This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

My father has lab coats hanging in his closet. His basement is filled with beakers, flasks, and strangely-cut glassware of all different sizes. The house is lined with piles upon piles of journal papers, stacked like gold bricks at Fort Knox, on the shelves, against the walls, and finally for lack of space, down the stairwell. Growing up, I thought that these were just symbols of Dad-hood. Every father would have these things. It was only going to a friend’s houses that I finally uncovered the truth.

My father is a scientist.

It’s probably more apt to say a scientist happened to be my father because the science came first, and the fatherhood second—during six feet of snow in graduate school in chemistry at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne. Yes, I was a graduate school baby. I would enjoy asking my father, was I on purpose, or an accident, and he would say, of course you were an accident, and then he would let out one of his high-pitched bird laughs that would echo across the house, and over the years, as my friends would spend their time impersonating it. My father the scientist loves telling people the truth, especially when it’s shocking.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

My father spent his career as a polymer chemist. When I was just three years old, he would take me for walks around our suburban neighborhood. He would hold my small hand and a garbage bag in the other, picking up trash along the road. If everyone did this, we would have a clean planet, he said. Like we were picking flowers, we would stop and would explain each piece of trash to me. This straw is made of plastic. It’s a kind of polymer, a long chain of moleculars (his word for molecules). This nylon rope is also a polymer. They have hydrogen bonds that make them very strong.

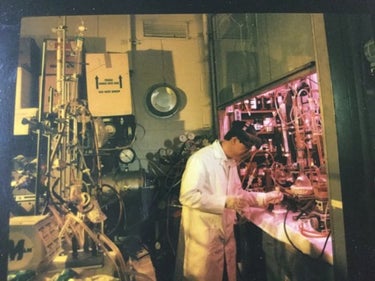

The author’s father, Dr. Henry Shun-Wun Hu, in 1986. Credit: Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, Laurel, Maryland.

We would walk home, his bag full of plastic, that he would recycle, or reuse, and my head full of new words. I wouldn’t really understand the meaning of these words for years, but seeing him say them made me feel as if there was a whole lot of knowledge out there. And seeing him so excited made me excited too, even though I had no idea what he was saying.

My father loved the outdoors and learning new things. In summers, he would take the family camping, involving three-hour road-trips to Allegany County in western Maryland. For most families, this is probably a somewhat staged event, with stays in a cabin or a tent, and observing nature from afar.

One day, we were driving in the minivan during one of the cabin trips, and father pointed out a deer that was lying on the side of the road. It was a common occurrence in the summer, but this time the deer was on a small deserted road rather than a busy highway. Let’s stop, he said. My mother shouted out, no way, we’re not going to stop, it’s too dangerous to stop by the road. But he was driving, so we stopped. My sister was 3 and I was 9, and we were both excited to take any chance to get out of the car.

We walked slowly up to the deer. There was not much blood, maybe just red around its lips, like a dab of lipstick. Its eyes were open and staring blankly, but otherwise the deer just appeared to be resting on its side, its legs spread. Its fur was shiny and lush. Then my father did it: he reached out his hand and petted the deer. My sister and I were horrified—there was no way we were going to touch something that big and dead.

It’s still warm, he said. It was as if he had been waiting for this opportunity for years. It was finally his chance to combine his two hobbies, eating venison at fine restaurants and collecting refuse at the side of the road. I couldn’t believe it was happening, but he ran to the van and started pushing our camping gear and coolers to the side.

Let’s bring it home, he said.

Now, my mother was really livid. We still had two hours left to drive to get home, and the car was full of camping gear, she said. This is totally crazy, or in Chinese, Ni feng Le—你疯了—a word that combines a strong wind with being sick. He nodded and continued moving things out of the car. My mother would continue to list all the logical reasons why this was a very bad idea—ticks, legal issues, the smell, what are we going to do with the deer when we get home—each interrupted with “You are so crazy!” My dad nodded his head, and continued to move things out of the car.

My parents would have many discussions like this, but ultimately, but when my dad’s curiosity was to be satisfied, he somehow always won.

Ultimately, the van was too crowded to put the deer in the trunk. So, it had to go in the back seat right next to my sister, like another member of our family. The deer sat inside a translucent tarp, making it look like it was encased in ice. Placement in that posture made its eyes bulge, and its tongue was now rolled out of its mouth. That day I also learned about the capacity of human lungs. For the entire two-hour car ride, my sister screamed her lungs off, tears pouring down her cheeks. The screams would get softer over time, as she forgot where she was. Then she took one look at those bulging eyes and the tongue, and the screams started again.

When we were home, my dad said we should wait till dark so the neighbors wouldn’t see. Like Leonardo’s secret dissections, my parents unloaded the deer into the garage and shut the door. We stayed up all night, cutting and skinning with kitchen implements. Having never seen meat outside the supermarket, it was an intense learning and sensory experience. There were a lot of organs in an animal I learned.

There were some errors too—my parents cut the intestines first and the entire place reeked like a port-a-potty in summer. But I remembered seeing my parents working as a team to lug the deer around and remove various parts. My parents never held hands or hugged, but seeing them grunting as they each dragged the deer’s hind legs, well that is still one of the most romantic things I’ve seen.

By the time I was in elementary school, I still didn’t know much, but living with my dad had taught me some basic things about science. Scientists know a lot of things. They are always curious. They know when to be logical and when to follow a hunch. And they’re always, always teaching others. Oh, and one more thing.

Every once in a while, I would ask my mom, why do you love dad so much? She would smile, and say, Oh … it’s because … he’s so crazy.

He’s a crazy scientist, I thought.

Happy Father’s Day to all the scientists out there, and to all the dads who will be inadvertently teaching their kids things this summer.