This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

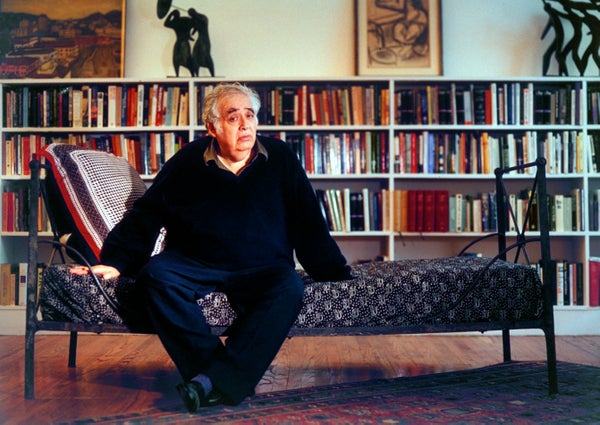

Harold Bloom, the great literary critic, has just died. I read and loved Bloom’s book The Anxiety of Influence in college, and I remembered it years later when I was writing my first book, The End of Science. Although Bloom was writing about poetry, his work helped me understand the anxiety of modern scientists butting their heads against science’s limits. Below is a lightly edited excerpt from The End of Science, in which I explain how Bloom’s ideas apply to science. – John Horgan

Many scientists whom I interviewed for this book seemed gripped by a profound unease, and with good reason. If one believes in science, one must accept the possibility—even the probability—that the great era of scientific discovery is over. By science I mean not applied science, but science at its purest and grandest, the primordial human quest to understand the universe and our place in it. Further research may yield no more great revelations or revolutions, but only incremental, diminishing returns.

In trying to understand the malaise of modern scientists, I have found that ideas from literary criticism can serve some purpose. In his influential 1973 essay, The Anxiety of Influence, Harold Bloom likened the modern poet to Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Just as Satan fought to assert his individuality by defying the perfection of God, so must the modern poet engage in an Oedipal struggle to define himself or herself in relation to Shakespeare, Dante, and other masters. The effort is ultimately futile, Bloom said, because no poet can hope to approach, let alone surpass, the perfection of such forebears. Modern poets are all essentially tragic figures, latecomers.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Modern scientists, too, are latecomers, and their burden is much heavier than that of poets. Scientists must endure not merely Shakespeare’s King Lear, but Newton’s laws of motion, Darwin’s theory of natural selection, and Einstein’s theory of general relativity. These theories are not merely beautiful; they are also true, empirically true, in a way that no work of art can be. Most researchers simply concede their inability to supersede what Bloom called “the embarrassments of a tradition grown too wealthy to need anything more.” They try to solve what philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn has patronizingly called “puzzles,” problems whose solution buttresses the prevailing paradigm. They settle for refining and applying the brilliant, pioneering discoveries of their predecessors. They try to measure the mass of quarks more precisely, or to determine how a given stretch of DNA guides the growth of the embryonic brain. Others become what Bloom derided as a “mere rebel, a childish inverter of conventional moral categories.” The rebels denigrate the dominant theories of science as flimsy social fabrications rather than rigorously tested descriptions of nature.

Bloom’s “strong poets” accept the perfection of their predecessors and yet strive to transcend it through various subterfuges, including a subtle misreading of the predecessors’ work; only by so doing can modern poets break free of the stultifying influence of the past. There are strong scientists, too, those who are seeking to misread and therefore to transcend quantum mechanics or the big bang theory or Darwinian evolution. For the most part, these scientists have only one option: to pursue science in a speculative, post-empirical mode that I call ironic science. Ironic science resembles literary criticism in that it offers points of view, opinions, which are, at best, interesting, which provoke further comment. But it does not converge on the truth. It cannot achieve empirically verifiable surprises that force scientists to make substantial revisions in their basic description of reality.

The most common strategy of the strong scientist is to point to all the shortcomings of current scientific knowledge, to all the questions left unanswered. But the questions tend to be ones that may never be definitively answered given the limits of science. How, exactly, was the universe created? Could our universe be just one of an infinite number of universes? Could quarks and electrons be composed of still smaller particles, ad infinitum? What does quantum mechanics really mean? (Most questions concerning meaning can only be answered ironically, as literary critics know.) Biology has its own slew of insoluble riddles. How, exactly, did life begin on earth? Just how inevitable was life’s origin and its subsequent history?

The practitioner of ironic science enjoys one obvious advantage over the strong poet: the appetite of the reading public for scientific “revolutions.” As empirical science ossifies, journalists such as myself, who feed society’s hunger, will come under more pressure to tout theories that supposedly transcend quantum mechanics or the big bang theory or natural selection. Journalists are, after all, largely responsible for the popular impression that fields such as chaos and complexity represent genuinely new sciences superior to the stodgy old reductionist methods of Newton, Einstein, and Darwin. Journalists, myself included, have also helped quantum theories of consciousness win an audience much larger than they deserve given their poor standing among professional neuroscientists.

I do not mean to imply that ironic science has no value. Far from it. At its best ironic science, like great art or philosophy or, yes, literary criticism, induces wonder in us; it keeps us in awe before the mystery of the universe. But it cannot achieve its goal of transcending the truth we already have. And it certainly cannot give us—in fact, it protects us from—The Answer, a truth so potent that it quenches our curiosity once and for all time. After all, science itself decrees that we humans must always be content with partial truths.

Further Reading:

The End of Science (2015 edition, with new preface)

Was I Wrong about ‘The End of Science’?

The Twilight of Science's High Priests

Why There Will Never Be Another Einstein

See also my free, online book Mind-Body Problems: Science, Subjectivity & Who We Really Are.