This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The Cemetery of the Innocents in Paris was one of the most well known in the city and its grounds were in high demand by those wishing to be buried in a Christian graveyard between the 12th and 18th centuries. While many couldn’t afford an actual plot, the majority of corpses ended up in mass graves that held around 1,500 people in each. As the corpse count climbed, several problems arose such as over crowding, putrid odors, and the supposed ability of the air in the cemetery to change the color of fabric and rot meat before one’s eyes.

Further, the bodies were not decomposing as expected. For a body to fully decompose, oxygen must be present. In the case of the bodies from the Cemetery of the Innocents, the lack of enough oxygen left the bodies as mounds of fat.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

All of this led to a decree by King Louis XVI in 1775 to close all cemeteries within Paris. It took five years for the order to pass, as the church was unhappy about losing the revenue gained from plot-seekers. Eventually, the bodies were exhumed and moved to underground mine shafts—better known today as Paris’s famous Catacombs.

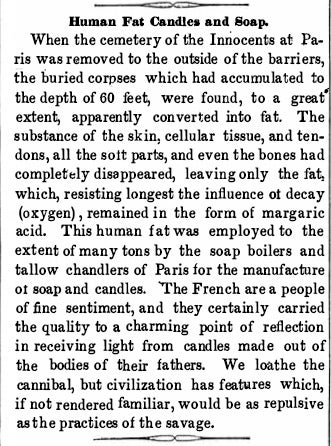

I’m sure by now you’re wondering what this has to do with Scientific American. In the October 30, 1852, issue, the magazine ran an article describing what was done with the fat deposits left behind from the improperly decomposed corpses in the cemetery—they were turned into soap and candles. Although there were no accompanying illustrations with the article, I’ve pasted it here 1) so you can form your own mental image, and 2) so it is clear that I didn’t make this stuff up.