This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

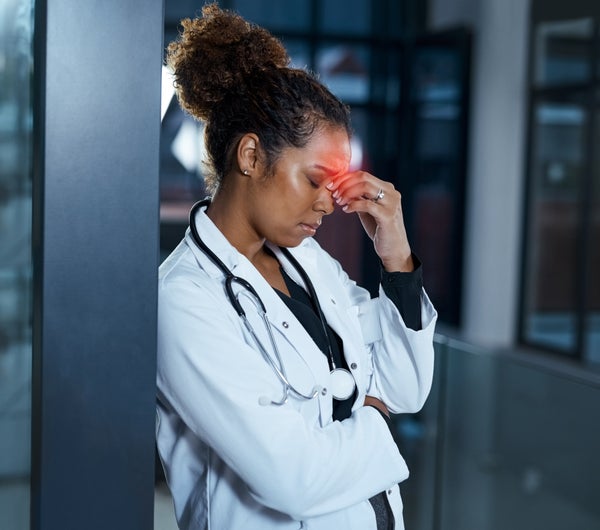

Whether it’s hearing “I’m sure your husband is happy that you keep such a nice body” or being asked why we’re not home taking care of our children, women in medicine constantly face reminders that we do not belong.

On the two-year anniversary of #MeToo going viral, there has been surprisingly little attention to harassment in medicine. If you can’t think of a high-profile doctor who got “taken down” by the movement the way Matt Lauer, Harvey Weinstein, Louis C.K. and Al Franken did, it’s not because harassment isn’t happening in health care. It’s because harassment is the norm.

Gender discrimination is so prevalent in the field that there are currently ongoing lawsuits against major institutions such as Mount Sinai Health System,Oregon Health & Science University and, most recently, Tulane University. But there are virtually no major reported pieces on any of these situations, and there is little public outcry calling for anyone to resign. The reason is that there’s a culture of tolerance in medicine.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As a surgeon, I have seen several talented women physicians be forced to resign as a result of gender discrimination. One was harassed by hospital employees who refused to follow her instructions; she was asked to leave after she expressed concern to her supervisor. In a scenario that’s all too common, another was told—after coming back from maternity leave—that she had not taken care of enough patients and was in danger of losing her job. Other versions of these stories of injustice and harassment are playing out in hospitals across the country.

Women in medicine have to climb over the stumbling blocks of discrimination and harassment throughout our careers. The students I mentor start out with optimism I once had, believing that medicine is a profession of integrity, equity and justice. As they go through their training, however, they see otherwise.

A 2018 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found up to half of female medical students are sexually harassed during their training. And such students are three times as likely as women in non-STEM fields to be sexually harassed

. The report proposed that medicine’s “majority male leadership can, and has, resulted in minimization, limited response, and failure to take the issue of sexual harassment or specific incidents seriously.”

When doctors pursue specialty training after medical school, they continue to see female physicians being treated differently from their male colleagues. A 2017 working paper on referral patterns showed that women surgeons are penalized more harshly for bad patient outcomes than men. Women who have children during training are evaluated more negatively than other trainees. And in written evaluations, female trainees are less likely than men to be described with superlatives such as “outstanding.”

Data from Medscape show that after training, women

are paid far less than men—by $36,000 to $96,000 a year on average—even in female-dominated fields such as pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology. When researchers asked female physicians about maternity leave, they found that just over half of them lose more than $10,000 in income as a result of their leave. And possibly because they usually can’t modify their work schedules before delivery, their pregnancies have higher rates of complications than those of nonphysicians.

To be sure, men can also be targets of harassment. But women, especially minority or transgender women, are far more likely than men to face harassment in the workplace. And in health care, the abusive treatment goes beyond physicians, afflicting nurses, physical therapists, physicians’ assistants and others.

While harassment is unacceptable in any setting, in health care, the consequences extend beyond individual employees to those they care for. Vulnerable sick people deserve to be cared for by experts who can work at the top of their game, unfettered by workplace harassment and discrimination.

Several studies show that patients taken care of by women already have better outcomes than those who are cared for by men. Imagine how much better our patients would do if women didn’t have to combat daily harassment.

Will #MeToo reach the misbehaving men who sit high up in medical schools, using their degrees from elite universities, age and, often, whiteness to shield them against repercussions for their behavior? Will there be a reckoning for the men who take a metaphorical bat to women’s knees, crippling their careers because they are “difficult”? Will there be a time when people of color can express opinions without being labeled as angry or forceful? I’m not sure.

It’s been two years, and many of us have been waiting, hoping that someone would notice what is happening to our nation’s health care workers. TIME’S UP Healthcare, an affiliate of the nonprofit TIME’S UP Foundation, has been banging the drum for the past six months, raising awareness of harassment and inequitable compensation and policies in health care.

But not enough has changed. We need your help. Wherever you live, contact the CEO of the nearest hospital or the dean of the nearest medical school and ask them to become a signatory of TIME’S UP Healthcare. Tell them you care about health care workers and demand safe and equitable workplaces. Demand solutions.

We have to exert external pressure to remove the stumbling blocks of discrimination and harassment in health care. We can’t afford not to. Our very lives depend on it.