: Employer and Worker Experiences with Paid Family Leave in California.” An analysis of the first six years of California’s Paid Family Leave legislation, performed by the Center for Economic and Policy.

“Paid Family Leave Pays Off in California”, Eileen Appelbaum and Ruth Milkman discuss the Center for Economic and Policy’s results in the Harvard Business Review.

“Job Protection Isn’t Enough: Why America Needs Paid Parental Leave”, a report by the Center for Economic Policy and Research, December 2013. Research in Washington, D.C.

“The Pregnant Scholar,” provides information about the legal requirements of Title IX as they relate to pregnant, breastfeeding, and parental leave.

Books:

“All In”, by Josh Levs, a playbook (complete with sound, data-driven arguments) for parents trying to negotiate their own parental leave and for businesses trying to create better family-centered policies to attract and retain employees.

“Unfinished Business: Paid Family Leave in California and the Future of U.S. Work-Family Policy.” Ruth Milkman, Eileen Appelbaum. A fuller and slightly updated analysis of California’s Paid Parental Leave Program.