This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Allosaurus, Tyrannosaurus, Giganotosaurus, Carnotaurus, and more. Most every dinosaur fan of any age can rattle off a list of the most imposing flesh-rippers of the Mesozoic, not least of all because they are often the stars of saurian cinema. Many hold soft spots for the likes of plant-chewers like Parasaurolophus and Brontosaurus, too, but, just as lions are more emblematic of qualities we admire than zebras, carnivorous dinosaurs always outstrip their competition. But what about the earliest predatory dinosaurs that chomped their way through the Triassic world long before our favorite giants? A stunning fossil found in southern Brazil adds some new wrinkles to the story.

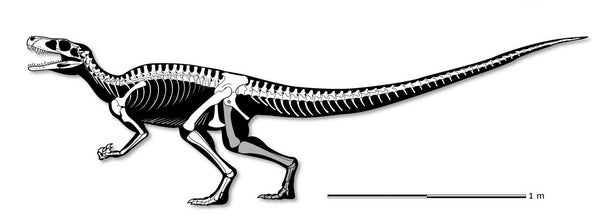

Paleontologist Cristian Pacheco and colleagues have named the dinosaur Gnathovorax cabreirai. If you know a bit of Greek and Latin, the genus name itself stands out as superlative. The title roughly translates to “jaw that is inclined to devour.” The fossil itself justifies the hype. This dinosaur, the researchers note, is a herrerasaurid – an early form of carnivorous dinosaur that’s mostly known from fragmentary remains of other species that are composited together in order to visualize the entire animal. Gnathovorax offers a more complete look at a single individual, and helps make sense of finds made elsewhere.

Around 233 million years ago, during the Triassic time Gnathovorax was roaming what’s now southern Brazil, there were no giant predatory dinosaurs. The biggest known were only about a sixth the length of their distant and much later relative Tyrannosaurus. All the same, dinosaurs like Gnathovorax were about as big as predatory dinosaurs of the time got, and these carnivores set the stage for what would come later. In fact, in this particular case the mostly-articulated skeleton of the dinosaur was found surrounded by the bones of species it might have preyed upon prior to its unintended contribution to the fossil record. The bones of Gnathovorax are framed by the scattered bones of weasel-like protomammals called cynodonts and tubby, beaked reptiles called rhynchosaurs.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

What makes Gnathovorax significant, though, is not so much its arsenal of sharp parts but the fact that the dinosaur offers a more comprehensive set of traits to compare with other dinosaurs. In recent years, as different experts and paleo programs have looked at the dinosaurs of the Triassic, there’s been disagreement about where some of the characters fit in the evolutionary drama. Herrerasaurids were considered early theropod dinosaurs, then possibly not dinosaurs at all, then perhaps relatives of the long-necked sauropodomorphs, or maybe as their own group of carnivorous dinosaurs that evolved alongside theropods before eventually vanishing. Drawing from the details of the new skeleton, Pacheco and colleagues consider Gnathovorax and its relatives as early members of the major saurischian family – part of the group containing theropods and sauropodomorphs, but distinct from either subset.

The analysis also adds more fuel to the debate of who might, and who might not, belong to the early dinosaur family. Papers have gone back and forth over the identity of lanky Triassic animals called silesaurids. Some analyses find them as a specific group of protodinosaur, relevant to the origin of all dinosaurs, and others cast them as early ornithischians – the beginnings of a family that would eventually include the likes of armored, horned, and shovel-beaked dinosaurs. Future studies will likely shuffle the tree around further, but, turning back to Gnathovorax, the dinosaur helps elaborate on the ecological context of dinosaur evolution.

There’s little doubt that Gnathovorax and its relatives were faunivorous. A mouth of recurved teeth leaves little doubt that these dinosaurs often, if not primarily, ate flesh, and they share a basic body type of predatory dinosaurs through time. And during the Late Triassic, their primary competitors for prey were not theropods, but early sauropodomorphs that were diversifying from carnivorous ancestors to more omnivorous forms, and eventually a reliance on plants. In the course of time, however, theropods took over the carnivorous niche and sauropodomorphs shaded more towards herbivory, while dinosaurs like Gnathovorax went extinct. It’s not clear whether these shifts were due to competition, or if theropods had the good luck to see their competition disappear, but it appears that the earliest dinosaurian terrors of the Triassic were not the first theropods, but groups that don’t have as much cultural cachet. Something changed during the Late Triassic time, making Gnathovorax a symbol of what’s yet to be discovered.