This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

It’s easy to treat dinosaurs as a monolith. We often talk about them as if they are, as if a sparrow were no different than a heavily-armored Ankylosaurus. But the truth is that "dinosaur" is just about as informative as "mammal" when it comes to capturing the essence of a group of animals. It’s a broad label that, by itself, doesn’t do very much at all to convey the diversity and disparity of the species contained within it.

If we begin at the other end of the spectrum – starting at species – the differences pop out at us, each and every entity representing a twig that joins others in a broad evolutionary tangle. And navigating that taxonomic nest is no simple task. The more we learn, the more divisions seem to go from stark to blurry. Or traits that once cleanly applied to just one group turn out to need a suitcase full of caveats, if they don’t crumble away entirely. Consider the ceratopsids.

Ceratopsids are the great horned dinosaurs. They’re the large, spiky, quadrupedal herbivores that emerged late in the Cretaceous and proliferated throughout North America and – as we’ve recently learned – Asia. And if you’re more than a casual dinosaur fan, you don’t need me to tell you that there were at least two flavors of ceratopsids running around – the centrosaurines and chasmosaurines.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

When I was a kid, these two horned dinosaur lineages seemed readily distinguishable from each other by the way they wore their ornaments. The chasmosaurines – represented by the likes of Triceratops and Chasmosaurus itself – had relatively subdued ornamentation on long frills, prominent brow horns, and relatively small nasal horns. On the other claw, the centrosaurines – represented by Centrosaurus, Styracosaurus, and their kin – are immediately recognizable from short frills that bristled with elaborate ornaments, and while they had short brow horns their nasal horns were much more impressive points.

That equation was simple enough to follow. If you’re looking at a dinosaur with an expanded frill and prominent brow horns, you’ve got a chasmosaurine. But if that frill has extended ornaments and the dinosaur has a long nasal horn, you’ve got a centrosaurine. It was handy and tidy, at least until a wealth of horned dinosaur discoveries in the last decade have rewritten what we thought we know about these dinosaurs.

The anatomical split between these two lines of horned dinosaurs was based on fossils that were about 75 million years old and younger. And for that range of about 9 million years, it works. But as paleontologists have dug into older rocks to trace the earlier days of the ceratopsids, the old dichotomy has broken down. A new study by paleontologist Caleb Brown helps highlight the more complicated picture.

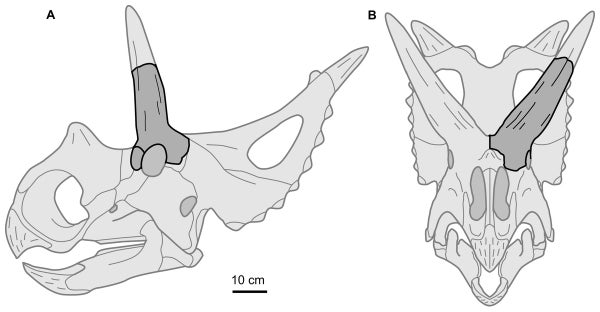

Brown focuses on two isolated horncores found in the 78.5 million-year-old strata of Alberta’s Foremost Formation. That might not sound like much, but they’re from a little-known time in horned dinosaur evolution – when the chasmosaurines and centrosaurines were undergoing an evolutionary radiation that would result in a dazzling array of decorated species up and down western North America.

Following the old rules, an expert would likely categorize the postorbital horn cores as those of a chasmosaurine. They are heftier and represent a longer ornament than what’s seen in dinosaurs like Centrosaurus. But when you get down to the details, Brown writes, these are the brow horns of centrosaurines – and possibly the horncores of the recently-named Xenoceratops from about the same time.

The identification of these long horn cores as centrosaurine bones isn’t a huge shock. Other centrosaurine dinosaurs – such as Nasutoceratops from the roughly 75 million-year-old rock of Utah – have been found with long brow horns and stubby nasal ornamentation. But the find underscores that centrosaurines didn’t always have the same look. There was a time when they had more subdued displays on their frills, longer brow horns, and shorter nasal horns. The old dichotomy doesn’t really work, and may actually confuse the identity of little-known dinosaurs. As I wrote earlier this month, Medusaceratops was thought to be a strange chasmosaurine until additional bones showed it to be a cousin of Centrosaurus.

“The two postorbitals described here represent some of the earliest ceratopsid remains,” Brown writes, “and indicate a form with clearly massive, dorsolaterally projecting, straight postorbital horncores.” And if they are indeed centrosaurine bones, the original centrosaurine look involved long brow horns and only later switched to short brow horns and crazy frill ornamentation. As ever, the question is why. If these horns were social signals more than weapons, then perhaps chasmosaurine dinosaurs essentially stole the look of their cousins. That is, maybe the proliferation of co-occurring horned dinosaurs among two different lineages urged on the evolution of two different sorts of looks by about 75 million years ago, making it easier for species to identify their own kind at a distance. Or perhaps there’s something else about the behavior or ecology of the animals that the depth of time has blinded us to. Either way, dinosaurs continue to defy our expectations.

For more – including glorious illustrations – see the Royal Tyrrell’s official blog post about Brown’s new paper.