This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

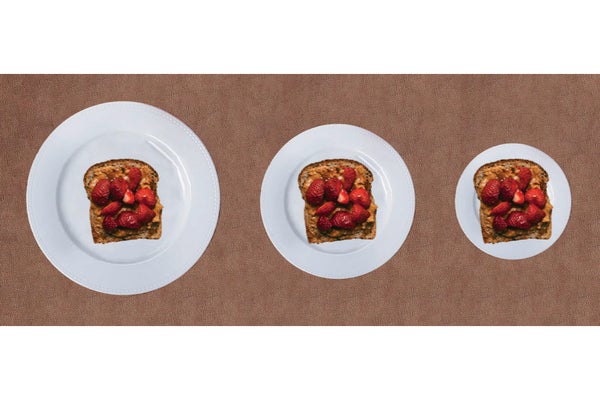

It’s one of the usual dieting ‘hacks’ from lifestyle websites and magazines: if you use small plates for your meals, your food portions will look considerably larger—and presumably feel more filling—than if you use bigger plates with lots of empty space surrounding your chow.

The deception has its origin in the Delboeuf illusion, named after the Belgian psychologist who discovered it in 1865. In its classical depiction, two black circles of the exact same size are surrounded by respectively large or small white circles. The arrangement makes the black circle inside the small white circle look significantly bigger than its doppelganger inside the large white circle. Replace black circle with strawberry cheesecake, and white circle with plate, and you have the means to make your dessert seem bigger or smaller just by changing your dinnerware.

According to previous research, the trick should work: in a 2012 study, scientists asked participants to serve themselves soup into bowls of different sizes. People using larger bowls poured more soup than those with smaller bowls, a difference that the researchers attributed to the Delboeuf effect. The results from this experiment and similar others have started to have everyday repercussions: in the last few years, restaurants have begun to serve meals on smaller tableware, aiming to take advantage of this illusion.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Now, a new paper by psychologists Noa Zitron-Emanuel and Tzvi Ganel, of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel, indicates that there may be more—or maybe less—than meets the eye in the Delboeuf illusion… when food is concerned.

The researchers set out to determine whether appetite might affect people’s susceptibility to food-size illusions. Prior work had suggested that this should be the case, given the known effects of other motivational factors on perception (for instance, poor children see coins as larger in size than wealthy children do).

Zitron-Emanuel and Ganel presented examples of the Delboeuf illusion to two groups of experimental participants. One group was mildly food-deprived, after abstaining from eating for 3 hours prior to the experiment. The other group was asked to eat during the hour before the experiment, and was therefore not deprived. The Delboeuf illusion images included food items (pizzas on trays) and non-food items (black circles inside white circles, and hubcaps within tires).

The results showed that the two groups were equally susceptible to the Delboeuf effect as related to non-food items. However, when participants were asked to compare the sizes of pizzas on serving trays, the food-deprived group experienced a significantly smaller illusion than the non-deprived group. In other words, whereas both subject groups were similarly inaccurate when judging the sizes of circles and hubcaps, hungry participants estimated pizza sizesmore accurately than satiated participants did.

These findings confirm the prediction that motivational factors affect how we perceive food, and are moreover in line with the results of a study published last year, which showed that the food-size illusion is smaller in overweight individuals than in normal-weight people.

In practical terms, Zitron-Emanuel and Ganel’s data indicate that our attempts to ‘trick’ ourselves into eating smaller portions by using the Delboeuf illusion are regrettably doomed to failure in situations when we feel hungry—as we’re prone to do while trying to stick to a diet.