This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Dogs look at us, alright. They look at us for food, attention, throw the ball already, you name it.

But there’s another type of looking that dogs do that offers a window into dogs' minds. Meet "looking time."

Looking time is exactly what it sounds like — the amount of time spent looking at something. Looking time is often measured to find out how something is perceived or interpreted by a subject, and numerous species — ourselves included — have participated in looking time studies.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In some experimental paradigms, a long look indicates expectancy violation, similar to the, "Wait what?" double-take we’re all familiar with. In 2009, University of Sussex researchers reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that when a horse saw a herd-mate disappear behind a barrier, the horse looked longer if they then heard the call of a different herd-mate coming from where the other horse had disappeared ("I just saw Joe walk over there, so how can Billy be making noise over there? I didn’t see Billy go by. Strange.”). But when a call from the horse who had just walked past was played, horses didn't look longer because hey, Joe just walked by, and there's Joe making some noise. Good ol' Joe.

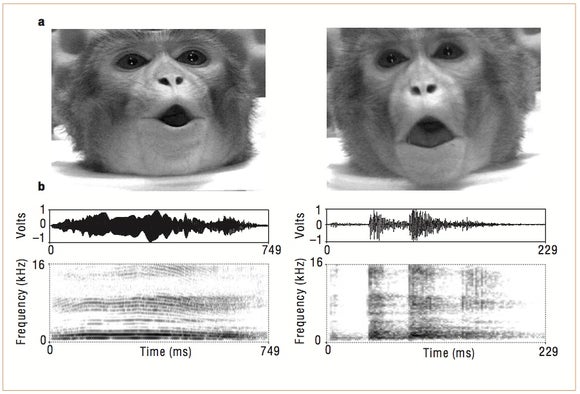

Tweak the paradigm slightly, and a long look suggests congruence or matching, the recognition that two things are similar. A 2003 Nature study presented rhesus monkeys with side-by-side video clips of a monkey displaying one of two very different visual displays; one was a 'coo' face (associated with an affiliative, friendly vocalization) and the other was a 'threat' face (associated with a threatening vocalization). When the video clips were paired with audio playback of either the coo or the threat call, monkeys looked longer at the face that matched the noise being played: play a coo vocalization and monkeys looked longer at the coo face, play a threat vocalization and monkeys look more toward the threat face. The researchers describe this multisensory integration as "the first demonstration of audio-visual integration in an animal vocal communication system.”

Figure 1 from Ghazanfar and Logothetis (2003). a, Video frames of facial gestures made during coo (left) and threat (right) calls. b, Oscillograms (top) and spectograms (bottom) of the coo and threat vocalizations: coo calls are long and tonal; threat calls are short, pulsatille and noisy

Now back to our good friend and professional starer the domestic dog. What does their long look tell us about what they know and understand?

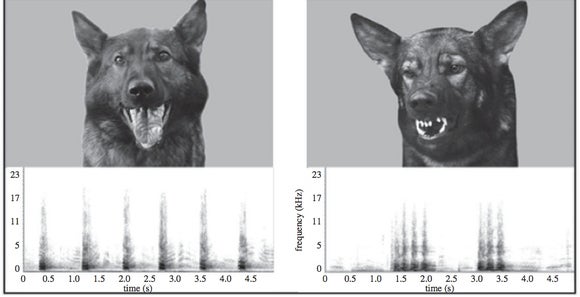

In a recent publication in Biology Letters, researchers from the University of Lincoln and the University of São Paulo used the cross-model preferential-looking test to see whether dogs can integrate visual and auditory cues that relate to emotions, namely positive (happy / playful) and negative (angry / aggressive). In this study, dogs saw two images presented at the same time — a happy dog face (loose, open mouth), and an aggressive dog face (mouth pushed forward in a c-curve, furrowed brow, and ears forward).* Similar to the rhesus monkey study, the visuals were paired with either a happy-dog vocalization or an aggressive vocalization to see where the dogs looked.

Figure 1 modified from Albuquerque et al (2016). Dog playful versus aggressive and correspondent vocalizations

Dogs performed like the rhesus monkeys! In 67% of the trials, dogs looked longer at the congruent face, the expression matching the vocalization. When it comes to happy and angry dog faces — and their corresponding sounds — dogs in this study integrated congruent signals.

Cross-modal integration makes sense when presented with an expressive dog, like the one above in the study, but what happens if a dog is paired with a potentially less-expressive member of Canis familiaris? Face off against Beast, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s Puli, and would it be more difficult for other dogs to integrate visual and auditory information (you know, after they sniff around to get past the dog-or-mop question)?

Or how about brachycephalic dogs like the Pug, Pekinese, or French bulldog? Unlike dolicocephalic or mesaticephalic dogs equipped with a long, pronounced muzzle, brachycephalic dogs are “characterized by an extremely broad skull base and short muzzle” (Case, 1999). Would it be as easy for dogs to identify emotional expression (and then integrate the corresponding vocalization) in dogs whose communicative signals might deviate from the classic displays of canid emotional expression?

*More on canine body language from the ASPCA here.

References

Albuquerque N, Guo K, Wilkinson A, Savalli C, Otta E, Mills D. 2016. Dogs recognize dog and human emotions. Biology Letters 12: 20150883.

Case L. 1999. The Dog Its Behavior, Nutrition, & Health. Wiley-Blackwell; 2 edition

Ghazanfar AA, Logothetic, NK. 2003. Neuroperception: Facial expressions linked to monkey calls. Brief communications Nature 423, 937—938.

Proops L, McComb K, Reby D. 2009. Cross-modal individual recognition in domestic horses (Equus caballus). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 947—951.