This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

I can’t help but feel a little bit sorry for Synoplotherium. Every time I’ve gone to visit the old beast, safeguarded behind a pane of glass at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, I’ve been the only one present to pay my respects to this enigmatic mammal.

As in any museum they inhabit, dinosaurs steal the show at the Peabody. The skeleton of O.C. Marsh’s great Apatosaurus – or is that Brontosaurus now? – leads a parade of tail-dragging saurians who show the osteological frames that artist Rudolph Zallinger used to paint the stunning Age of Reptiles mural that runs the length of the room. Yet, despite their celebrity, dinosaurs didn’t lead the way in introducing Peabody visitors to the past. The all-but-forgotten Synoplotherium has that honor.

The skeleton was found in the 45-million-year-old Eocene rock of Wyoming’s Bridger Basin, dug up by field workers Sam Smith and Jacob Heisey in 1875. It was one of the most complete fossil mammals yet found, and Marsh dubbed the species Dromocyonvorax for its dog-like appearance and the voracious appetite it must have had. Only after decades of osteological scrutiny did other researchers realize that Marsh’s “Dromocyon” was really a more complete representative of Synoplotherium – a title dubbed by Marsh’s nemesis E.D. Cope.

Marsh would have been furious at the name change, and he would have been aghast to see it on exhibit. Marsh fervently believed that bones were for experts only and any attempt at public display hindered research. Reconstructions should only be done on paper, never with real bones. It’s clear that not everyone agreed with this view, though, as the Peabody’s paleontologists went about mounting the bones of Synoplotherium almost immediately after Marsh’s death in 1899. Synoplotherium was the first creature to ever be mounted at the Peabody.

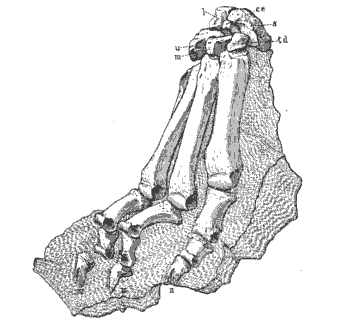

The right front foot of Synoplotherium, still in rock. From Wortman, 1902.

The skeleton hasn’t budged a bone since it was put back together in 1899. Each part of the German shepherd-sized carnivore creates the impression of an animal that is like a dog, but not quite. The tail’s too long, the skull’s too big, and the feet end in flat, blunted toes rather than claws. Now you might understand why paleontologists sometimes call Synoplotherium and its relatives – known as mesonychids – “wolves with hooves.”

Were Synoplotherium a dinosaur, there’d probably be an expansive literature on the Cenozoic flesh-ripper. It was the apex predator of a time when mammalian evolution took some decidedly strange turns, or at least what we’d consider odd with our 45 million years of hindsight. Things as they are, however, Synoplotherium is much like Patriofelis and other Eocene oddities – they have been named, categorized, and reconstructed, but not understood.

The first and last major source of information on Synoplotherium is a section of a massive review of Eocene mammals laid out by paleontologist Jacob Wortman in 1902. He covered the whole animal from its oversized skull to what remained of its tail, detecting a few surprises along the way. “The lower jaw of the individual under consideration is of unusual pathological interest, as showing, among these ancient animals, the result of healing of a fracture,” Wortman wrote. This Synoplotherium not only had the left side of its jaw cracked right at the midpoint, but survived the ordeal to old age, as shown by its worn-down teeth.

What broke the carnivore’s jaw? No one knows. Paleontologist G.R. Weiland commented that the break “was doubtless received in some raid on the young of Palaeosyops” – one of the rhino-like brontotheres – but this was just offhand speculation. It’s just one of countless mysteries that still surround the animal. I pulled the tomes Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America and The Beginning of the Age of Mammals off my shelf when I got home from my last visit to the Peabody, hoping for more, but compendiums didn't offer much detail beyond dental formulae and the impression that Synoplotherium was more of a runner than other mesonychids. Even among experts, this beast has been neglected.

Still, the bones remain. Their display cocoon makes study difficult – Marsh wasn’t totally off-base – but they still stand there, waiting to spill their stories. Clues about how Synoplotherium moved, ate, healed, and more are all patiently waiting, ready to show us a little more about a mammalian dawn when life was simultaneously familiar and strange. Go see for yourself, if you can, and wait a moment in the dim quiet for the beast to speak to you.

References:

Wallace, D. 2004. Beasts of Eden. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. xviii-xxi

Wortman, J. 1902. Studies of Eocene Mammalia in the Mash collection, Peabody Museum. Part I. Carnivora. The American Journal of Science.