This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

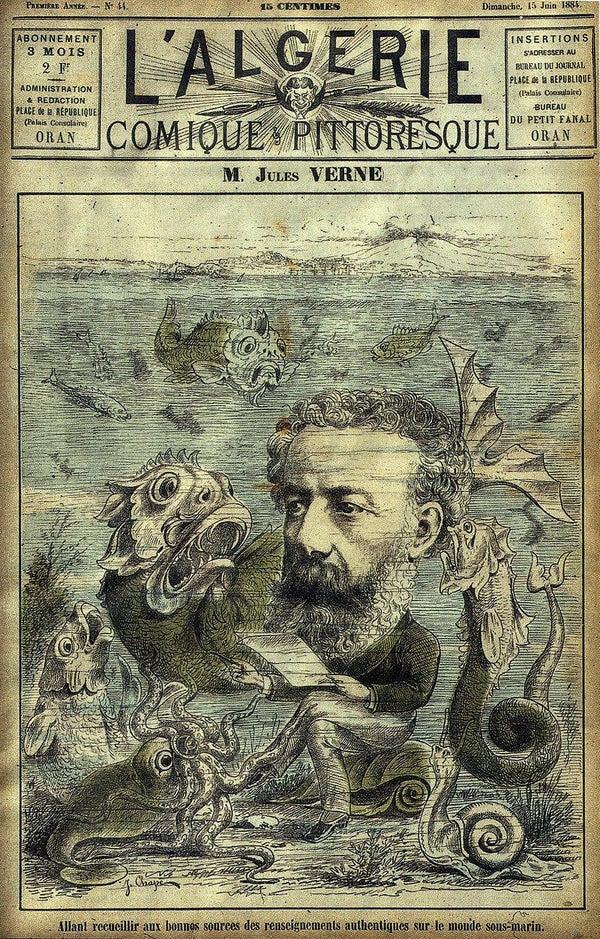

This month marks the 190th anniversary of Jules Verne’s birth, on February 8, 1828. Known as the Father of Science Fiction, Verne not only authored classic adventure novels such as From the Earth to the Moon and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, but he also influenced the Surrealist movement and the Steampunk aesthetic, and inspired figures such as the cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, the oceanographer Jacques-Yves Cousteau, and the Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton.

One reason for Verne’s enduring and widespread cultural legacy is that he took great pains to inform himself about the technological frontiers of his time, grounding his fiction in contemporary science research. Indeed, Verne’s scientific examinations were not constrained to ballistics, aerodynamics or marine biology (the subject matters that he is most famously associated with), but they extended to the domains of optics, perception and illusion. In fact, Verne was intrigued enough by visual tricks to place them at the crux of several of his stories. At least three of his works forestall neuroscience fiction at its best: The Green Ray, The Kip Brothers and The Carpathian Castle.

We previously wrote about the perceptual and optical bases for ‘green rays’ such as that in Verne’s eponymous novel.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Here we discuss the facts and fiction of the optical illusions showcased in Verne’s The Kip Brothers and The Carpathian Castle.

The Kip Brothers

At the climax of The Kip Brothers, published in 1902, the protagonists find themselves unjustly accused of murder. Technology comes to the rescue in the form of optography, a process consisting on retrieving an image, or optogram, from a corpse’s retina. Verne’s contemporaries believed that the last image that a person saw before dying would engrave itself on his or her retinas, and might be later retrieved to illuminate forensic matters. The idea is not as preposterous as it sounds. In 1876, the physiologist Franz Christian Boll discovered rhodopsin, a retinal pigment that bleaches in the light and recovers in the dark. Shortly afterwards, Wilhelm Kühne, a German physiologist, developed a method to fix the bleached rhodopsin and subsequently extract an image from the eye. Kühne would keep rabbits—his experimental subjects—in the dark for a number of minutes, to let rhodopsin accumulate in their retinas, and then expose the animals to brightly lit windows. The rabbits were then quickly sacrificed, and their eyeballs removed for processing. Kühne’s most successful experiments show clear images of the barred windows seen by the rabbits right before their deaths, imprinted on the animals’ retinas. Alas, later research showed optometry to be quite limited. The method was unable to produce optogram of any images other than simple, high-contrast patterns—such as barred windows. The execution of a convicted murderer, Erhard Gustav Reif, in 1880, provided the means to achieve the first human optogram, but the results were ambiguous. The optogram, which has not survived, is reported to have resembled the blade of the guillotine that ended Reif’s life, but the problem with that interpretation is that Reif was blindfolded right before the blade fell. Some believe that the optogram, instead, depicted the steps that Reif climbed to get to the guillotine. Forensic optography enjoyed some popularity into the 20th century, but eventually fell out of favor. Unlike fictional scenarios such as The Kip Brothers, in which optography revealed the true culprits, the technique has failed to produce conclusive and reliable evidence in real life.

Kühne’s rabbit optograms. Left: A rabbit retina without an optogram. Middle: Optogram of a seven-paned window. Right: Optogram of three side-by-side windows. Credit: Kühne 1877

Credit: Patrick Brinksma Unsplash

The Ghost in the Carpathian Castle

The Carpathian Castle, published in 1892, is a gothic tale set in Transylvania. The story may have inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula (published in 1897), but Verne and Stoker resolved the supernatural happenings in their respective novels in diametrically opposed ways. Whereas Stoker’s bloodthirsty ghouls existed outside the realm of science, Verne’s otherworldly apparitions ended up being fully explained by technology.

In Verne’s tale, inexplicable happenings in the Carpathian castle have convinced the neighboring villagers that the devil occupies it. The hero sets out to investigate and ultimately finds out (Spoiler Alert!), Scooby-Doo style, that the creepy ghost haunting the castle has been manufactured by an optical apparatus deployed by the castle’s owner.

“It was a simple optical illusion (…). By means of glasses inclined at a certain angle calculated by Orfanik, when a light was thrown on the portrait placed in front of a glass, La Stilla appeared by reflection as real as if she were alive, and in all the splendor of her beauty.”

The ghost-producing device described in The Carpathian Castle first amazed audiences at a theatrical premier of a Dickens novella, on December 24, 1862: The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain.

Conceived as a stage illusion, the spectral manifestation summoned by the joint efforts of Henry Dircks, a civil engineer, and John Henry Pepper, a chemist and science popularizer, came to be known as “Pepper’s Ghost.” It required hiding an actor below the stage, and using an inclined glass—placed in front of the stage, and invisible to the audience—to project the actor’s reflected image behind the glass, so it appeared to interact with onstage performers.

Pepper’s ghost was a huge success with nineteenth-century audiences, and it remains in use today, for instance at Disneyland’s “Haunted Mansion.” Verne may have attended theatrical productions featuring Pepper’s Ghost, or at least known about the technology behind its creation, before writing The Carpathian Castle.

Verne’s imagination allowed him to predict many technical feats and inventions well ahead of his time. Examples include newscasts, the Moon landing, and skywriting. But other times he relied on existing scientific knowledge. Whereas Verne has been credited for foreseeing holography and television, the mysterious presence in The Carpathian Castle was the product of well-established nineteenth-century technology.