This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

In 1972 Thomas Kuhn hurled an ashtray at Errol Morris. Already renowned for The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, published a decade earlier, Kuhn was at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and Morris was his graduate student in history and philosophy of science.

During a meeting in Kuhn’s office, Morris questioned Kuhn’s views on paradigms, the webs of conscious and unconscious assumptions that underpin, say, Aristotle’s, Newton’s or Einstein’s physics. You cannot say one paradigm is truer than another, according to Kuhn, because there is no objective standard by which to judge them. Paradigms are incomparable, or “incommensurable.”

If that were true, Morris asked, wouldn’t history of science be impossible? Wouldn’t the past be inaccessible--except, Morris added, for “someone who imagines himself to be God?” Kuhn realized his student had just insulted him. He muttered, “He’s trying to kill me. He’s trying to kill me.” Then he threw the ashtray at Morris and threw him out of the program. According to Morris.*

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Morris went on to become an acclaimed maker of documentaries. He won an Academy Award for The Fog of War, his portrait of “war criminal”—Morris’s term—Robert McNamara. His documentary The Thin Blue Line helped overturn the conviction of a man on death row for murder.

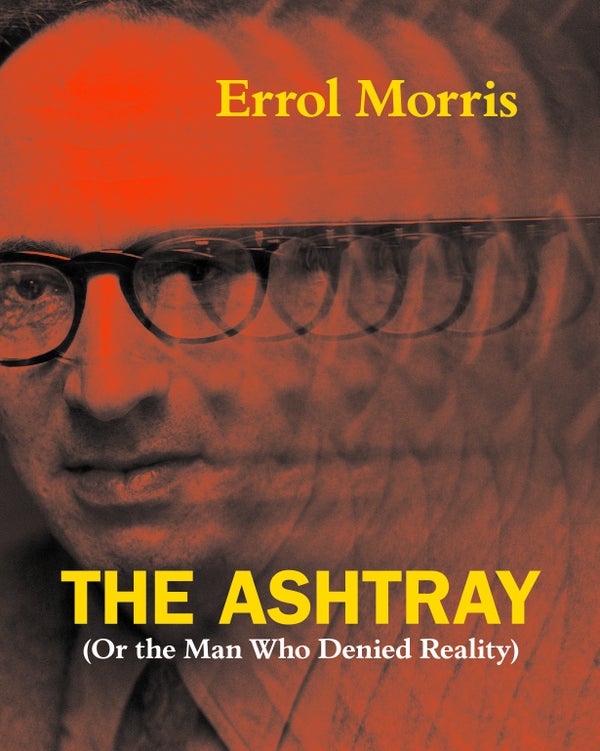

Morris never forgave Kuhn, who was, in Morris’s eyes, a bad person and bad philosopher. In his book The Ashtray (Or the Man Who Denied Reality), Morris attacks the cult—my term, but I suspect Morris would approve, since it describes a group bound by irrational allegiance to a domineering leader--of Kuhn. “Many may see this book as a vendetta,” Morris writes. “Indeed it is.”

Morris blames Kuhn for undermining the notion that there is a real world out there, which we can, with some effort, come to know. Morris wants to rebut this skeptical assertion, which he believes has insidious effects. The denial of objective truth enables totalitarianism and genocide and “ultimately, perhaps irrevocably, undermines civilization.”

I love Morris’s films, and I love The Ashtray. It is an eccentric as well as deadly serious book, a mixture of journalism, memoir and polemic. It features Morris’s interviews with Noam Chomsky, Steven Weinberg and Hilary Putnam, among other big shots. It is crammed with illustrations and marginalia on all manner of arcana, including pet rocks, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, Borges’s “Library of Babel,” The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Humpty Dumpty, unicorns and the pink fairy armadillo.

These apparent digressions, while entertaining in their own right, serve the main theme. The armadillo, for example, helps Morris make a point about the evolution of scientific definitions. A pink fairy armadillo is a pink fairy armadillo, whether defined by its DNA or morphology. Well, duh, you might think. But according to (Morris’s version of) Kuhn, there is no objective reality to which language refers. All we have are words and their ever-changing meanings. We are “trapped in a fog of language with no way out,” as Morris puts it.

This is radical postmodernism, which holds that we do not discover armadillos, electrons or even Earth, we imagine, invent, construct them. Postmodernists can’t say “truth,” “knowledge” and “reality” without smirking, or wrapping the terms in scare quotes. Morris calls Structure a “postmodernist Bible.”

As an alternative to Kuhn’s perspective, Morris offers us that of philosopher Saul Kripke. I’ve listened to philosophers yammer ad nauseam about Kripke’s magnum opus, Naming and Necessity, and I sat in on a seminar with him in 2016. He was frail, confined to a wheelchair, and he mumbled. To the extent that I understood him, I was underwhelmed. Kripke seemed to push philosophical fussiness over definitions to absurd extremes.

Thanks to Ashtray, now I appreciate Kripke’s achievement. He sought to establish that the things to which our words refer exist independently of our conceptions of them. To a non-philosopher that might sound like a truism, but it contradicts the postmodern contention that words and concepts are all we know. Just because we invent words and their meanings, Morris insists via Kripke, does not mean we invent the world.

