This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Moms in science don’t need balance, they need justice. From poor breastfeeding resources to unpaid parental leave, it is clear that policies to support scientist-moms and their families fall far short, especially in the United States. This lack of support leads to significant loss of new moms from full-time science jobs and is one of the drivers of low retention of women and diversity in STEM careers (i.e., the “leaky pipeline”). While enacting policy is a key component of achieving equality, changing our cultural views and expectations around science careers and compatibility with motherhood needs to be part of the conversation.

CAN HAVE IT ALL? OR MUST DO IT ALL?

Being a mother and a research scientist poses unique challenges, because much of our work success is tied to productivity defined by scientific results, scientific papers and research funding. Taking a leave to have a baby can mean a gap in publication record, missed opportunities to apply for funding and participate in collaborations, and delayed promotion. Even when organizations make a conscious effort not to penalize mothers, there are often no clear policies to assess and accommodate early career mothers in science.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

This creates a system where mothers feel pressure to work while on leave to maintain momentum in their career, or work at a more intense rate during late pregnancy (which can have serious repercussions). Women already have to be 2.5 times more productive than their male counterparts to have the same grant success and publication acceptance rate. This already demanding workload collides with the antiquated stereotypes of maintaining an idyllic pregnancy and home life. If we could just work a little harder, we can “have it all.” For many of us scientist-moms, trying to live up to this ideal has led to mental health, marital, and physical well-being complications—and we’re at our wits’ end.

UNCONSCIOUS (AND CONSCIOUS) BIAS

Women in science face unconscious bias, leading to discrimination in hiring and salary. When we become mothers, unconscious bias can become blatant. The double-whammy of unconscious and conscious bias can undermine new moms’ often already hesitant return to the workplace. The motherhood penalty is well known and widespread, where assumptions that moms place family over their career result in workplace discrimination. Female students report having to cope with being discouraged from getting married or having children; women scientists are told that they “had so much potential” when they reveal that they are pregnant, implying that their careers are over; scientist moms are removed from projects without their input because they seem “no longer interested because they had a kid.”

Over and over, mothers are held to a higher standard than others in the workplace, where the blame for project failures and missed deadlines falls on moms and the perception that their work schedule is compromised.

THE OLD BOYS’ CLUB AND OTHER ANTIQUATED STEREOTYPES

Science continues to operate as a network of insiders that influence opportunities for career advancement, where inclusion depends on the adherence to perspectives and values are built on misogyny and prejudice. In academia, this can be represented by the “publish or perish” mantra, and extends to expectations of working long hours and bragging of 60-80-hour work weeks. In this paradigm, there is little room for family commitments, yet this antiquated attitude still forms the context in which modern scientist-moms must operate. The conventional breadwinner/homemaker stereotype also pervades ideas of science workloads. As working mothers, the extra tasks associated with caregiving are often balanced equally with our partners, rather than picked up entirely as they were in decades-past.

This requires a drop in the number of hours at work and a perceived drop in productivity. Importantly, this can extend beyond the workplace to being invited to conference symposia, working groups, and other collaborations that are formed ‘after’ work hours. Moreover, given that maternity leave is federally mandated (in most countries outside the US), but paternity leave is generally not mandatory, our culture clearly delineates who is expected to care for children.

TOXIC GUILT

Women get judged constantly, and its especially apparent when we become mothers. We judge each other for breastfeeding in public, not breastfeeding, not breastfeeding long enough, going back to work too early, staying at home part-time or full-time, feeding our kids nonorganic, store-bought food, sending them to day care, not sending them to day care, bringing them to a conference, leaving them at home. It’s never-ending, it’s exhausting, and it’s toxic.

As scientists, we have all struggled with imposter syndrome at some point in our career, and many of us have struggled with mental health. Adding one or more children to the equation can create profound feelings of ineptitude both at work and at home. Not only can scientist-moms feel unsuccessful in our careers, we can also feel like we can’t succeed at motherhood. The age-old stigma of mothers returning to work can result in feelings of guilt for prioritizing career goals over extended maternity leave.

