This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

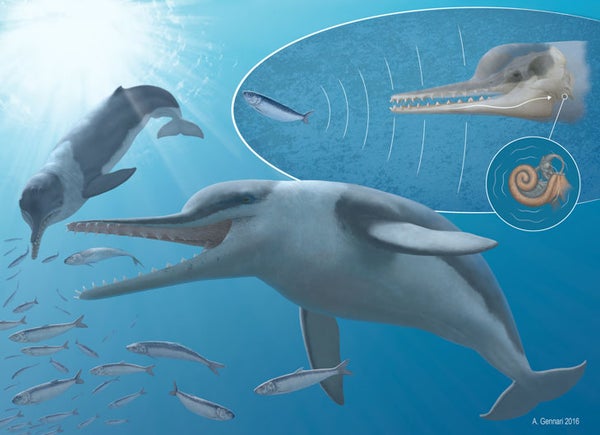

Toothed whales experience the world in a way we'll never fully appreciate. That's not only because they spend their lives at and beneath the surface of the waves, but because they can see with sound. Echolocation is their secret, allowing them to do everything from navigate turbid waters to locate squishy squid hiding in the deep dark, and in recent years paleontologists have been bringing the origin of this amazing ability into greater and greater focus. The latest cetacean to contribute its skull to science, Echovenator sandersi, even suggests that the beginnings of ultrasonic hearing started far earlier than experts previously supposed.

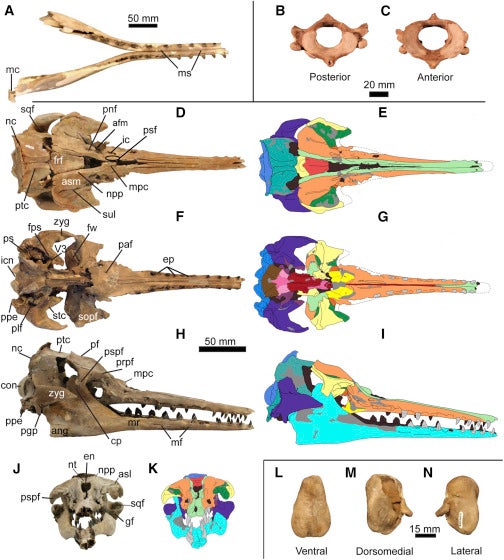

Described by paleontologist Morgan Churchill and colleagues, the 27-24 million year old whale is represented by a nearly complete skull and a neck vertebra. It's a lovely fossil with a sharp grin, but the most important details of Echovenator are much more subtle. The inner ear of this ancient whale, Churchill and coauthors write, show specializations seen in whales capable of making and hearing high-frequency sounds. Given that Echovenator is an archaic form of toothed whale - technically known as an odontocete - this suggests that ultrasonic hearing evolved early in the group's history.

But it's not just Echovenator alone that's worth buzzing about. Previously some experts had suggested that echolocation-ready toothed whales had evolved from ancestors that could only hear low frequency sounds. But when Churchill and colleagues examined the hearing abilities of two hippos and 24 whales, both living and fossil, they found that whales started becoming sensitive to high frequency sounds early in their history. In fact, whales may have tuned in to higher frequencies before the two major groups alive today - the toothed whales and the baleen whales - split from each other. The ability to echolocate didn't immediately come with this sensitivity, but an inner ear capable of picking up higher frequencies opened the possibility for the ancestors of the whales who enjoy the ability today.

The bones of Echovenator. Credit: Churchill et al. 2016

Fossil Facts

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Name: Echovenator sandersi

Meaning: Echovenator means "echo hunter", while sandersi honors fossil whale expert Albert Sanders.

Age: Oligocene, between 27 and 24 million years old.

Where in the world?: Berkeley County, South Carolina.

What sort of critter?: A toothed whale belonging to an extinct group called xenorophids.

Size: Unknown.

How much of the creature’s body is known?: A nearly complete skull and a neck vertebra.

Reference:

Churchill, M., Martinez-Caceres, M., de Muizon, C., Mnieckowski, J., Geisler, J. 2016. The origin of high-frequency hearing in whales. Current Biology. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.06.004

Previous Paleo Profiles:

The Light-Footed Lizard The Maoming Cat Knight’s Egyptian Bat The La Luna Snake The Rio do Rasto Tooth Bob Weir's Otter Egypt's Canine Beast The Vastan Mine Tapir Pangu's Wing The Dawn Megamouth The Genga Lizard The Micro Lion The Mystery Titanosaur