This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

“The wave of hysterical rejoicing that swept over the United States when our president announced the signing of a truce had many impulses” (Scientific American, November 30, 1918, p. 432). The end of the war meant the beginning of reorientation from a vast war footing to one of peace. And if patriotic duty was the social driver during the war, optimism was the hallmark of the aftermath—tempered by reflections on the destruction caused by the war

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 foreshadowed the Great War of 1914–18. Armed forces of two industrialized countries wielding advanced weaponry engaged, and the Empire of Japan won handily. Japanese soldiers and sailors, displaying much courage, enterprise and dash, had dragged heavy artillery guns across land and unleashed a rain of shells on the Russian city of Port Arthur on the southern tip of Manchuria, sinking ships and smashing fortifications. The next year a ship-borne Japanese wireless transmitter led to the interception and annihilation of a Russian fleet at the Battle of Tsushima. The European Powers took notice, and came to the conclusion modern wars were short and winnable by using advanced weaponry, advanced communication, and above all, instilling in soldiers a sense of dash, pluck and élan, or vigor. The stage was set to pour massive numbers of troops into battle, where all sides had highly destructive weaponry manufactured in huge quantities.

A cigarette advertisement from April 5, 1919, in the pages of Scientific American (we allowed tobacco ads back then) co-opts widespread postwar euphoria as a marketing tool. Credit: Scientific American, April 5, 1919, page 36

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The causes of the First World War, as far as this magazine was concerned, were “German militarism” while they were “planning aggression” (November 30, page 432). Unfortunately, propaganda and self-justification runs strongly as a theme through much wartime and postwar literature—including in this magazine, which hewed to a standard U.S. interpretation of German behavior and “atrocities.” (You have to admit, torpedoing the civilian ship Lusitania was pretty bad...then again, transporting ammunition on a civilian ship in the middle of a war—even if it was technically legal—was not looked upon kindly by those destined to be on the receiving end of that particular cargo.)

The literature on the war is vast, but for me the best book on the causes of the Great War is The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, by Christopher Clark (Harper, 2013), which describes the bellicose atmosphere on all sides as well as the muddled diplomacy and failed leadership: “We need to distinguish between the objective factors acting on the decision makers and the stories they told themselves and each other about what they thought they were doing and why they were doing it.”

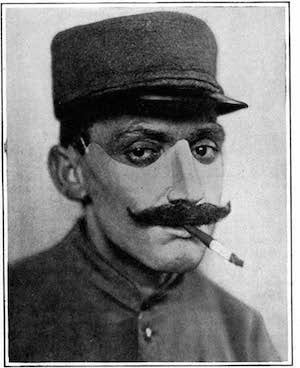

A French soldier with severe wounds from shrapnel wears a facial prosthetic created by an American artist working in Paris, Anna Coleman Ladd. Credit: Scientific American, April 27, 1918, page 383

The technology of war occupies a huge portion of our articles related to the Great War. In blogs, our pages and in our Archive you can see the growing importance of the technology and manufactures of war: artillery, the machine gun, rapid-fire rifles, barbed wire, mines and the inventions designed to leapfrog over obstacles: radio, tactical innovations, transportation, flamethrowers, poison gas, airplanes, tanks and zeppelins (which, being lofted by flammable hydrogen, turned out to be not such a great weapon of war). And in these pages, the paranoid, obsessive focus on the submarine—and how to kill it—shows us the importance in modern warfare of production capacity, raw materials and food for the population. There were those in the German high command who thought that with submarines alone they might be able to achieve victory over the Allies by choking off their industrial production and starving out the populace.

By the end of the Great War, the casualty figures were known to be huge—so many people had experienced a loss—but while the war was going on governments were reluctant to tell their civilian populations of the human cost of fighting a war that required so much effort on the part of those civilians. Propaganda became of prime importance to motivate volunteers, conscripts and factory workers. What little real information there was on casualties came in the form of articles on the medical advances used in treating disabled soldiers; also, “shell shock” and “war neuroses” (now called post-traumatic stress disorder) began to be better understood as a war-caused disability.

.jpg?w=350)

Women workers in a Canadian munitions factory. Credit: Scientific American Supplement, March 31, 1917, cover

The war overturned economies around the world. By the end of the conflagration[OK? TO VARY-yep], half of the French and German gross domestic products were being diverted to the war effort. If casualty figures were obscured, there was no hiding from the civilian population the vast upswing in wartime manufacturing—in fact it was celebrated, and business was booming. Scientific American was an early and fervent booster of innovation and the science and economics of mass production.

The scale of military and economic efforts influenced the social landscape. Industries came to rely heavily on women as a significant portion of their workforces, not just as highly paid munition workers but in many industries because so many men had been needed for military service. The social shifts were not lost on the thinkers of the day: “What will become of the army of men, with families to support, when they return from the war and find their places taken by women, and those mostly unmarried? The necessities of the present are laying the foundation for future problems of most serious, far-reaching and revolutionary importance.” (Scientific American Supplement, March 31, 1917, page 200).

This upheaval in society was not capable of being transformed back to a prewar reality when peace arrived. A month after the war ended and demobilization was underway, we published an article titled: “A Place for Every Man: Getting the Jobless Man and the Manless Job Together”—a telling title showing a desire to simply turn back to clock. Elsewhere in the literature I find evidence of a simmering anger at the permanence of the changes. Philip Gibbs, an official reporter during the war, wrote Now It Can Be Told in 1920, where he flings at us this bitter view of the female workforce: “The painted flapper was making herself sick with the sweets of life after office hours in government employ, where she did little work for a lot of pocket money” (page 534). Zane Grey (of cowboy novel fame) lamented the social changes at the home front in his 1922 novel Day of the Beast, where “the indecent dress and obscene dance of the young women could no longer be influenced by the home or the church” (chapter V).

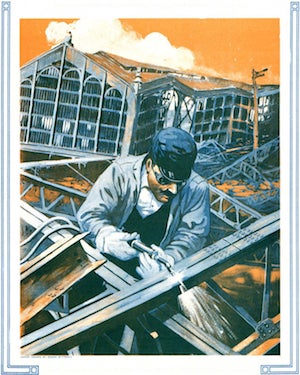

Cleaning up the wreckage of war: a worker in northern France uses an oxyacetylene torch (invented in 1903) to cut up building frames. Credit: Scientific American, March 15, 1919, cover

A hundred years after the war ended, we are still arguing about its cause, whose “fault” it was, the changes worldwide that resulted and how the First World War contributed to the causes of the Second World War. One thing is fairly sure—there are no old soldiers left. Of the 65,038,810 people who served (so says the Encyclopedia Britannica), the last surviving veteran anywhere died on February 4, 2012. She may well have been emblematic of the war: Florence Green served in the British Women’s Royal Air Force, an auxiliary unit originally founded in 1918 to employ female mechanics as much-needed help to maintain that invention so desperately pressed into military service, the airplane.