FROM WORK-LIFE BALANCE TO WORK-FAMILY JUSTICE

In her recent book Making Motherhood Work, Caitlyn Collins coins the term “work-family justice,” which shifts the onus of finding harmony between career and home life from the individual to society. Collins’s book provides increasing evidence that the “work-life balance” phrasing puts the blame on working mothers; a “balance” suggests that moms’ stress is a result of our own shortcomings and mismanaged commitments. It raises the question, why are individual mothers responsible to make this balance work, to figure it out for themselves?Work-family justice stresses that the conflict between work and family is not an inevitable feature of contemporary science careers, and it’s not the fault of women or parents.*

To achieve work-family justice for scientist-moms is to create a system where everyone has the support necessary to be successful in science and family care. We, as a society, need to support each other and develop systems that allow women to succeed as mothers and research scientists.

CHANGING THE CULTURE

How do we start to chip away at the old ideals and pave the way for work-family justice? Changes in policy and legislation are an obvious answer. Laws reflect and are reflected by our cultural values; and with the lowest levels of parental leave in the industrialized world, the United States sends a strong negative message to working mothers.

Embracing work practices that acknowledge dual roles, practices like paid maternity leave, subsidized childcare, on-campus nursing resources, flexible tenure clocks and funding schedules, mandated consideration of gaps in resumes, and conference support, will make it possible for scientist-moms to keep momentum in their research programs while raising children.

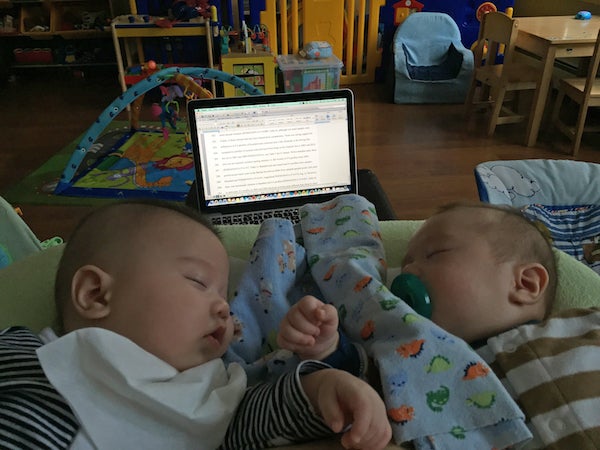

Shiway Wang edits her PhD dissertation with twins in post-nursing coma. Credit: Shiway Wang

How can we start to motivate change as laws slowly catch up? Let’s start by supporting each other, as individual scientist-moms and as a society. As a scientific community, we need to understand that by holding each other down, through toxic guilt, unconscious bias and allowing old ideals to go unchecked, we are not elevating ourselves as a whole. Work-family justice advocates that we support what works for families, acknowledging that we don’t all fit into the same mold.

All science moms wear two hats, often at the same time. Allowing women scientists to be ourselves, to be the scientists that we were (and still are) before we had kids, allows us to fully contribute to STEM through research, teaching and leadership across diverse themes across science, which we believe will improve retention of moms in STEM.

WHAT CAN WE DO TO PROMOTE WORK-FAMILY JUSTICE?

Be less judgy. We can all do this, and we all need to do better. Respect other people’s choices, and share positive experiences through conversation, rather than imposing solutions that worked for you on others.

Be a role model. There are plenty of role models for young mothers in science, including those that have moved away from a competitive and toxic science work environment, to instead focus on fostering young parents in STEM.

Don’t make assumptions. Assuming that moms are no longer interested in particular projects because of family commitments can be harmful. If in doubt, ask. There can often be opportunities to make project logistics work for parents.

Make it obvious that leave won’t be penalized. Provide clear guidelines on leave requests, sick/holiday/vacation leave, and return-to-work policies to facilitate planning ahead. Make exceptions on post-PhD time limits for grants and scholarships which can be particularly harmful for early career moms.

Change the culture. Support flexible work hours and telework options, hold meetings during working hours only, offer live-streaming of seminars and conferences to allow remote participation by scientist moms. Incentivizing equal paternity and maternity leave can help create a culture where partners are expected to participate in childcare. Encourage a culture of efficient work during work hours only and respect for personal time.

Grant programs such as National Geographic Society’s Expand the Field Support for Women and Dependent Care—which helps provide support for women and their families to travel into the field or for childcare to support field work—are an excellent first step and should be adopted more widely by national funding agencies. The allowance of childcare costs in regular research grants, which National Geographic Society has also instituted, is another huge step forward that should be implemented by more funders.

*Editor’s Note (1/7/20): This paragraph was edited after posting to acknowledge Caitlyn Collins’s contributions to the topic discussed.