This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Filmmakers are getting into the international conversation about climate and energy policy. Here are three important and beautiful films that caught our eye during the 2015-2016 international film festival circuit. One is the biography of a famous geologist who first studied ancient air trapped in sheets of ice, the second creates metaphorical melting worlds, and the third looks at what drives the fossil fuel industry.

The Ice and the Sky (Luc Jacquet, 2015)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

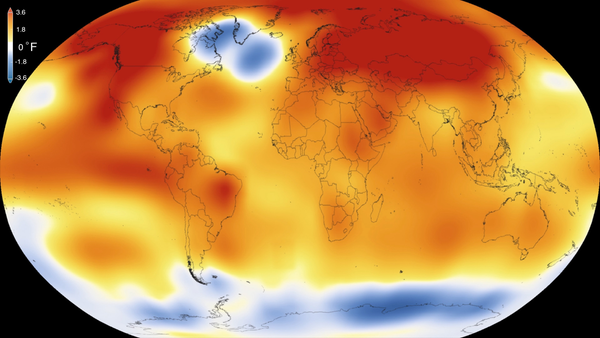

In 1956, glaciologist Claude Lorius left on his first trip to Antarctica, where he would spend the winter gathering previously undocumented meteorological and geophysical data. Three decades and 22 expeditions later, Lorius unveiled his groundbreaking findings: the irrefutable link between greenhouse gasses and climate, gleaned from glacial ice cores providing snapshots of the environment up to 800,000 years into the past. His key contribution? Realizing that air bubbles trapped in the cores could provide precise atmospheric snapshots of the past. Such a long view, extending over eight ice age cycles, allowed Lorius to look far beyond temporary or cyclic fluctuations, and the implications were clear: "Over the last 100 years, the CO2 produced by man is behind an unprecedented rise in temperatures on Earth."

That quote is drawn from The Ice and the Sky, a new feature documentary on Lorius' work which premiered on the closing night of Cannes last spring and is expected to be in U.S. theaters by late summer. The film was directed by Luc Jacquet, whose Academy Award-winning March of the Penguins proved he's no stranger to Antarctic himself. In fact, he first visited as an ecologist at the age of 23, the same age as Claude Lorius on his first expedition. Perhaps it is this familiarity with the material, both scientific and geographical, that makes The Ice and the Sky the uniquely dramatic experience it is, equal parts essential scientific procedural and gripping adventure story of survival at the ends of the earth. Following the record-shattering global temperatures of this winter, it couldn't be more relevant than now.

PLANET ∑ (Momoko Seto, 2014)

Experimental filmmaker Momoko Seto's works appear to show other worlds, but her techniques, and themes, are often distinctly terrestrial. Her ongoing "Planets" series turns deceptively ordinary natural phenomena, such as mineral growth or mold creeping over cauliflower, into unearthly postcards from deepest space, through a careful juxtaposition of macro photography, timelapse, and slow-motion. With an almost scientific methodology, Seto rigorously experiments with her subjects to ensure that several weeks of filming will yield that perfect ten-second shot. Or, like any laboratory work, adjust her protocols and reshoot when things turn out unexpectedly.

"I use images of natural disasters to build the script," Momoko described in an email. Her latest, PLANET ∑, which won the Audi Short Film Award at the 2015 Berlinale, was inspired by an article on the Snowball Earth Hypothesis. Following the displacement of atmospheric greenhouse gases by oxygen, the Earth was "completely frozen 2.2 billions years ago, like a snowball." Volcanic activity eventually released the needed CO2 to warm the planet again and allow life to explode, but in Seto's film the process doesn't reach equilibrium and warming continues dangerously, in an eerie premonition of current climate risks. The film also references the current decline of honey bee populations, but the results are anything but didactic or obvious. Instead, Seto rearranges her sources into ambiguous planetary cycles that turn a darkened mirror on our own.

Deep Time (Noah Hutton, 2015)

Deep Time from Couple 3 Films on Vimeo.

Of course, climate change is not a purely environmental issue, but an economic one. Noah Hutton's Deep Time studies our complicated ties to fossil fuels at their source, in the oil shale of North Dakota. The discovery of the Parshall Oil Field in 2006, along with the development of fracking and horizontal drilling extraction methods, have given North Dakota tens of thousands of new jobs and billions in revenues. Hutton's elegantly shot but unsettling film focuses on the human impact of the boom, juxtaposing these irresistible short-term economic benefits against new social tensions and longer-term impacts on community and landscape.

The locals of boom epicenter Stanley "were insistent that it wouldn't change their way of life," Hutton told us by email, describing how he was drawn to the subject back in 2008. "And more generally, it seemed like an important juncture in American history: do we start drilling our own oil here, or do we transition in a serious way to renewables? Well, we started drilling, and now eight years later I can say it did definitely change the way of life out there for many people." These subjects emerge from a vertical section of voices: local farmers leasing mineral rights, struggling residents of the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation, newly imported oil company workforce, and politicians backing increased domestic oil extraction. The darker side of the boom appears in the shadow of the bold economic figures: corners cut to increase profits, contaminated water, increasing heroin use and crime, and local government corruption.

Deep Time takes its title from 18th-century Scottish geologist James Hutton's concept of geologic time. And time itself is worked deeply into the film, with ancient fossil deposits in the Alaskan permafrost juxtaposed against the rapid changes taking place in North Dakota. It is over this much longer scale, the film subtly suggests, the greatest effects of the short term gains of so-called U.S. energy self-sufficiency may be felt. Now, a year after its debut at SXSW, the film will be available on iTunes starting May 1.