This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Lots of sages have suggested that truth and beauty are linked, even in some sense equivalent. A famous expression of this proposition is the finale of John Keats’s Ode on a Grecian Urn: "Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all/Ye know on Earth, and all ye need to know."

I’ve been mulling over this formula since physicist Sabine Hossenfelder spoke at my school this month about her book Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray (see my review here). Many modern physicists, she points out, from Poincare to Steven Weinberg, have touted beauty—which includes properties such as elegance, simplicity and symmetry—as a guide to truth. Paul Dirac wrote: “The research worker, in his efforts to express the fundamental laws of Nature in mathematical form, should strive mainly for mathematical beauty.”

The obvious problem is that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and ideas about beauty vary across eras and cultures. Moreover, allegedly beautiful ideas turn out to be false. Ancient Greek philosophers, to whom the circle embodied geometric perfection, assumed the orbits of heavenly bodies must be circular. Wrong.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Some physicists initially rejected the big bang because it is too complicated and messy (not to mention similar to religious creation stories). Critics found the steady state theory, which holds that the universe has always existed more or less in its current form, more elegant and plausible. Wrong again. Other beautiful ideas that experiments failed to confirm include proton decay and magnetic monopoles.

Advocates of string theory extol its beauty, but after 40 years they haven’t produced any empirical evidence for it, with good reason. Scaling up from present technology, it would take a particle accelerator 1,000 light years around to detect a string. Our solar system is only one light day around. On her blog “BackReaction,” Hossenfelder notes that relying on beauty

has sometimes worked, and sometimes not. It’s just that many theoretical physicists prefer to recall only the cases where arguments from beauty did work. And in hindsight they then reason that the wrong ideas were not all that beautiful. Needless to say, that’s not a good way to evaluate evidence. Finally, the use of criteria from beauty in the foundations of physics is, as a matter of fact, not working. Beautiful theories have been ruled out in the hundreds, theories about unified forces and new particles and additional symmetries and other universes. All these theories were wrong, wrong, wrong. Relying on beauty is clearly not a successful strategy.

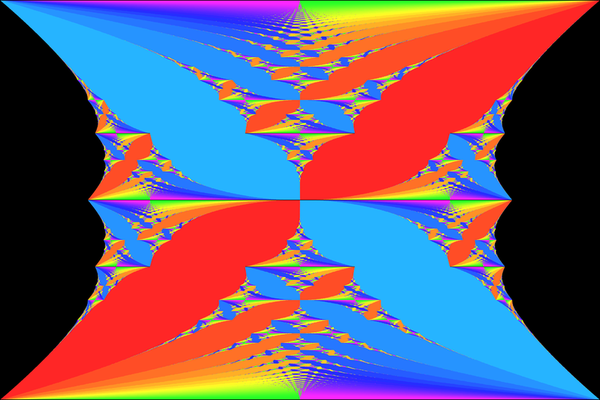

Polymath Douglas Hofstadter raised another objection to the linkage of truth and beauty when I interviewed him for my book Mind-Body Problems. Ironically, I had been struck by the artistry of his books Gödel, Escher, Bach and I Am a Strange Loop and the beauty of his “strange loop” model of the mind. As a physicist, Hofstadter discovered a strikingly beautiful pattern, now called Hofstadter's Butterfly, generated by electrons (see image). During our conversation, he kept raising aesthetic issues, for example explaining why he left particle physics in the 1970s.

“I became more and more lost and repelled by the ugliness of theories that I was seeing,” Hofstadter said. “I just could not stomach any of it.” I assumed Hofstadter would be sympathetic to Keats’s “Beauty is truth” line. But when I mentioned it, Hofstadter snorted in disgust. Here is how I describe our subsequent exchange in my chapter about him, “Strange Loops All the Way Down”:

“That’s nonsense,” Hofstadter said [about truth is beauty]. “Absolute junk. That’s the opposite of what’s true. I hate that phrase.” He was so vehement that I started laughing. “Germany killed six million Jews,” he said, scowling. “That’s true. Does that make it beautiful? Come on. Nonsense.” I wasn’t laughing now. But your writing is so beautiful, I said, to mollify him, and because it is true.

“I think we should try to bring as much beauty into the world as we can,” he said, “since the world is so non-beautiful!” He seemed genuinely furious. But, but, I sputtered. Your writing draws attention to these beautiful, deep structures—in music, mathematics, in our selves.

“Hitler had a self, but not a beautiful one,” he retorted. Not every strange loop “is a beautiful thing that gives rise to beauty in the world. It can give rise to mass murderers and serial killers and rapists.” Hofstadter saw the world as “filled with anguish.” During the course of evolution, “trillions of creatures have suffered at the hands and claws of others. I don’t think of that as beautiful in any way, shape or form, I think of it as horrible.” He called evolution “horrendous,” “ruthless,” “violent.”

Fortunately, some humans are capable of recognizing and overcoming this natural violence and cruelty. He chose at an early age not to eat animals or wear pieces of them, and he strives to be kind to people. “I see the world as being the site of tremendous pain. But for that very reason I think it’s very important to try to be gentle and kind and empathetic and compassionate, and to help suffering people. Because the world is so cruel and merciless.”

In other words, truth is often repulsive, morally as well as aesthetically. Elsewhere in Mind-Body Problems, in a chapter on philosopher-novelist Rebecca Goldstein, I suggest that the arts might be a better route to self-understanding than science. But artistic beauty can lead us astray. That is why Plato wanted to exclude poets from his utopia.

Decades ago I saw Triumph of the Will, the Leni Riefenstahl documentary about a Nazi rally. Rationally, the film repulsed me. Viscerally, Riefenstahl’s beautiful music and imagery stirred me. When Hitler (a former artist!) hailed the hordes of adoring, gorgeous men, women and children, part of me wanted to jump to my feet and cheer.

Humanities professors preach that great art makes you a better person, but that, like many platitudes we professors spout, is false. Stalin was an avid reader of literature, including poetry. He once told a group of writers, “The production of souls is more important than the production of tanks.... And therefore I raise my glass to you, writers, the engineers of the human soul.” By the time he died, Stalin had slaughtered almost as many people as Hitler.

Both these tyrants thought they were creating good, beautiful societies. So what’s my point? Life is ugly as well as beautiful, bad as well as good, and the path to truth—especially the truth about ourselves--is fraught with peril.

Addendum: Philosopher Gregory Morgan, my friend and colleague, has written a fascinating paper about beauty and scientific truth, "The Value of Beauty in Theory Pursuit: Kuhn, Duhem, and Decision Theory." Should judgments of beauty play a guiding role in theoretical science even if beauty is not a sign of truth?" Morgan asks. "In this paper I argue that they should in certain cases." Check out his argument here.

Further Reading:

Can Science Solve-Really Solve-the Problem of Beauty?

See my 2016 Q&A with Hossenfelder as well as my interviews with other truth-seekers: Scott Aaronson, David Chalmers, David Deutsch, George Ellis, Marcelo Gleiser, Robin Hanson, Nick Herbert, Jim Holt, Stuart Kauffman, Christof Koch, Garrett Lisi, James McClellan, Priyamvada Natarajan, Martin Rees, Carlo Rovelli, Rupert Sheldrake, Lee Smolin, Sheldon Solomon, Paul Steinhardt, Tyler Volk, Steven Weinberg, Edward Witten, Peter Woit, Stephen Wolfram and Eliezer Yudkowsky.