This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Among the many criticisms of the present administration is that tours of the White House have been suspended well into the presidential term. (Previous presidents reopened the White House with a week or so of assuming residency.) While tours have been suspended during wartime and were also famously suspended by the Secret Service during the Obama administration in response to the 2013 sequester challenges, the current closure is particularly noticeable given the restrictions against the press and the current climate concerning trust and information in general. Following Congressional pressure—as they manage and approve constituent requests—the White House has since announced that the tours would resume on March 7th. Where did this practice of opening the White House come from and why is it so important to the democratic process?

There is a scene in Steven Spielberg's Lincoln where Mr. and Mrs. Jolly obtain an audience with President Lincoln to petition a claim. There is nothing remarkable about Mr. and Mrs. Jolly. They're not politicians or celebrities; they are simply citizens from Missouri who waited their turn in line to speak with Lincoln and ask his help in mediating a dispute. At one point in the scene, the door to Lincoln's office opens to a full corridor of clamoring constituents. Such was the norm until visitation procedures was formalized following WWII: anyone could visit the White House, stroll the lawns, and potentially speak with the President himself.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

John and Abigail Adams became the first residents of the unfinished White House in 1800. It had six livable rooms and they brought four servants with them. The Adamses found the house to be drafty, and Abigail had to use the East Room to hang her laundry. Today the White House has 132 rooms and requires a staff of about 90 to keep things running—it also has indoor plumbing and electricity, which its residents did not have access to until 1833 and 1891 respectively. Another major difference from the early White House compared to today is access: It wasn't uncommon for citizens to wander the grounds and early events were designed to encourage public participation. It was a hallmark of the young democracy that its citizens would have direct access to its leaders. The White House was conceived to be representative of the power of the people, after all. It was meant to be an international symbol of democracy. The importance of public access is made apparent in that as sparsely furnished and incomplete as the house was, the Adamses still managed to hold a reception on New Year’s Day in 1801 in the the Ladies Drawing Room. This act set the precedent for entertaining the public in the executive space.

The Jefferson administration established the tradition of an "open house." The White House would be open to the public following the inauguration of a new president, on New Year’s Day and the Fourth of July, as well as for various dinners and the official dignitary events. It was sometimes a surprise to visiting European state leaders to find themselves in the company of well-dressed but otherwise ordinary Americans. It was Jefferson who hosted the first Fourth of July celebration at the executive mansion. He welcomed everyone from citizens to diplomats to Cherokee chiefs and held a festival that included horse races, cockfights and parades of the militia.

One of the wilder stories concerning the public's behavior at the White House is tied to Andrew Jackson's inauguration in 1829. He was a popular candidate and his election drew an estimated 20,000 people to the inaugural festivities. The president delivered his inaugural address from the steps of the Capitol where a crowd control cable broke and the crowd surged forward. Jackson's team pulled him back to the Capitol, but he soon sought out his own horse and rode for the White House. There he found another crowd, which had gathered for the Inaugural Open House. The citizens would wait to congratulate the president, shake his hand, and enjoy some refreshments. The White House had not planned for Jackson's popularity, however, and the crowd was larger than anticipated. Accounts disagree (see here and here) on the extent of the damage done by the crowd, but there seems to be have been some degree of breakage and spillage. Jackson found himself pressed against a wall at one point during the event due to the sheer volume of bodies in the space. He slipped out and spent the night in a hotel while his staff moved the festivities onto the lawn and eventually ushered everyone out.

Incidentally, later in his presidency, Jackson received a 1,400 pound wheel of cheese from a dairy farmer from Sandy Creek, NY. Jackson gave copious amounts of cheese to his friends, but still found himself with a sizeable portion of the gift as his term wound down. His solution was to hold one last open house and make the cheese available to his guests. He hosted an estimated 10,000 people who made short work of the remaining cheese. Unfortunately, part of the collateral damage was that his guests ground bits of cheese into the carpet. The smell lingered for some time.

Despite the challenges of having the public within reach, many presidents felt it was their duty to entertain their citizens. Lincoln said of his time with petitioners, "I feel—though the tax on my time is heavy—that no hours of my day are better employed than those which bring again within the direct contact and atmosphere of the average of our whole people." The open house tradition was curtailed following several assassination attempts and the New Years tradition was ended by Herbert Hoover who had to shake 6,000 hands following his reception.

Today access to the White House is heavily managed, but remains a right of the American people. Visitors need to be approved by their Congressional representative, undergo background check, and then must wait in line for additional security clearance the day of their visit. Still, events like the Inaugural Open House (which was reinstated by by George H.W. Bush), the Easter Egg Roll, dinners, and other events remain important ways of reinforcing the concept of our democracy as something that is of and by the people. The longer the White House remains closed, the longer it is indicative of a government that is not working at its peak.

Have you visited the White House? Comments have been disabled on Anthropology in Practice, but you can always join the community on Facebook. Come tell us all about it.

--

Referenced:

From The White House Historical Association:

Additional Sources:

--

You might also like:

--

Image Credit:

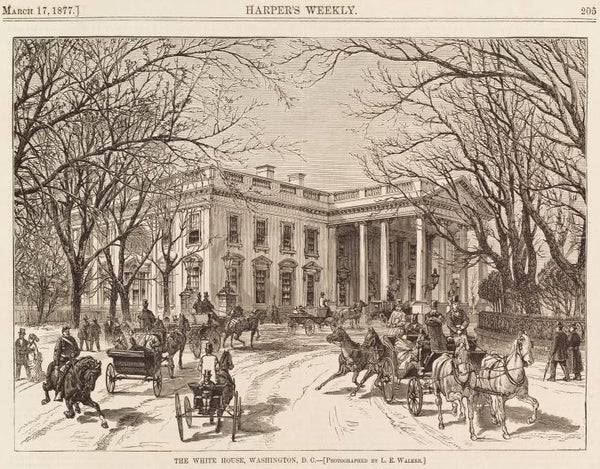

General Research Division, The New York Public Library. "The White House, Washington, D.C." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1877-03-17. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/94295086-e399-7335-e040-e00a18064218