This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Jurassic World wasn’t exactly a paragon of scientific accuracy. The movie, as its own characters acknowledge, went in for full-on monsters instead of prehistoric saurians as paleontologists understand them now. There’s no better example of the movie’s monsterism than the pterosaurs. At least the frog-dinosaur hybrids looked more or less like what experts expected of dinosaurs circa 1993. The pterosaurs, by comparison, were gibbering hellbeasts that didn’t look or act like the animals they were supposed to be. And that’s a real shame. In straying so far from the science, the movie missed an opportunity to do something truly scary.

The pterosaurs of Jurassic World – ostensibly Pteranodon and Dimorphodon – definitely watched a lot of 70s b-movies. That’s the only reason I can think of that would explain why they were obsessed with trying to pick people up and stab them with their jagged beaks. But imagine a towering, thick-necked pterosaur tottering around the park, plucking up hapless tourists and swallowing them whole. Even though it sounds more outlandish than anything seen in the film, there’s a scientific case that some pterosaurs were terrifying terrestrial stalkers of just this sort.

Paleontologists Darren Naish and Mark Witton have championed the terrestrial stalker hypothesis for some pterosaurs through a series of papers, and their latest argument in the case focuses on a little-known pterosaur from Transylvania called Hatzegopteryx. Relatively few bones of this pterosaur have been found so far, but enough has turned up to indicate that this was a huge animal related to the more famous Quetzalcoatlus from North America, belonging to a pterosaur subgroup called azhdarchids. Despite having a long and relatively slender neck expected for these pterosaurs, though, Naish and Witton suggest that Hatzegopteryx had a shorter, stockier neck that would have made this animal a terror for little morsels skittering over the landscape.

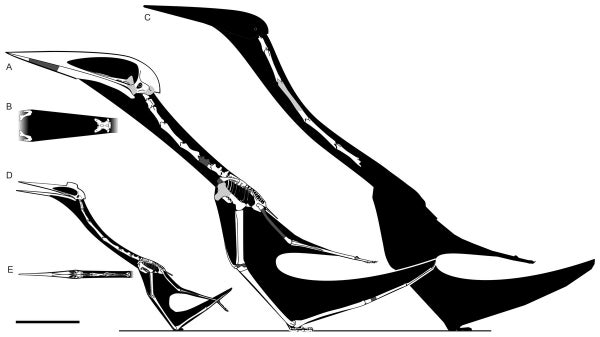

A reconstruction of Hatzegopteryx (A) compared with the noodle-necked Arambourgiania (C) and Quetzalcoatlus. Credit: Naish and Witton 2017

The key piece of evidence is a single neck vertebrae, which Naish and Witton propose was the seventh in the series. It’s a boxy bone, about nine and a half inches long and nearly as wide. This isn’t like the “elongate, often tubular neck vertebrae” expected for these pterosaurs, and seems to fit previous work by Mátyás Vremir, these authors, and others that the big pterosaurs of Hațeg were “robust-necked” forms starkly different from their close cousins.

Exactly what Hatzegopteryx looked like awaits the discovery of more complete remains, but, working with the unusual vertebra and what’s known of related animals, Naish and Witton propose this pterosaur indeed had a neck that was proportionally about half the length of what is expected for azhdarchids, not to mention more muscular. These pterosaurs were not just different heads of more or less the same chassis. Azhdarchids varied more widely than expected.

But this isn’t just about size. Naish and Witton also calculated how the Hatzegopteryx bone would handle certain stresses and strains compared to other pterosaurs of its ilk. The neck of Hatzegopteryx appears to have been stronger than that of its more noodle-necked relatives. The question is why.

Known Hatzegopteryx skull bones hint that this pterosaur had a wide, large, and heavy skull, Naish and Witton write. A stout, strong neck would be better adapted to holding up a heftier head. Taken together, though, these traits might be a hint that Hatzegopteryx and similarly-proportioned azhdarchids were almost like marabou storks, shuffling around and plucking up smaller dinosaurs and other prey, including meals too large to eat all in one go. In fact, Naish and Witton point out, a lack of large predators on Cretaceous Hațeg may have provided an opening for pterosaurs like Hatzegopteryx to step into the role. “[I]ts size, robust anatomy, and the deficit of other large carnivores in well-sampled European deposits implies that [Hatzegopteryx] may have been an arch predator in its community,” Naish and Witton write.

Now take this back to the movies. Imagine if the misguided genetic engineers of Jurassic World had created something like Hatzegopteryx – a pterosaur standing nearly as tall as a giraffe, immense wings folded as it shuffled forward. An annoying kid – never in short supply in any Jurassic Park film – might be tempted to laugh, only to find themselves plucked up and sliding down the throat of the toothless giant. Truth isn’t just stranger than fiction. It’s scarier, too.

[Full disclosure: I was the science adviser for the Jurassic Worldwebsite in 2015.]

Reference:

Naish, D., Witton, M. 2017. Neck biomechanics indicate that giant Transylvanian azhdarchid pterosaurs were short-necked arch predators. PeerJ. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2908