This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Author’s note: This is the latest post in the Wonderful Things series. You can read more about this series here.

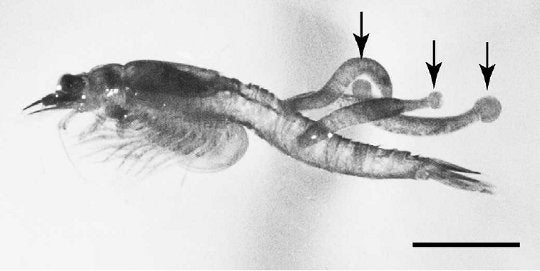

Opossum shrimp leeches combine three concepts that do not seem to belong together into one awesome parasite -- a parasite that also happens to be one-quarter of the size of its host:

Scale bar 5 mm. Fig. 3 from Burreson et al. 2012. Click here for source.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In human terms, this would be a parasite the length of your lower leg. It’s definitely a drag for the opossum shrimp.

This is an opossum shrimp:

"Hemimysis anomala GLERL 4". Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

Opossum shrimp get their name from their habit of brooding their non-swimming larvae in a special pouch, and from their obvious resemblance to shrimp. They are not, however, actual shrimp.

There are only two species of the ambitious leeches who target them. The first described species – Mysidobdella borealis -- was discovered on opossum shrimp around the Arctic and North Atlantic Ocean around Spitzbergen, the White Sea, the Kara Sea, Greenland, and as far south as New Jersey and France. The newer of the two species – Mysidobdella californiensis -- was discovered, not surprisingly, off the coast of California. A freak event led to its discovery: a bloom of opossum shrimp – also called mysids – in 2010.

For reasons not understood by anyone, in the summer and fall of 2010, the population of opossum shrimp in the Pacific off California exploded, an event that biologists perhaps euphemistically termed a “reproductive swarm”. At the Bodega Marine Laboratory in Bodega Bay, California, so many mysids appeared that they were sucked into the filtration chambers of the lab’s water clarification system. The staff, making the most of the windfall, simply collected them for fish food.

However, the staff, ever observant, happened to notice something … odd. Some of the mysids were sporting rather large groupies. The staff made “additional efforts” to collect opossum shrimp with hitchhikers directly from the filters. They succeeded on only one day over the next two weeks, but that was enough to seal the deal.

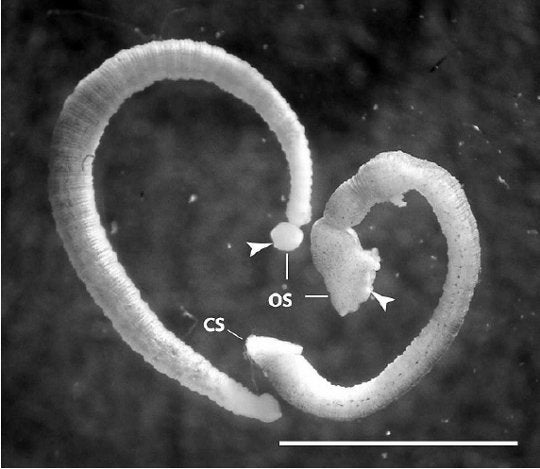

Both species of opossum shrimp leech look a bit like a skinny cheese doodle surmounted by an “oral sucker”. The new species, M. californiensis, has a much larger and more “deeply cupped” oral sucker than M. borealis.

M. borealis, left, and M. californiensis, right. 0s= oral sucker, cs= caudal sucker. Scale bar 5 mm. Fig. 4 from burreson et al. 2012. Click here for source.

They also have tail suckers, and M. californiensis’sis also about twice the size of M. borealis’s.

It’s likely these leeches are parasites specific to opossum shrimps. In one of the creepier passages in the text, the authors noted, “In the laboratory, leeches rapidly attached to mysids with the oral sucker upon contact and then shifted to a position dorsally or laterally on the cephalothorax or abdomen.” Have I mentioned lately how much I love my fingers and thumbs?

Additionally, no fish red blood cells have been found in their guts. On the other hand, mysid hemolymph (blood) has not yet been confirmed in their gut either. M. borealis also apparently turns its nose up at every local fish it’s been offered, and like M. californiensis, loves to cuddle with mysids. Strong circumstantial evidence, but circumstantial nonetheless.

Although these opossum shrimp leeches are the only marine leeches strongly suspected to parasitize invertebrates, marine leeches are apparently commonly found on lots of other inverts. For these other invertebrates, picking up a marine leech seems to be likliest in sand and mud.

However, these leeches are not parasitizing the arthropods they shack up with there; they have never been found to suck their hemolymph either. Instead, they seem to use their shells as a surrogate floor on which to anchor themselves or attach a cocoon, a leech egg case. The leeches’ true victims are fish or sea turtles in the surrounding waters, who no doubt wish their parasites would follow the example of the opossum shrimp leeches, and see the real appeal of shrimp sushi.

Reference

Burreson, Eugene M., Bernard Kim, and Julianne Kalman Passarelli. "A New Species of Mysidobdella (Hirudinida: Piscicolidae) from Mysids along the California Coast." Journal of Parasitology 98, no. 2 (2012): 341-343.