This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Bear dogs are just about what you’d expect from the name. These extinct carnivores combined traits of both bears and dogs while not falling within either familiar group, burly runners whose skeletons seem to take on a threatening presence when museum shadows fall across them just right. Their skulls, in particular, speak to their predatory prowess, with flaring cheekbones where powerful jaw muscles were threaded and canine teeth that leave no mystery what they were used for. But it’s one thing to look at a skeleton and feel the intimidation of osteology. It’s another to figure out how all those parts worked in life, and that’s just what paleontologist Gemo Siliceo and colleagues did with western Europe’s last bear dog.

Experts know the animal as Magericyon anceps. It’s a new addition to the bear dog family – technically known as amphicyonids – as it was only officially named in 2008. Nevertheless, it’s already one of the best-known bear dogs, represented by the remains of over 13 specimens excavated from an approximately 8 million year old predator trap in Madrid, Spain. And from this exquisite sample, Siliceo and coauthors set about determining how this bear dog’s neck played into its killing capabilities.

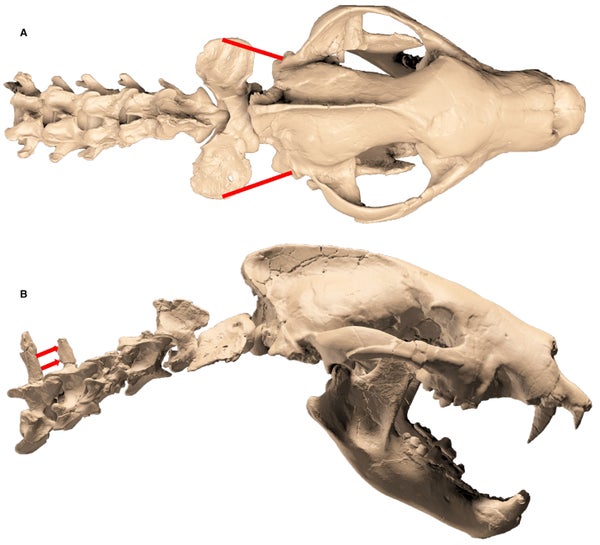

When we think of carnivores, our focus is naturally on the teeth and jaws. These are the points of contact between predator and prey. But it’s not as if these animals were disembodied, snapping jaws. The rest of the body matters, too, particularly the neck. “The cervical region functions in the support and control of the movements of the neck and head,” the researchers write, “actions important in prey capture and consumption.” To that end, Siliceo and colleagues scanned and modeled the skull and six neck vertebrae of Magericyon to reconstruct the bear dog’s musculature and put the predator through its virtual paces.

A reconstructed model of Magericyon. Credit: Siliceo et al. 2017

In their analysis, the paleontologists found that Magericyon was especially adept at side-to-side movements and rotation of the head. On top of that, the bear dog's cervical vertebrae supported strong muscles that would have helped stabilize the neck. Combined with other anatomical features, such as teeth suited to a hypercarnivorous diet and strong arms, a predatory picture starts to emerge.

Siliceo and coauthors suggest that Magericyon was an ambush hunter, tackling prey with muscular forelimbs before using those strong neck muscles to stabilize the head and jaws for a deadly killing bite. Those same neck muscles would have helped the bear dog tear flesh from carcasses, which the paleontologists expect the carnivore had to do quickly.

The same deposits that yielded Magericyon have also turned up hyenas, sabercats, mustelids, a bear, and other carnivores. Even though the bear dog was big – weighing over 200 pounds – some of the leopard-sized cats were sizable enough to act as kleptoparasities, stealing the bear dog’s meals. Such confrontations were probably rare. The predators of the time likely avoided each other rather than constantly clawing at each other’s throats, the researchers propose. All the same, Siliceo and colleagues write, “the efficiency of the killing abilities and prey consumption of this amphicyonid would have been an advantage,” allowing Magericyon to enjoy a bit of fast food before being harassed by other predators.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Reference:

Siliceo, G., Salesa, M., Antón, M, Peigné, S., Morales, J. 2017. Functional anatomy of the cervical region in the Late Miocene amphicyonid Magericyon anceps (Carnivora, Amphicyonidae): implications for its feeding behavior. Palaeontology. doi: 10.1111/pala.12286