This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Mammals in the Age of Dinosaurs were supposed to be meek and mild. They lived in the shadows of the great reptiles, the story goes, squeaking out a timid existence for fear of being gobbled up. Think of a shrew and you get the picture. But that classic image is woefully out of date.

Just as dinosaurs have undergone a renaissance since the 1970s, so have the mammals that lived alongside them. There were twitchy little insectivores, yes, but a flow of new discoveries and analyses have shown that mammals and their relatives evolved into an impressive variety of forms. There were Mesozoic equivalents of flying squirrels, aardvarks, raccoons, beavers, and more. Now a new study of a classic Cretaceous mammal adds a little more resolution to the emerging image. One of North America's Mesozoic marsupials had a hell of a bite.

Didelphodon vorax has been known to paleontologists for well over a century. The famously fractious naturalist O.C. Marsh named the 68-million-year-old marsupial back in 1889. Until now, though, the published skeletal material has primarily consisted of teeth, jaws, and a few postcranial parts. Paleontologist Gregory Wilson and colleagues amend that with a new report on a lovely Didelphodon skull and other pieces recovered from the badlands of Montana and North Dakota.

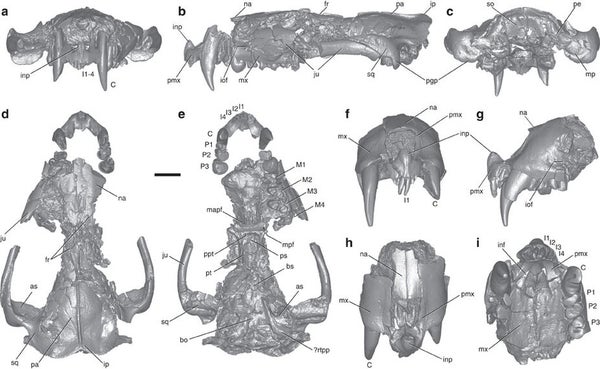

The skull of Didelphodon. Credit: Wilson et al. 2016

The skull of Didelphodon is wide and low. It has something of a compressed badger look about it, cheeks flaring wide to make space for powerful jaw muscles. And the beast's teeth only underscore that Didelphodon had a fearsome bite. Behind the mammal's canines are dome-shaped premolars and cheek teeth capable of a shearing through plant or flesh alike. Didelphodon had a varied toolkit for piercing, crushing, and cutting.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Bringing CT scans and other resources to bear, Wilson and colleagues put together a clearer view of what Didelphodon was capable of. From bite force and tooth bending stress estimates, the researchers found that Didelphodon had a stronger canine bite than almost any other mammal its size, just below the abilities of today's North American river otter and European badger. And when the paleontologists adjusted the bite force for body size, they found Didelphodon had the strongest relative bite force of any known mammal, surpassing even spotted hyenas.

Exactly what Didelphodon ate is unclear. Paleontologists are always hopeful for more gut contents and coprolites. But from the microscopic damage to the fossil mammal's teeth, Wilson and colleagues propose that Didelphodon was a varied feeder that could have nabbed small vertebrates, crushed snail shells, broken open bones, and supplemented all that protein with some Mesozoic salad. When you've got an incredible bite, the world is your oyster.

Reference:

Wilson, G., Ekdale, E., Hoganson, J., Calede, J., Vander Linden, A. 2016. A large carnivorous mammal from the Late Cretaceous and the North American origin of marsupials. Nature Communications. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13734