This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

A few weeks ago, one of my wife’s friends told me I need to write another children’s book. Not because I have a particular talent for it, but because her son has read and re-read Prehistoric Predators – illustrated by the amazing Julius Csotonyi – so many times that they need some new material.

I asked what sort of book her son would like, if I were to write a sequel. The reply: something like an encyclopedia, cramming in as many dinosaurs as possible into one volume with all their vital stats at hand. I used to love those books when I was about the same age. I didn’t really care about narrative. I wanted more dinosaurs, complete with the details of where they lived, how big they got, and what they ate.

But dinosaurs are squishy creatures. Most species aren’t known from anything close to even a single complete skeleton, so we’re left to estimate lengths and weights. And while we know plenty of places were dinosaurs died, where those animals actually lived – as in their home ranges and preferred habitats – is often only known in outline. And then there’s diet.

We can paint in broad strokes based on tooth shape and other details, but in terms of what any individual dinosaur – or even species – consumed, we have to hope for gut contents and petrified poop. And when paleontologists look to those dietary clues, dinosaurs don’t conform to the blunt divisions of carnivore, omnivore, and herbivore we’d like to draw.

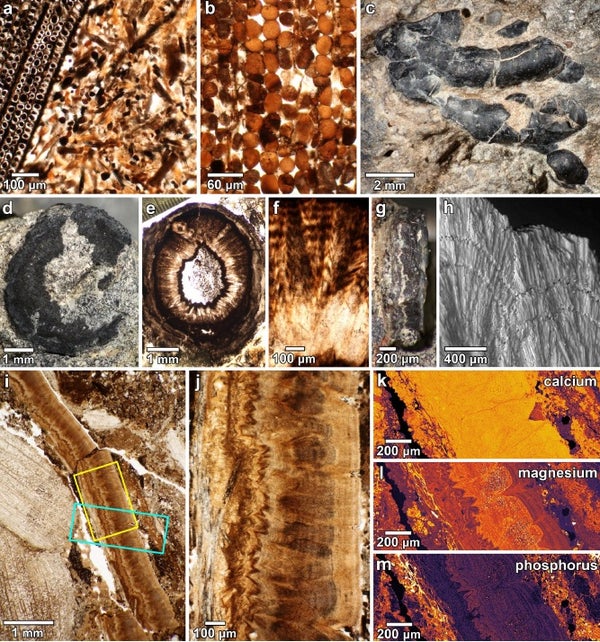

Contents of herbivorous dinosaur coprolites with crustacean parts inside. Credit: Chin et al 2017

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

This isn’t a new point, of course. Right at the top of a new paper on dinosaur dung excavated from southern Utah’s Kaiparowits Formation, paleontologist Karen Chin and colleagues note that feeding habits inferred from teeth need to be checking against more direct evidence. And in this particular case, the roughly 75 million year old feces of herbivorous dinosaurs contained some surprising foodstuffs.

Precisely which species of dinosaur left the prehistoric plops is unknown. But the shape and material inside indicate that these were what paleontologists would broadly categorize as large herbivorous dinosaurs – animals like the hadrosaur Gryposaurus or horned dinosaur Utahceratops. Thin sections of the fossils revealed that the coprolites are mostly made of fibrous conifer wood, with traces of fungal growth that the dinosaurs inadvertently ingested as they crunched through rotting logs. But there was something else. Inside some of the examined coprolites were bits of shell.

The shell pieces weren’t easy to interpret. After all, they’re the mashed up remains of meals enjoyed back in the Cretaceous. But Chin and colleagues were able to determine that the shell pieces were from crustaceans. (Mollusk shell material was also found, but, the researchers note, these were probably from gastropods that were consuming the feces before burial.) This wasn’t a one-off. Ten out of fifteen examined coprolites from several layers of deposition contained chewed-up crustaceans bits.

How did this happen? Chin and colleagues offer three scenarios. The dinosaurs could have actively and intentionally eaten the crustaceans – most likely freshwater crabs – as they stomped around. Then again, perhaps the crustaceans were in the rotting the logs the dinosaurs were feeding on, and therefore were either eaten because they were there or accidentally ingested. On the balance of the available evidence, though, Chin and coauthors propose that the dinosaurs were intentionally eating the animal prey – this was a persistent trend through time in the area, and the crustaceans are too large compared to dinosaur mouth size to just be accidental meals.

“The diet represented by the Kaiparowits coprolites would have provided a woody stew of plant, fungal, and invertebrate tissues,” Chin and colleagues write. This is more than just documentation of what dinosaurs in a particular place and time consumed. It’s a reminder that animals are flexible and have a wider array of behavioral and dietary options available to them than we might first suspect. Some herbivorous dinosaurs ate small animals, and I wouldn’t be shocked if someone finds a coprolite from a primarily carnivorous dinosaur with partially-digested plant material inside. The reason dinosaurs keep getting stranger is because real animals will always defy our expectations.

This post was supported by my generous backers on Patreon. For details on how you can get an early view of new blog posts and exclusive natural history essays, click here.

Reference:

Chin, K., Feldmann, R., Tashman, J. 2017. Consumption of crustaceans by megaherbivorous dinosaurs: dietary flexibility and dinosaur life history strategies. Scientific Reports. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11538-w