This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Programming has changed. In first generation languages like FORTRAN and C, the burden was on programmers to translate high-level concepts into code. With modern programming languages—I’ll use Python as an example—we use functions, objects, modules, and libraries to extend the language, and that doesn’t just make programs better, it changes what programming is.

Programming used to be about translation: expressing ideas in natural language, working with them in math notation, then writing flowcharts and pseudocode, and finally writing a program. Translation was necessary because each language offers different capabilities. Natural language is expressive and readable, pseudocode is more precise, math notation is concise, and code is executable.

But the price of translation is that we are limited to the subset of ideas we can express effectively in each language. Some ideas that are easy to express computationally are awkward to write in math notation, and the symbolic manipulations we do in math are impossible in most programming languages.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The power of modern programming languages is that they are expressive, readable, concise, precise, and executable. That means we can eliminate middleman languages and use one language to explore, learn, teach, and think.

.jpg?w=600)

Figure 1

As an example, Figure 1 shows the breadth first search (BFS) algorithm expressed in the pseudocode used in a popular textbook. The authors designed this language to be more concise and readable than most programming languages at the time, which was 1989.

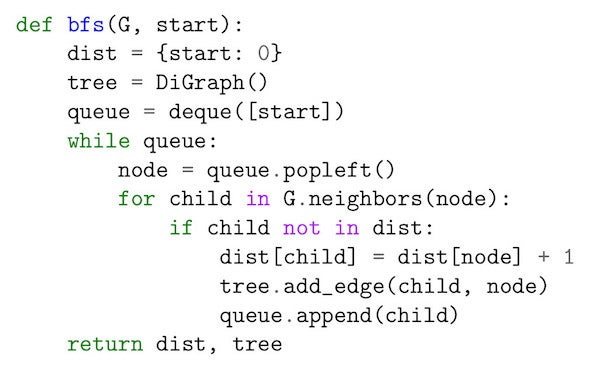

Figure 2 shows the same algorithm in Python. It is a few lines shorter than the pseudocode, and because it uses more words than symbols, I think it’s more readable. Also, unlike pseudocode, we can run it, display the results, and debug it.

Figure 2

Running programs is the whole point of programming, of course, but there is more to it. The ability to execute code makes programming a tool for thinking and exploring. When we express ideas as programs, we make them testable; when we debug programs, we are also debugging our brains.

Languages like Python are also ideal for learning and teaching. For example, I wrote a book recently about digital signal processing (DSP). I used Python to write a simple library and Jupyter (which is a software development environment) to compose online notebooks that combine text, code, and results, including images and sound clips.

As I developed the book, I wrote code to test my understanding and explain it to students at the same time. Students can run the code to develop a mental model, make changes to test their predictions, and extend my code for their projects.

Most textbooks and classes use math to teach signal processing, with students working primarily with paper and pencil. With this approach, the only option is to go “bottom up”, starting with the arithmetic of complex numbers, which is not the most exciting topic, and taking weeks and many pages to get to relevant applications.

With a computational approach, we can go “top down”, starting with libraries that implement the most important algorithms, like Fast Fourier Transform. Students can use the algorithms first and learn how they work later. They can see the most important ideas, like spectral decomposition, without being blinded by details. They can work on real applications, on the first day, that provide the motivation to go deeper. And they can have a lot more fun.To demonstrate, I wrote a Jupyter notebook called “Cacophony for the whole family.” If you click that link, you can see the code and listen to the examples. It uses the library I wrote to simulate the sound of a grade school band, with instruments out of tune and some children randomly playing the wrong note. It’s meant to be silly (and a little bit mean), but it also demonstrates aspects of how we perceive sound and interpret the pitch of a complex signal.

The languages I am calling modern are not particularly new; in fact, Python is more than 25 years old. But they are not yet widely taught in high schools and colleges. And even where they are adopted, they are often used in a style that does not take advantage of their power.

Modern programming languages are qualitatively different from their predecessors, but we are only beginning to realize the implications of that difference.

In a companion article, I present more ways to use Python to think, explore, learn, and teach.