This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

This year marked the passing of some of our most beloved cultural icons—from David Bowie, Prince, and George Michael to Harper Lee, Gwen Ifill, and Zaha Hadid. But we also lost the developer of the first effective treatment for sickle cell disease, the co-discoverer of dark matter, and the creator of a 3-D printer that spits out living cells as "bio-ink."

Now in its fourth year, this annual remembrance of notable women in the sciences lost in the past 12 months highlights 10 individuals who made indelible marks on their respective fields. At a time when scientists in general are too often overlooked for their crucial contributions to society, it bears noting that high-achieving women in the STEM fields often go especially underappreciated. With this in mind, here's a look at some of the stars of science and technology who left us in 2016.

Ann Caracristi

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: NASA Wikipedia

Ann Caracristi, a leading American cryptanalyst—or code-breaker—who served as deputy director of the U.S. National Security Agency, died in January at the age of 94. Caracristi became a cryptanalyst in 1942, during the heart of World War II, and quickly developed a skill for pattern recognition and reconstructing enemy codes. In addition to her technical abilities, Caracristi was known for her work ensuring that colleagues’ secret code-breaking efforts arrived safely at their proper destinations. As an NSA agent, Caracristi was a leader in the early application of computers to cryptanalysis, and she developed a laboratory for studying covert communications. In 1975, Caracristi became the first woman to be promoted to the senior-level rank of GS-18 at the NSA, and in 1980 she was the first woman to be named NSA’s deputy director. That same year, she received the U.S. Department of Defense’s highest civilian honor, the Distinguished Civilian Service Award. She retired from the NSA in 1982.

Suzanne Corkin

Credit: Louis Bachrach

A pioneer in the field of cognitive neuroscience who was best known for her investigation of the famous amnesic patient H.M. (Henry Molaison), Suzanne Corkin died of cancer on May 24 at age 79. Corkin’s connection with Molaison, who lost the ability to create new memories after brain surgery to control epileptic seizures, began during her doctoral research, which she conducted at McGill University under the guidance of neuropsychologist Brenda Milner. Her work with H.M., whom she studied up until and even after his death in 2008, led to the discovery that the brain’s hippocampus is a key site of consolidation of long-term memory. A longtime professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT, Corkin was the director of the Behavioral Neuroscience Laboratory, where she also investigated long-term consequences of head injury in war veterans and the biology behind neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Throughout her career she authored or co-authored some 150 research articles and 10 books.

Yvette Fay Francis-McBarnette

Credit: Earl Owen McBarnette

Known for her groundbreaking work on sickle-cell anemia, Dr. Yvette Fay Francis-McBarnette passed away on March 28 at age 89. Born in Jamaica and raised in New York City, Francis was the second black woman to attend Yale School of Medicine when she enrolled in 1946. After earning her doctorate, she became a pediatrician, with a specialty in hematology or blood physiology. Dr. Francis went on to direct a sickle-cell clinic at the Jamaica Hospital in New York; there, she pioneered the screening and use of antibiotics to treat children with sickle-cell anemia, a condition in which abnormal “sickled” blood cells can block blood flow, lower blood oxygen levels, and lead to severe problems from organ damage to death. By the time a 1993 New England Journal of Medicine article confirmed the efficacy of the antibiotics she’d been using for a decade and a half, Francis had already treated many thousands of individuals through her organization, the Foundation for Research and Education in Sickle Cell Disease. Among her many honors, Francis served in the Nixon administration on an advisory committee on sickle-cell disease.

Ursula Franklin

Credit: Martin Franklin Wikimedia (CC BY 3.0)

One of Canada’s brightest lights, Ursula Franklin—a physicist, pacifist, feminist, and expert in the social impact of technology—died on July 22 at age 94. Born in Germany in 1921, Franklin survived the Holocaust and earned a PhD in experimental physics before immigrating to Canada to pursue materials science and engineering, with a specialty in metallurgy. She would use her knowledge in this area to become one of the co-developers of the burgeoning field of archaeometry, or the application of scientific methods in the analysis of archeological materials. One of her more well-known research endeavors was the Baby Tooth Survey, in which she and colleagues studied how fallout from nuclear testing affected the level of radioactive strontium-90 in children’s teeth. As a social activist, Franklin often put her scientific background to use: In the late 1960s, she advocated for Canada to increase funding for environmental research and preventative medicine instead of spending it on weapons research. “Peace is not the absence of war but the absence of fear,” she quipped. She also, with several of her colleagues, successfully filed a class-action lawsuit against her longtime employer, the University of Toronto, claiming the university profited unfairly by paying female professors less than men with similar qualifications. Franklin received numerous honors in her lifetime, including being named an officer of the Order of Canada.