I agree, to an extent, with Morris’s take on Kuhn. I spent hours talking to Kuhn in 1992, when he was at MIT, and he struck me as almost comically self-contradicting. He tied himself in knots trying to explain precisely what he meant when he talked about the impossibility of true communication. He really did seem to doubt whether reality exists independently of our flawed, fluid conceptions of it.

At the same time, Morris beats Kuhn so viciously that I feel sympathy for him. Morris calls Kuhn a “megalomaniac,” “perverse dictator” and “maleficent deity,” who applied his skepticism to everyone but himself. Being Kuhn’s graduate student, Morris says, was like being the guy in 1984 who, threatened with having his face eaten off by rats, says truth is whatever Big Brother says it is. 2+2=5. (Ironically, Kuhn, in Structure, compared scientists to Big Brother’s brainwashed followers.) I’d like to offer a few points in Kuhn’s defense.

*Postmodernism Is Progressive. Morris proposes that postmodernism is an attractive ideology for right-wing authoritarians. To support this claim, he notes the scorn for truth evinced by Hitler and the current U.S. President, for whom power trumps truth. Morris suggests that “belief in a real world, in truth and in reference, does seem to speak to the left; the denial of the real world, of truth and reference, to the right.”

That’s simply wrong. Postmodernism has often been coupled with progressive, anti-authoritarian critiques of imperialism, capitalism, racism and sexism. Postmodernists like Derrida, Foucault, Butler and Paul Feyerabend (my favorite philosopher) have challenged the political, moral and scientific paradigms that enable people in power to maintain the status quo.

*Questioning Science Is Healthy. Yes, postmodernism can become decadent, questioning even the paradigms that underpin proven science, and social-justice movements. But it serves as a valuable counterweight to our yearning for certainty. Kuhn was right that even the most ostensibly rational thinkers—scientists!—can fool themselves into thinking they know more than they really do.

Scientists often cling to paradigms for non-scientific reasons. (In fact, that is a major theme of my book Mind-Body Problems: Science, Subjectivity and Who We Really Are.) Kuhn’s model is all too apt for describing modern psychiatry, which often acts like the marketing arm of the pharmaceutical industry, or evolutionary biology, some proponents of which have made excuses for the persistence of racism, sexism and militarism.

*Kuhn, Mysticism and Solipsism. One of the defining characteristics of mystical states—whether spontaneous or induced by meditation or LSD—is that they cannot be described with ordinary language or concepts. During a mystical experience you feel, you know, that you are seeing things as they really are, and yet, paradoxically, you have a hard time describing what you see. God, Truth, Reality, whatever you want to call it is ineffable, as William James put it.

Kuhn would surely be horrified at this analogy, but Structure works as a kind of negative theology, which insists that God transcends all our descriptions of Him. Kuhn's philosophy also captures a profound truth about human existence, that we are all trapped in our own little solipsistic bubbles. Language can help us communicate with each other, but ultimately we can only guess what is going on in others’ minds.

*Does Morris Really Admire Kuhn? Toward the end of Ashtray, as the insults piled up, I began wondering whether Morris is slyly, or perhaps subconsciously, defending Kuhn. Morris’s defense of objective truth makes no pretense of objectivity. His blatantly emotional, biased, over-the-top screed implicitly corroborates Kuhn’s point that truth-seeking is an inescapably subjective endeavor.

Morris conjectures that Kuhn, deep down, knew that he was wrong, and that was why he defended his philosophy so fiercely. Perhaps Morris bashes Kuhn with equal ferocity because he suspects Kuhn was, in some respects, right.

A final point. I’ve long felt that philosophy, when it tries, or pretends, to be rigorously rational and objective, commits a category error. Philosophy is closer to art than to science or mathematics. Philosophy helps us see the world through someone else’s eyes, as a good novel, painting, film or song does.

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche said that “every great philosophy” is a “confession,” a “species of involuntary and unconscious autobiography.” Structure is a great work of philosophy, and so is the book it spawned, Ashtray, which helps us see the world with Morris’s obsessive curiosity.

Morris, who calls his philosophy “investigative realism,” writes, “I feel very strongly that, even though the world is unutterably insane, there is this idea—perhaps a hope—that we can reach outside of the insanity and find truth, find the world, find ourselves.” Kuhn, for all his faults, goaded Morris into writing a brilliant work of investigative realism. For that, if for nothing else, he, and we, should thank Kuhn.

*I added "According to Morris" above after being contacted by Kuhn's son Nat, who has raised questions about the ashtray incident.

Further Reading:

I wrote about Morris’s views of Kuhn in three previous columns: Did Thomas Kuhn Help Elect Donald Trump?, Second Thoughts: Did Thomas Kuhn Help Elect Donald Trump? and Filmmaker Errol Morris Clarifies Stance on Kuhn and Trump.

What Thomas Kuhn Really Thought about Scientific "Truth"

Was Philosopher Paul Feyerabend Really Science's "Worst Enemy"?

What Is Philosophy's Point? Part 1

Jellyfish, Sexbots and the Solipsism Problem

Dear "Skeptics," Bash Homeopathy and Bigfoot Less, Mammograms and War More

A Dig Through Old Files Reminds Me Why I’m So Critical of Science

Everyone, Even Jenny McCarthy, Has the Right to Challenge “Scientific Experts”

Science, History and Truth at the Faculty Club

Mind-Body Problems (free online book)

For alternative takes on Ashtray, see reviews by Tim Maudlin, David Kordahl and Philip Kitcher.