This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Pterosaurs are often treated like Mesozoic window dressing. They thrived alongside our favorite dinosaurs, holding the title of the first vertebrates to achieve powered flight, but are often spoken of as examples of “not dinosaurs” – their identity still defined by their evolutionary cousins. But, as pterosaur popularizers such as paleontologist Mark Witton have demonstrated, taking a pterosaur’s eye-view of the ancient world offers a deeper perspective of life through the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous. A newly-named pterosaur from Spain, for example, helps connect the geographical dots between pterosaurs across the northern hemisphere.

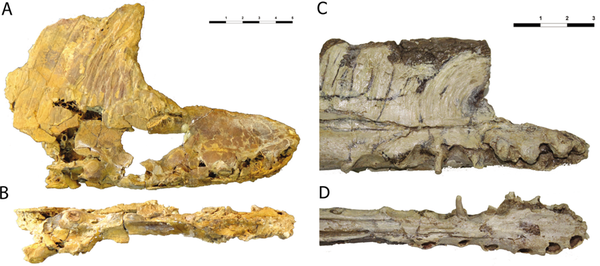

Paleontologist Borja Holgado and colleagues have named the Early Cretaceous flierIberodactylus andreui. Not much of the pterosaur is known so far, but the snout and crest collected so far indicate that this flying reptile is new to science. More than that, the anatomy of the roughly 125 million-year-old snoot bears a striking resemblance to that of another pterosaur found thousands of miles away.

The crested, toothy jaw of Iberodactylus looks very similar to that of the 120 million-year-old Hamipterus tianshanensis, Holgado and coauthors note. In fact, as it stands now, the two pterosaurs seem to be each other’s closest relatives. This is a little strange. Iberodactylus belongs to a group of pterosaurs called anhanguerians. Other pterosaurs from this group have been found on the Iberian Peninsula before, but Iberodactylus is more closely related to Hamipterus from China than any of the local species.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Paleontologists have seen this pattern before. Holgado and colleagues point out that various other Early Cretaceous animals found on the Iberian Peninsula – including sauropod dinosaurs, mammals, and crocodiles – seem more closely-related to species from eastern Asia than Europe. The evolutionary outline, in its current form, indicates that eastern Laurasia was the center of origin for various Early Cretaceous animals that then spread outward through the continent. As a family, these crested, toothy anhanguerian pterosaurs were hit, spreading worldwide after their appearance on the global stage.

Figuring out who originated where and when is about more than getting our artistic depictions of lost worlds just right. These connections also give paleontologists hints about where to look for future finds, or what specimens to take another gander at. Each linkage helps weave the broader evolutionary network that every fossil discovery is ultimately a part of. Finding another pterosaur isn’t just adding another name to the rolls. It’s part of piecing together how our world has changed over wonderful, incomprehensible time.