This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Take a moment and try to remember the last bird that you saw. When was it? Last week? Five minutes ago? What did it look like? What kind was it? Maybe you knew the answers right away, but I certainly didn’t. The Birds in Your Schoolyard after-school program is opening the eyes of 5th-8th graders not just to notice the birds around them, but to contribute to one of the largest ornithology databases in all of citizen science.

The program curriculum takes place over a dozen sessions and includes activities ranging from role-playing games testing various beak types to a chance to design your own bird. And every session has a chance to go out and collect data. Carla Stough-Huffman, Coordinator for Professional Development at Greater Rochester AfterSchool Alliance, ran the program last spring and couldn’t help but feel a personal connection. Stough-Huffman grew up in a rural environment, but she has spent the last 26 years living in an urban setting. For her, anything that called people to form stronger connections with their natural surroundings was a welcome opportunity.

Science Action Club at East Syracuse Minoa Central School District. Credit: Windy Cardarelli

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Stough-Huffman was actually shocked that some of the adults she interacted with did not believe they could even run the program in Rochester in the spring semester, because “birds don’t come out in the winter.” It took her a while to realize that they weren’t kidding. Kelly Schaeffer, from the Education Department of Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology, referred to the phenomenon as “bird blindness.” Without a reason to notice the animals in their surroundings, many people just don’t.

Schaeffer said that this lack of awareness is one of the reasons she loves eBird, the program that Birds in Your Schoolyard uses for its citizen-science component. “Participating in citizen science takes the blinders off,” she explained. “It gives them a reason to look.” The eBird program started in 2002 and has since become a massive resource for data about bird populations. Schaeffer said that more than 1/3 of a billion entries have been made, with observations accounting for 99% of all known bird species in the US. The database is open for anyone to access and use. It also provides an important complement to the more labor-intensive and expensive use of satellite trackers. Schaeffer is so enamored with the dataset that the map of all global participants serves as her desktop background.

But many adults, let alone middle schoolers, may not feel confident enough in their ability to identify birds to feel comfortable contributing to such a database. After-school programs provide an important chance to overcome that kind initial hesitation. Giving kids a chance to get the basics, and ignite an interest, opens doors to activities that they can take part in long after the end the program itself. Some programs use multiple approaches to get participants up to speed. Birds in Your Schoolyard combines written materials and hands-on activities with use of the Merlin bird-identification app. Taking a few moments to select the size, predominant colors, and behavior of your bird from onscreen options yields a series of full-color images targeted for your location and time of year. Suddenly the idea of honing your future bird-identification skills seems a little more manageable.

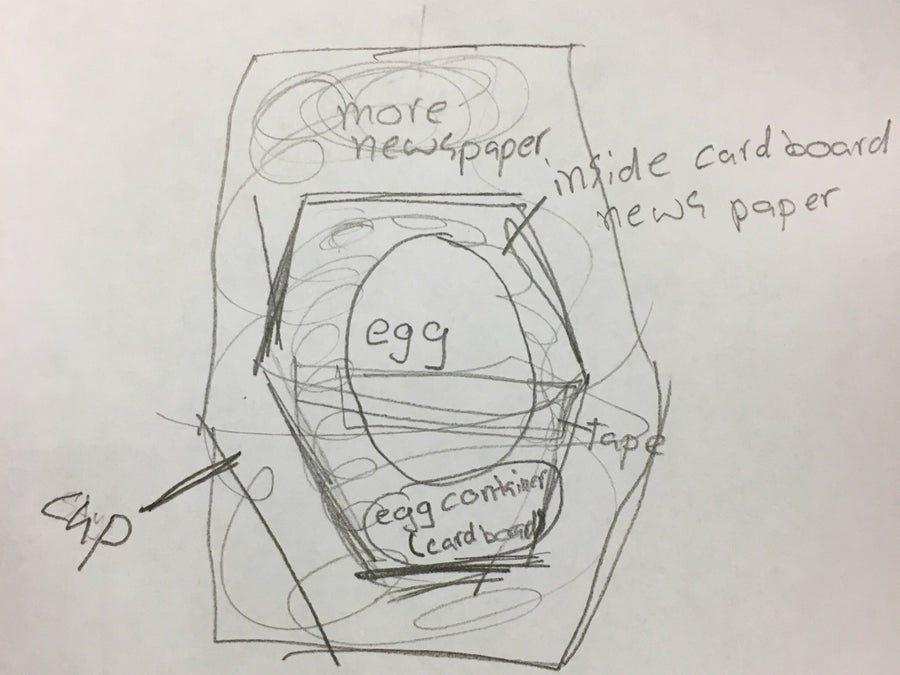

Designing a structure to protect eggs during a fall. Science Action Club at East Syracuse Minoa Central School District. Credit: Windy Cardarelli

