This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

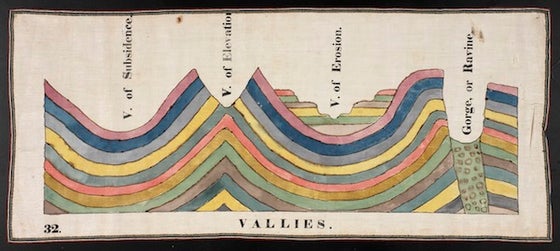

Stripes of yellow, blue, purple, pink and green separated by thin black lines dance in unison across the canvas: dipping down, swooping up, being cut away. A muted and disordered rainbow with four vertical phrases rising from its low points and the single-word title, Vallies, sits below.

Even without a caption, an astute viewer can quickly recognize the crux of the visual argument: not all valleys are created equally. Though indistinguishable from the surface, the layers of rock underground can be arranged quite differently. They can run parallel to the valley floor, or rise and splay open, holding newer layers of sediment which have themselves eroded, or having been cut away steeply. These distinctions are deftly depicted by Orra White Hitchcock, one of America’s earliest female scientific illustrators.

Vallies. Pen and ink and watercolor wash on cotton, with woven tape binding. Credit: Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Currently on view at the American Folk Art Museum, “Charting the Divine Plan: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock (1796–1863)”gives viewers a tantalizing window into the burgeoning scientific world of the 19th century—specifically, the world of illustration. Despite her pioneering status, Hitchcock is, perhaps, under-celebrated. In partial remedy, the exhibition showcases evidence not only of her importance to 19th century science, but also makes clear that her work is still relevant today. In such works as Vallies, she makes her arguments visually with an elegance and economy unimaginable in words. In her oeuvre we see not mere historical artifacts but glimpses of the scientific process as it is still practiced.

The exhibition is organized thematically. Delicate botanical drawings and faded pressings of Massachusetts plants fill a long case. Boldly rendered sea creatures, including hydras, cephalopods, nautiluses and various extinct invertebrates parade across raw cotton in striking gray ink. Dinosaur footprints pace narrow red and blue painted lines on banners above their shale and sandstone–bound fossils. Bright colors and sharps lines reveal the internal order in cross-sections of earth. Interspersed with Hitchcock’s illustrations, there also numerous artifacts, including a schoolbook in which she calculated eclipses in gorgeous script and correspondence with other scientists of her era.

As a girl in Western Massachusetts, Orra White displayed precocious mathematic and artistic abilities and received the best schooling available for either boys or girls. White went on to teach at Deerfield Academy, where she eschewed needlework in favor of instructing her pupils in cartography and botany, assigning the girls to create maps and draw the local flora. While at Deerfield, White met the scientist Edward Hitchcock. Married in 1821, they worked closely for almost 40 years. They went on geological expeditions together. She made original drawings as illustrations for Edward’s publications, including as articles in the American Journal of Science and Arts and the Final Report on the Geology of Massachusetts. She also made vast illustrations on cotton fabric as visuals for the courses Edward taught as a professor of natural science at Amherst College.

In her lifetime, Hitchcock was renowned for her detailed and delicate drawings, which were widely published as etchings, but her many fabric paintings were less well-known — at least beyond Edward’s lecture hall—as Hitchcock considered them “too coarse” for more public display. These fabric classroom charts are striking in terms of scale, material and their loose, simplified treatment.

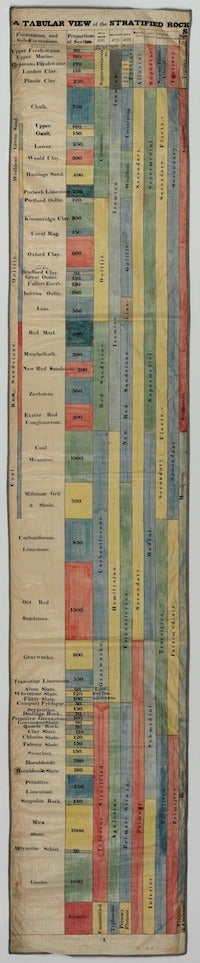

A Tabular View of the Stratified Rocks. Credit: Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

Some illustrations, like A Tabular View of the Stratified Rocks reach 10 feet long. The fabric paintings, with their edges neatly bound in striped, woven cotton tape, are displayed without glass, cleverly fixed with tiny magnets to fabric or plexiglass supports. In the open air the works feel especially lively, as though a lesson on magma veins might commence shortly.

A number of the fabric paintings showcase geology. Some of the illustrations capture particulars, for example the details of a Trap Vein in Clay Slate, Seil, Scotland. Others make more universal statements, as in Trap. After examining many distinct places and accounting for their local features—instances of trap veins, granite veins or coal strata—scientists recognized patterns that allowed them to characterize general geological features. These illustrations attest to moments in the production of scientific knowledge, the movement from particular to universal that is the essence of creation of a theory. Creating concrete visualization from abstracted concepts is a final, vital step in the scientific process and one of Hitchcock’s great strengths. To see her work as merely illustration would be to forget the primacy of visual information in science.

Furthermore, Edward noted her importance, as did his colleagues. In a letter to Edward, a collaborator “presume[s] the map [Edward sent] owes its delicacy & beauty to a hand more delicate than yours or mine” and sends his “respects to Mrs. Hitchcock whom I cannot but regard as a coadjutor.” Though their careers were inextricable, Orra White Hitchcock was not an accessory to her husband’s work but rather his intellectual partner.

The exhibition is small, satisfying, and argues for a place in our modern imagination for this pioneer of scientific illustration.

“The Art of Orra White Hitchcock” is on view at the American Folk Museum’s Lincoln Square location through October 14 and admission is free. The exhibition was organized by the American Folk Art Museum, New York, in collaboration with the Archives & Special Collections, Amherst College; it acknowledges a debt of gratitude to the pioneering work of Daria D’Arienzo and Robert L. Herbert, whose in-depth research on Orra White and Edward Hitchcock was the foundation for their 2011 exhibition and the publication Orra White Hitchcock: An Amherst Woman of Art and Science.