This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

On Yom Kippur in 1944, Mina Pächter lay dying of starvation in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. She gave her friend a package with one request--if he survived, he was to deliver it to her daughter living in Palestine. Its contents contained a collection of recipes, reflecting the tradition of mothers passing on books of handwritten cookbooks.

These recipes are published in In Memory’s Kitchen: A Legacy from the Women of Terezín edited by Cara De Silva. Michael Berenbaum, Director of the United States Holocaust Research Institute describes it as an unconventional cookbook. As he writes in its foreword, “It’s not to be savored for its culinary offerings but for the insight it gives us in understanding the extraordinary capacity of the human spirit to transcend its surroundings, to defy dehumanization, and to dream of the past and of the future.”

Mina Pächter was 70 when she was sent to Theresienstadt in 1942. Located in the garrison Czech town of Terezín, the Theresienstadt Ghetto was created in 1941 by the Nazis. It served many functions; in addition to being a transit camp, it was used as propaganda to project an image of Hitler’s benevolent treatment of Jews. Its main street included a foodless coffeehouse and a non-functioning bank. The camp consisted of prominent Jews--academics, musicians, artists, and intellectuals like Pächter, who was an art historian.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

An illustration of Theresienstadt's non-functioning coffeehouse from 1943. Credit: Bedřich Fritta Jewish Museum Berlin

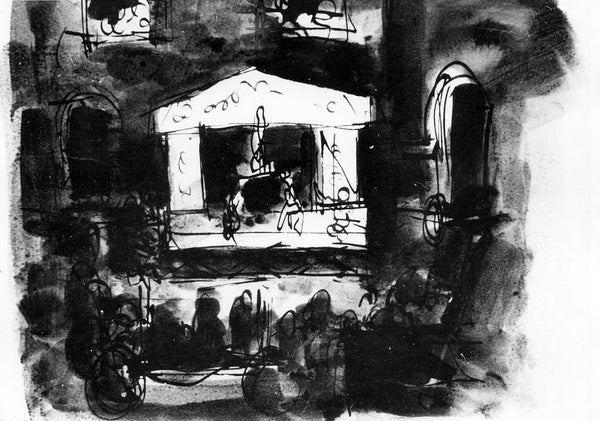

The intellectuals and artists imprisoned in Theresienstadt put on plays as a way to maintain their identity, creativity, and expression. Credit: Bedřich Fritta Ghetto Fighters House

Beneath its false veneer, Theresienstadt Ghetto was rife with disease, overcrowding, and malnutrition. Despite the hunger, conversations often centered around food with people recalling decadent dinners, debating culinary techniques, and hoping their recipes would one day be heirlooms passed onto children and grandchildren who could keep their culture alive through cooking.

As Holocaust survivor Jaroslav Budlovsky explains, these discussions functioned beyond preserving traditions. He writes, “The hunger was so enormous that one constantly ‘cooked’ something that was an unattainable ideal and maybe somehow it was a certain help to survive it all.” In an article for the New York Times, Lore Dickstein adds, “These recipes are an act of defiance and resistance, a means of identification in a dehumanized world. It was a life force in the face of death.”

It took decades to deliver the recipes recorded to Pächter’s daughter, Anny Stern. Stern had escaped the war by leaving for Palestine but by the time the manuscript was brought to Palestine, Stern and her husband had left for the United States to be with their son, a NASA scientist. Twenty five years after the initial promise, a stranger located Stern and gave her the collection of recipes.

Stern found she was unable to open the package for nearly a decade. When she finally felt she could look at its contents, Stern saw a photo as well as some letters but the majority of its contents was a hand-sewn book filled with nearly 80 recipes written on scraps of torn and weathered paper. The instructions for making classic dishes like strudel, dumplings, and kuchen are sometimes haphazard in style, often use imprecise measurements, and occasionally omit steps to follow. In other words, they are just what you'd expect in a recipe passed on from family.

In Pächter’s recipe for Gefüllte Eier (cold stuffed eggs), part of her instruction for garnishing the eggs is to “let fantasy run free.” That step was a vital part of life at Theresienstadt according to Bianca Steiner Brown, the translator of the recipes and former Theresienstadt inmate. She explains, “In order to survive, you had to have imagination. Fantasies about food were like a fantasy that you have about how the outside is if you are inside.”

______________________

Matzo Pudding

(from In Memory’s Kitchen: A Legacy from the Women of Terezín via the Los Angeles Times)

Make a batter from 8 egg yolks, 200 grams sugar, grated lemon peel and the egg whites, stiffly beaten (without flour). Grease a baking dish with goose fat, dampen thin matzos with wine or water. In a baking dish, make a layer of matzos, sprinkle them generously with hot goose fat, coarsely chopped almonds, cinnamon, pour some of the batter and continue making layers with matzos, almonds and cinnamon and always sprinkle with hot goose fat, until all the batter is used; there should be 8-9 layers. Bake in a hot oven.