This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In 2001, while digging in the 1.3 million year old sediment of the archeological site Fuenta Nueva-3 in southeastern Spain, researchers began to uncover the bones of a mammoth. Some of the skeleton was in place. The spine, pelvis, and a few ribs remained connected. Other pieces, like the scapula and mandible, had been torn away, and all of the ancient elephant's limbs were missing. By itself, this wouldn't have been especially remarkable. Bodies fall apart after death. But it's what the excavators found surrounding the body that made this elephant special.

In the course of excavating the mammoth, researchers found 34 coprolites and 17 remnants of stone tools. This placed two different scavengers in this one place. The fossil feces belonged to Pachycrocuta. Think of a 240 pound spotted hyena with a blunter face and you've pretty much got the picture. The tools, however, were made by an as-yet-unidentified species of human, likely similar to the people who inhabited Georgia around the same time. No bones of either were found in the same level with the elephant, but the turds and tools brought ancient humans and hyenas into contact once more. Signs of their coexistence have been found from the Iberian Peninsula to Indonesia, but, as M. Patrocinio Espigares and coauthors write in a new paper, this is the first tentative sign of interaction between the two scavenging species.

Exactly what transpired at Fuenta Nueva-3 way back in the Pleistocene is obscured by the nature of the evidence. The surface of the fossil mammoth bones had weathered prior to exposure, possibly obscuring any expected bite marks or tool scrapes. That is if any were left on the bones at all. Mammoth bones had a thick periosteum - a membrane that surrounds bones - which would have made them resistant to recording tool marks. Not to mention that the arrangement of the skeleton in fine sand indicates relatively rapid postmortem burial, so this pachyderm may have still had a great deal of flesh on it when blanketed by sediment.

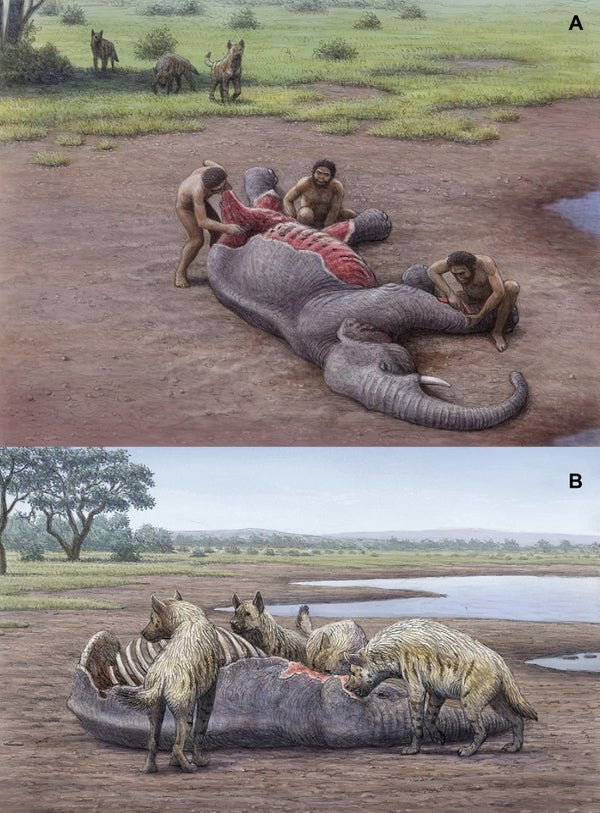

Humans and giant hyenas take their turns at a mammoth carcass. Credit: M. Antón, Espiagres et al. 2016

While remaining tentative about the scenario, Espiagres and colleagues propose a sequence of events that goes something like this. Humans arrived first, cutting off the limbs and possibly the skull of the mammoth, transporting them elsewhere to feast at their leisure. The hyenas hung back - perhaps driven off by the band of humans - but when the coast was clear they moved in to eviscerate the carcass and sup on the innards until the body was covered up.

This isn't the only way the possible conflict could have played out. Modern hyenas, for example, are capable of removing limbs or other parts of a carcass and toting them off. They could have arrived first and wrenched off those muscular elephant limbs. The only piece of evidence that favors an early arrival for the humans is that there are hyena feces around the mammoth skeleton where the limbs would normally be, perhaps indicating that the legs were gone by the time they arrived. Still, there's no fossil time clock to tell us who was munching on the carcass when.

How humans and hyenas broke down the mammoth carcass found at Fuenta Nueva-3 is clouded. The fossil record can only take us so far. But the stone flakes and carnivoran droppings bring the human and bestial scavengers down into a narrow window of time, perhaps only a matter of days. Imagine hacking away at an elephant thigh, looking over your shoulder to check for round-eared bone crushers behind you. Or, from the hyena's point of view, driving your muzzle into a mammoth's stomach, trying to grab a chunk of viscera before some annoying biped chucks a rock at you. It's a rough cut, undeniably, but it's still a tense slice of our world's Ice Age story.

Reference:

Espigares, M., Martínez-Navarro, B., Palmqvist, P., Ros-Montoya, S., Toro, I., Agustí, J., Sala, R. 2016. Homo vs Pachycrocuta: Earliest evidence of competition for an elephant carcass between scavengers at Fuente Nueva-3 (Orce, Spain). Quaternary International. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2012.09.032