Stough-Huffman and Schaeffer both felt that one of the factors commonly holding educators back from leading certain afterschool STEM programs is a lack of confidence in the material itself. Stough-Huffman felt that the Birds in the Schoolyard program was particularly well-designed, with both the educator and the students in mind. Educators had the resources to explain and field questions, and students got to engage with the material in a variety of ways. Building and flying paper planes helped them to understand wing design and flight styles from eagles to owls. Trying to get various food sources (juice, beads, etc) out of cups with different beaks (straws, chopsticks, etc) let kids learn about adaptation. They even got to put their art skills to work deigning a bird with specific features to match its environment.

Students would have a chance each session to look for birds to log for eBird on the playground or through the windows. On rainy days, kids had a chance to use some extremely novel technology: binoculars. For many of the kids, binoculars were more exotic and exciting than the teacher’s iPad. And once the kids had opened their eyes to the birds around them – yes, even in winter – there was no stopping them. Stough-Huffman said that some students who did not have internet access at home would come in with details wanting to figure out which “huge bird” they had seen over the weekend.

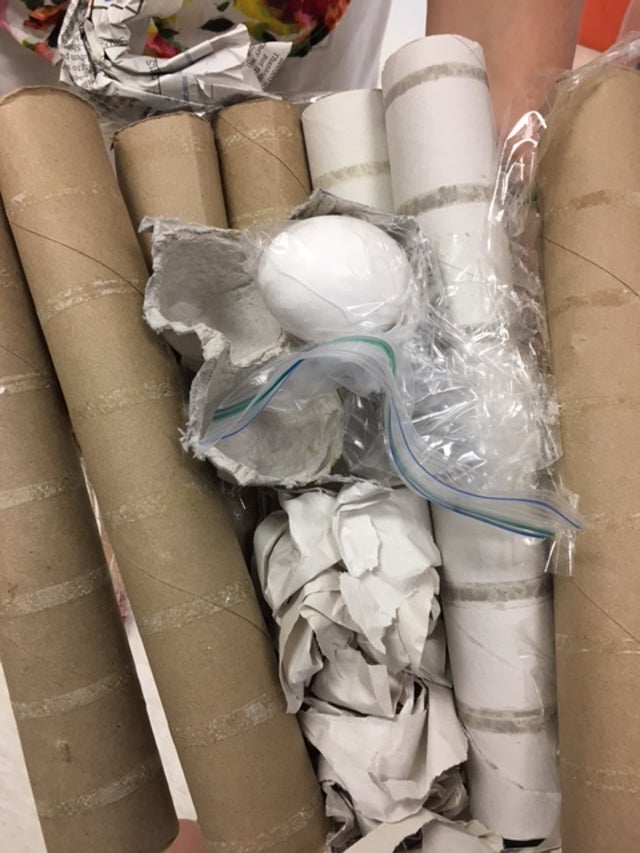

Success! A safe egg! Science Action Club at East Syracuse Minoa Central School District. Credit: Windy Cardarelli

Windy Cardarelli, an educator with East Syracuse Minoa School District, co-teaches in classrooms and works with special education students. For her, implementing after-school programs often means working in schools with 65-70% at or below the poverty level and with student populations whose needs may leave them unable to read or write. Cardarelli was inspired by the buy-in from her students. Taking part in the varied activities of this program and contributing to the eBird database made them part of something important – something scientists would use. They would walk down the halls with pride and tell adults in the building, “I am a citizen scientist!”

When talking about ways that similar programs could grow in the future, all three women shared the desire to bring in a local bird watcher to talk to the group. This could not only show students the potential for carrying these skills through their lives, but also provide another resource for their polishing bird identification. Whatever the future programs look like, for birds or bugs or otherwise, finding a way for well-designed activities to take the blinders off makes it possible to start life-long connections to whatever natural environment a student may be in.

***The Birds in Your Schoolyard Program has since been renamed Bird Scouts and is organized by the National Girls Collaborative project, the California Academy of Sciences, the New York STEAM Girls Collaborative, and the Network for Youth Success.***