This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The following text is partially reprinted from the 2016 Scientific American Mind’s special issue on illusions.

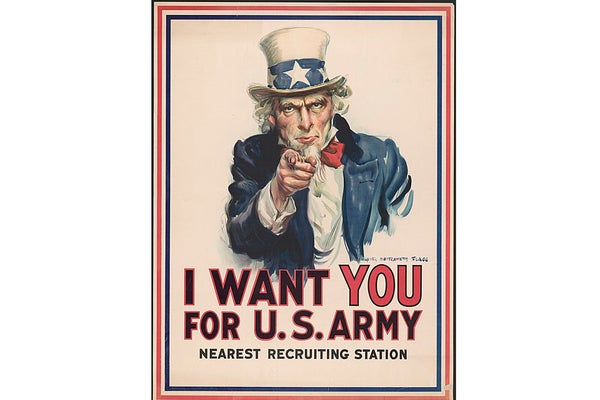

On Uncle Sam’s 242nd birthday, here’s an oldie but goodie, which we have featured in our previous writings about face illusions.

In this image, painted by the artist and illustrator James Montgomery Flagg and depicted in World War I recruiting posters, Uncle Sam’s eyes and finger seem to be pointed directly at you, no matter your viewing angle. You can experience the same kind of illusion when you look at portraits in an art museum, and their painted eyes appear to follow you as you walk.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A 2004 study by vision scientists Jan Koenderink, Andrea van Doorn and Astrid Kappers, then at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, and James Todd of Ohio State University, concluded that, contrary to popular belief, this captivating illusion does not require special artistic talent from the painter. Instead, all that is required is that the subject of the portrait looks straight ahead, and the observer’s visual system takes care of the rest. The deceptively simple explanation is that when we look at a real human face (or any other object) in our three-dimensional physical world, the visual information that specifies near and far points changes with our viewing angle. But when we observe a two-dimensional painting or photograph hanging on the wall or a poster such as Uncle Sam’s depiction here, the visual information that defines near and far points remains unaltered by our viewing angle. The brain interprets this information as if it pertained to a 3-D object, however. That interpretation is what creates the eerie sensation that a portrait’s eyes are following you.

Here is another couple of illusions to celebrate the holiday. Enjoy the fireworks!