This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

As visual beings, we perceive color and light without even a thought as to all the information we glean from it. Try to talk a toddler into believing the tiny airplane they see overhead is actually bigger than a house and you can get a glimpse into how our brains use what we have learned about our world to interpret what we see. But an estimated 285 million visually impaired people are not using this same information to perceive the world around them, and for those who never had sight to begin with, their understanding of the world develops quite differently.

Straw Boat by Ann Cunningham, 2016; 24” x 30" x 3/4”; slate. Credit: Ann Cunningham

In July, sculptor Ann Cunningham teamed up with the National Federation of the Blind (NFB) at their annual convention to create an exhibit of artwork created for or by blind people. Rather than being shooed away for getting too close to the art, attendees touched every curve and contour of these pieces by design.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Detail of Sequence, an exploration of one rabbit's hop by Ann Cunningham, 2015; 13.5”x 48"x 3/4"; carved slate. Credit: Ann Cunningham

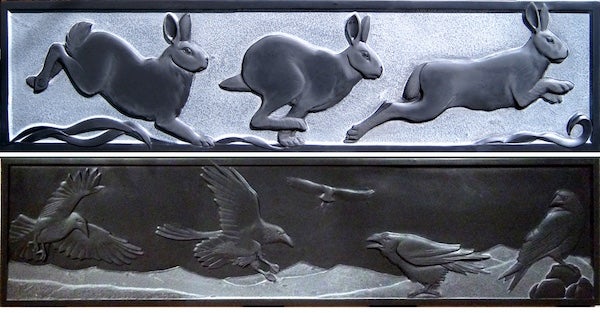

According to Cunningham, art perceived through touch conveys very different information than viewing a piece does. For example, these sequential images often animate in people’s minds when experienced tactually.

Top: Sequence by Ann Cunningham, 2015; 13.5" x 48" x 3/4”; carved slate. Bottom: On the Divide by Ann Cunningham, 2015; 22" x 7' x 3/4"; carved black slate. Credit: Ann Cunningham

In addition to experiencing a sensation of animation, Cunningham notes that people often also perceive much more volume than is actually in a sculpture. These wolves, when explored with a hand on each side of one animal, consistently give the impression they are much broader than their 3/4” thickness.

Wolf Pack #1 by Ann Cunningham, 2015; each wolf measures 12” x 18" x 3/4”; slate. Credit: Ann Cunningham

Though Ann Cunningham has normal vision, most of the 10 exhibitors in the NFB’s tactile art show are blind. Yolanda Thompson is one such artist. Born blind, she has been exploring stone.

Angels of Life by Yolanda Thompson, 2016; alabaster. Credit: Yolanda Thompson

In a world that is assessed through shape and form rather than light and color, large art is rarely more impressive or effective than what fits in the palm of your hand. Thompson’s sculptures reflect this; though small in stature, they offer an open and inviting window into a perspective formed without sight.

Ancient One by Yolanda Thompson, 2016; alabaster with macaw and parrot feathers. Credit: Yolanda Thompson