This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

By now, you’ve seen it going around social media (as well as the Washington Post): Isaac Newton flourished during an outbreak of the plague. With Cambridge University shuttered, Newton retreated to his family home in Lincolnshire, where, in a remarkable burst of creativity, he laid the groundwork for his theories of gravity and optics, and invented calculus.

And it’s not just Newton: William Shakespeare, we’re told, wrote some of his best poems and plays while plague forced a closure of London’s theatres. Perhaps few of us will reach Newtonian or Shakespearean heights, but a recent headline in Psychology Today suggested that we not let this “free time” go to waste: “Coronavirus Confinement Can Help Educators Advance Careers.”)

Let’s take a closer look at what these two poster children for plague productivity achieved, beginning with Newton. As Richard Westfall notes in his biography Never at Rest, the plague indeed hit Cambridge in the summer of 1665, and Newton, who had just completed his B.A., returned to Woolsthorpe Manor, over 50 miles to the north. He remained there for a year and a half, and, apparently, the creative juices flowed; the period is often referred to as his annus mirabilis (“remarkable year”). As Newton would later tell one of his early biographers: “For in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention & minded Mathematicks & Philosophy more than at any time since.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Perhaps Newton’s greatest insight during this period was the development of the inverse-square law of gravitation, an idea that supposedly came to him as he compared the fall of an apple to the motion of the moon in its orbit. Like so many myths, the apple story appears to have a kernel of truth; there really was an apple tree beside the manor house (and one of its descendants still thrives). And, as Westfall notes, Newton told some version of the story to several different people (though he did so only late in life). At any rate, this insight was just a starting point; he was just beginning to understand gravitational attraction, and to discern its universality. As well, Newton appears to have been focusing intently on mathematics and physics before his period of isolation, and continued to do so afterward; his creative explosion spread well beyond his plague-cation, as it were.

And what of Shakespeare? Plague was a near-constant presence in the England of Elizabeth I and her successor, James I. When the death toll exceeded 30 per week, London’s theatres were ordered to close, forcing theatrical troupes to take a break or perform in the country. When a particularly nasty outbreak struck in 1606, Shakespeare used his time well, penning King Lear,Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra. Then, as now, Londoners were instructed to practice a version of social distancing. As James Shapiro writes in 1606: Shakespeare and the Year of Lear, no more than six people could attend a funeral, including the pallbearers and minister, “though these and other rules were often ignored.”

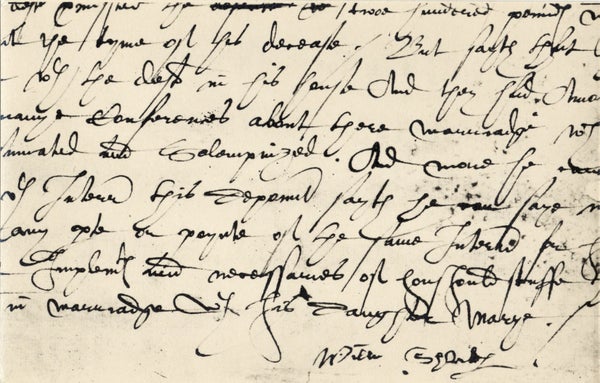

Those who tended to the sick had to carry a rod or wand, to make sure other Londoners gave them a wide berth. When an earlier outbreak closed the theatres in 1593, Shakespeare wrote the poem Venus and Adonis. (An article in Mental Floss helpfully notes that painter Edvard Munch, playwright Thomas Nashe and poet Giovanni Boccaccio were also remarkably productive during pandemics.)

By the middle of this month, the Shakespeare-Lear item had caught the attention of musician Rosanne Cash. But her tweet was soon followed by a backlash. A reply later that day: “Fair point, but I’ll bet he had childcare.” (In fact, Shakespeare’s wife and children were some 80 miles away in Stratford-upon-Avon.) Another respondent said that King Lear was all very well, but he would settle for playing Mario Kart. Yet another Twitter user reminded us that “Shakespeare wrote pretty much everything during the plague” including “the really boring parts of Titus Andronicus.” A Web site called Literary Hub summed it up: “So Shakespeare wrote King Lear during a plague. Well, good for him, say all the writers.”

As many have by now observed, the “opportunity” that working from home offers is far from egalitarian; for starters, it privileges those who don’t have children running underfoot. Unlike Shakespeare, Newton was childless (and possibly a virgin); and it seems unlikely that he pitched in with the cooking and cleaning at Woolsthorpe. (Newton was raised by his mother and her second husband; they were not exactly wealthy, but they did have servants.) As one Twitter user remarked: “The next person who tweets about how productive Isaac Newton was while working from home gets my three-year-old posted to them.” The tweet included a photo of her (let’s assume delightful) young child. Another user noted, “Isaac Newton didn't have Netflix or Nintendo at home.”

The bizarre expectation that one needs to be hyperproductive when under the equivalent of house arrest has rightly triggered pushback. Nick Martin, writing in the New Republic, hits the nail on the head: Believing that each waking hour must be a productive one “is the natural endpoint of America’s hustle culture—the idea that every nanosecond of our lives must be commodified and pointed toward profit and self-improvement.”

At the very least, it places grotesquely unrealistic expectations on those who are already grappling with far-from-normal working conditions. And secondly, it is just possible that Newton and Shakespeare were creative outliers, and that we mortals need not be ashamed of our lesser levels of achievement.

So please: Look after yourself, and those around you. You don’t have to learn a new language, master a musical instrument, write a screenplay or discover the Theory of Everything. Just getting through what lies ahead is enough.