Katharine Blodgett Gebbie

Credit: Denease Anderson National Institute of Standards and Technology

Named after a famous trailblazing aunt—physicist Katharine Burr Blodgett—Katharine Blodgett Gebbie was a leading physicist in her own right, with a career that began in astrophysics and culminated with principal roles at the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). An expert in stellar spectroscopy and helioseismology, Gebbie started her career as a researcher at the Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics, now known simply as JILA, in Boulder, Colorado. In the early 1980s, after working as a physicist at NBS, Gebbie transitioned her focus toward supporting industry. She joined the NBS's National Measurement Laboratory, where she quickly became a manager and, in just a few years, chief of the quantum physics division. By the time the NBS was renamed the NIST, Gebbie had risen to the level of senior executive and was appointed as founding director of the Physics Laboratory. Under her leadership and guidance, this laboratory developed four Nobel Prize-winning scientists, whom she actively promoted. In 2010, Gebbie was named the director of the Physical Measurement Laboratory (PML), and from 2013 until her death, she served as senior advisor to the NIST and PML directors. Honored with numerous awards and fellowships for her leadership in physics, Gebbie died on August 17 at age 84.

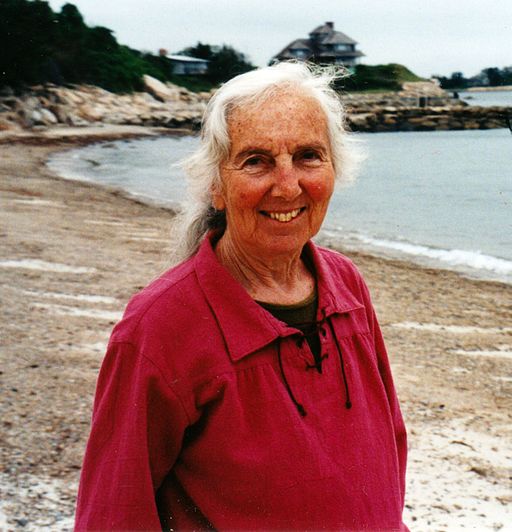

Ruth Hubbard

Credit: Elijah Wald Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

A longtime biologist at Harvard University and a renowned feminist critic of science, Ruth Hubbard passed away on September 1 at the age of 92. As a scientist, Hubbard was best known for her work on the biochemistry of vision: With her PhD advisor—and future husband—George Wald, she helped to elucidate how eyes turn light into information. In particular, Hubbard played a key role in identifying how the eye pigment rhodopsin assists in absorbing light. (Wald would later go on to earn a Nobel Prize for his work on the mechanisms of vision.) After finishing her PhD at Radcliffe College, Hubbard became a full-time researcher at Harvard. But by the late 1960s, she shifted her attention toward the process of scientific inquiry itself. She began studying inequities in the sciences and taught a unique class on the impact of the absence of women in science and medicine. In 1973, under pressure from women's groups at Harvard, Hubbard was finally promoted: She became the first woman to receive tenure in the field of biology. Thereafter, Hubbard established herself as a prominent voice for women and people of color in the STEM fields. She noted in the early 1980s that these arenas were largely comprised of “a self-perpetuating, self-reflexive group: by the chosen for the chosen.” In her later years, Hubbard published several books on the role of women in science, and she remained an activist in support of women until her final days.

