This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

It’s good to learn something new every day. The Internet makes that easy, placing knowledge at our fingertips. Learning doesn’t require consulting experts. We can enlighten each other. Wikipedia crowdsources knowledge by asking everyone, as Michael Feldman does on the radio, “Whad’Ya Know?” I learn something from you; you learn something from me.

With a slight tweak, this type of crowdsourcing can also be used to learn something that not a single one of us yet knows. Crowdsourcing for scientific discovery, known as “citizen science,” involves asking everyone, “Whad’Ya observe, experience, find or ponder?” Assemble contributions together in the appropriate way and voila! New knowledge.

With a “more heads are better than one” approach, citizen science leads to discoveries that would not be possible with scientists working alone.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

To bring heads together, over 40 U.S. federal agencies have joined the Federal Community of Practice on Citizen Science and Crowdsourcing. Some already make elaborate use of citizen science, like the U.S. Geological Survey relying on people who watch birds (Breeding Bird Survey), notice when flowers bloom (Nature’s Notebook) and experience earthquakes (Did You Feel It?), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration relying on weather updates from Severe Weather Spotters, Daily Weather Observers and through the recent mPING app. Other agencies are getting their feet wet, like the NASA (S’COOL Roving Cloud Observers), the Federal Communications Commission (Measuring Broadband America), and the National Archives (Citizen Archivist Dashboard). Today, if you follow former President Kennedy’s iconic advice and ask what you can do for your country, the resounding answer is: citizen science.

It makes sense to draw on We the People. According to government statistics on occupations, there are about 6 million scientists in the U.S. Yet our human capital includes over 300 million potential citizen scientists (plus, one does

USA-National Phenology Network citizen-scientist Lucille Tower records the one millionth observation on maple vine in the large nature database as part of USGS's Nature's Notebook project. (Source: USGS)

not need to be an American citizen to be a citizen scientist in the U.S.). There is no need to limit our national energies for innovation and scientific revolutions to the small percentage of professionals when We the People can do citizen science.

The federal agencies have learned that coordinating citizen science is itself a science. The challenges traditional scientists deal with, such as data management, quality and potential sources of bias, have to be addressed in citizen science too. Plus, the challenges are often amplified by the scale of citizen science projects, which can involve tens of thousands of people contributing observations or micro-tasks towards a single research pursuit. Specialists in education, communication, information sciences, data visualization, human-computer interactions, and more are coming together to ensure rigorous citizen science. There are international membership organizations, such as the Citizen Science Association with a scholarly journal and conferences, to help foster science by the people.

The complexity of implementing citizen science drove the Federal Community of Practice on Citizen Science and Crowdsourcing to create a tool kit, which is being released tomorrow, to guide Federal agencies (and others) to harness the powers of curious people throughout the nation.

To celebrate the release and spur use of the tool kit, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and the Domestic Policy Council is hosting a citizen science forum from 8:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. on September 30 called “Open Science and Innovation: Of the People, For the People, By the People.” Citizen science projects are providing ways to overcome national challenges such as conserving pollinators, monitoring droughts, recovering from coastal flooding and improving health with low-cost sensors.

The White House event will be live webcast here, with live tweeting (#WHCitSci and follow @WhiteHouseOSTP and me @CoopSciScoop):

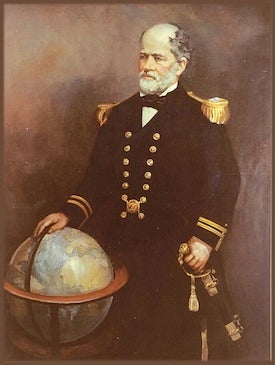

Although the federal took kit is a new development, federal agencies have long recognized the intellectual capital of We the People. For example, in the mid-1800s, U.S. Naval officer Matthew Maury wanted to chart the distribution and seasonal migrations of whales. He created his chart by asking sailors for their sightings. (Maury is a real character footnoted in the fictional story, Moby Dick).

Maury became the father of oceanography by charting the ocean currents and winds: a journey he completed without leaving his desk at the Depot of Charts and Instruments of the U.S. Navy. At the time, sailing the high seas was a risky undertaking. Not much had changed over the 25 centuries since Homer’s story of Odysseus, which is an epic navigational nightmare. Instead of multiple gods toying with sailors’ lives, mariners in the 1800s believed in false protections like not whistling on board for fear of challenging the winds. When sailors saw a shark, it was a bad omen; a cat on board was good luck. At the mercy of forces that appeared like whims, the voids in our understanding were filled with superstitious explanations.

Commander Matthew Fontain Maury, one of the pioneers of citizen science in 19th century, asked fellow sailors to report whale sightings in order to chart the marine mammals' distribution and seasonal migration. (1923 painting by Ella Sophonisba Hergesheimer/Wikimedia Commons)

To fill the void another way, Navy and merchant sailors dutifully began sending regularly recorded estimates of latitude and longitude, wind direction, wind speed and weather conditions to Maury. By aggregating observations from over 1,000 ships across the seven seas, Maury created wind and current charts that instantly made sailing safer and sped commerce. In this way, he used citizen science and crowdsourcing to identify the safest and most efficient ocean routes and earned the moniker “Pathfinder of the Seas.” Maury’s project continues to this day, administered by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, which is part of the Department of Defense, also a member of the Federal Community of Practice on Citizen Science and Crowdsourcing.

“Until I took up your work, I had been traversing the ocean blindfolded,” one mariner wrote to Maury. The tool kit created by the Federal Community of Practice on Citizen Science and Crowdsourcing is a how-to manual to guide federal agencies in removing more blindfolds.

We the People observe. We the People take note of the environment that surrounds us. We the People share our experiences. More is still unknown than known to us. We are navigating humanity’s future blindfolded. We the People can steer a better course with citizen science and learn something truly new every day.