Deborah Jin

.jpg?w=250)

Quantum physicist Deborah Jin, an innovator who broke boundaries within the coldest realms of matter, died of cancer on September 15 at the age of 47. Jin, a longtime researcher at JILA and NIST and an adjunct professor at the University of Colorado, participated in some of the earliest studies of Bose-Einstein condensates—states of matter of a gas that exist at just a fraction of a degree above absolute zero, where they display otherwise unobservable quantum phenomena. The development of the first Bose-Einstein condensate, using bosonic matter, led to a Nobel Prize in 2001 for Jin's colleagues Eric Cornell and Carl Weiman and for Wolfgang Ketterle of MIT.

Two years later, Jin accomplished a major feat of her own: She and her team created the first fermionic condensate, a similarly new state of matter involving fermions, the other major type of matter particle. While her work didn’t have direct applications, it nevertheless informed future advances in materials science—such as the possible development of room-temperature superconductors. For her achievements, Jin received many prizes, including the Benjamin Franklin Medal in Physics, the Comstock Prize, and the Institute of Physics Isaac Newton Medal.

Susan Lindquist

Credit: PLoS Wikimedia (CC BY 2.5)

A giant in the field of genetics and one of the world's leading experts in protein folding, Susan Lindquist passed away on October 27 at age 67. Lindquist specialized in the inheritance of proteins: "It has been said that you can't understand biology until you understand evolution. I would argue that you can't understand evolution or biology until you understand protein," she once stated in an interview. Lindquist was known for her founding work on prions, misfolded proteins that can lead to disease—such as mad cow and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease—in mammals.

Among other accomplishments, she showed that changing protein shapes can significantly influence individual organisms; that yeast can be used as a model to study protein-folding and its effects on neurodegenerative disease; and that some protein misfolds may offer valuable evolutionary traits. A professor of biology at MIT since 2001, Lindquist became one of the first women to lead an independent biomedical research firm when she took the helm as director of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research that same year. Most recently, she had returned to the lab, and to her students, who often cited her as a valued mentor. A highly decorated researcher, Lindquist was awarded the National Medal of Science by President Obama in 2010.

Jemma Redmond

At the time of her passing on August 16, 38-year-old Irish biotechnologist Jemma Redmond had made significant strides in the field of 3-D bioprinting—a seemingly futuristic realm in which functioning tissue-like groupings of cells can be created with a specialized 3-D printer. Redmond's vision was already helping firms create complex biological tissues out of "bio-ink," and she had five patents pending for her innovations in creating these tissues from scratch. Chief among these was a printer that could keep cells alive as they were printed. She had also devised a way to print with up to 10 materials at once—a major leap in capability for 3-D bioprinters—and was working to help laboratories bring down the cost of their bioprinting endeavors. In January, Redmond co-founded a company, Ourobotics, to commercialize her work. She had been active in the Irish tech startup scene and had recently won the prestigious Silicon Valley Open Doors Europe competition.

Vera Rubin

Credit: NASA Wikimedia

She was an icon of astronomy whose insights forced us to rethink our place in the cosmos. Her name was perennially floated as a Nobel Prize contender for her research revealing the existence of dark matter. And she was an outspoken feminist, who worked tirelessly to advance the standing of women in science in general and astronomy in particular. On December 25, astronomer and cosmologist Vera Rubin died at the age of 88—but not before she would make revolutionary marks on our understanding of the universe.

A protégé of noted physicists Hans Bethe, Richard Feynman, and George Gamow, Rubin's early observations of galaxies suggested they might be rotating around unseen centers—an unpopular view at the time. Later, her calculations on the motions of galaxies led to what's known as the galaxy rotation problem: Galaxies, Rubin surmised, must contain 10 times more unseen matter than what visible stars can account for in observations. This line of thinking led directly to the currently accepted theory of dark matter, which holds that an unobserved type of matter makes up some 25 percent of the universe's substance, while the visible kind that we know, love, and can detect makes up only about 5 percent (the other 70 percent appears to be made of a force known as dark energy).

For her revolutionary insights, Rubin has been awarded just about every prize and honor available to astronomers, including the National Medal of Science. But the one that eluded her—the Nobel—has become a common point of discussion among science fans each October, as Rubin remains one of the clearest examples of a woman in science who accomplished Nobel-worthy work but who never received a call from Stockholm. With her death, Rubin's name is officially removed from contention, but history will recall her anyway as the discoverer of dark matter.