This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

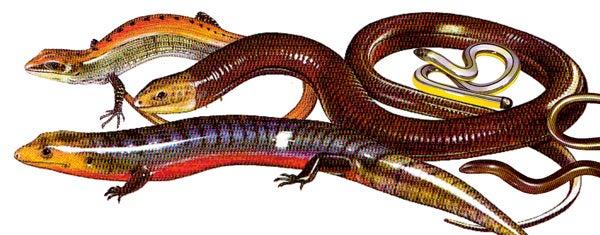

Montage of Alan Male's 1983 illustrations of anguids (with bonus Anniella thrown in too). We're interested in the big, brightly coloured lizard at the bottom of the image: it's a Brazilian galliwasp Diploglossus lessonae. Images (c) Alan Male, from Whitfield (1983).

Diploglossines – popularly called galliwasps – are an extant group of anguid lizards that inhabit South and Central America as well as the Antilles (Anguidae is the group that includes alligator lizards, slow-worms, glass lizards and kin). Most galliwasps are robust-bodied lizards with normally proportioned, complete limbs. A reduced digit count and reduced limb size is, however, present in the obscure taxa Ophiodes, Sauresia and Wetmorena. The vast majority of species are included within Celestus (with about 30 species) and Diploglossus (with about 17 species).

Brilliantly marked Brazilian galliwasp D. lessonae. Image by Torsten Kunsch, CC BY-NC 2.0. Thanks to Fabien Lafuma for sourcing this image.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Galliwasps are superficially skink-like and possess thin, sibcircular osteoderms that give them a shiny, streamlined appearance. The head is often robust and the jaws are powerful (especially in older males), and they can be large overall, the biggest species (the very probably extinct Jamaican giant galliwasp C. occiduus) well exceeding 30 cm in total length. Galliwasps as a whole are long-bodied, typically possessing 31-40 presacral vertebrae, though with 72-74 being present in the anguine-like, near-limbless Ophiodes (Estes 1983).

A juvenile Hispaniolan galliwasp Celestus warreni in captivity; photo by Onagro, CC BY-SA 3.0.

A formidable and striking appearance means that galliwasps often have some significance to local people and are sometimes wrongly regarded as venomous. Jamaican giant galliwasps apparently had some role in certain voodoo traditions. This supposed link to venomosity might explain that weird name they have, though I’ve been unable to ever find out anything specific as goes its origin. It’s said in some sources that galliwasp is actually pre-dated by a 17th century term gallivache, though the etymology of that is mysterious too.

The spectacular Costa Rican rainbow stripe galliwasp D. monotropis. Image (c) Tom Snyder, CC BY 2.0. From here.

Relatively little of known of galliwasp ecology, life history and behaviour. As a generalisation, they’re terrestrial lizards of forest, scrubby or rocky environments, though some have been collected in marshes and swamps. It’s guessed that galliwasps are capable burrowers (either in leaf litter or soft sediment) and there’s also some assumption that they’re crepuscular. A consequence of this sort of lifestyle is that they’re rarely seen and rarely encountered, and some species thought to be rare or even extinct may not be.

They seem to be adaptable and flexible as goes diet: the Jamaican giant galliwasp was reported to eat fruits and other plant parts as well as fish (Schwartz & Henderson 1991), and insects, worms, molluscs and small lizards and mammals have been listed as prey items for other species. Among the most flexible is the island endemic Malpelo or Dotted galliwasp D. millepunctatus of Malpelo Island off the coast of Colombia, a animal described as “curious and opportunistic” (Graham 1975). It eats crabs, amphipods, seabird eggs and carcasses, and seabird droppings. It also mobs seabirds that are bringing food back to their chicks and seems to respond to feeding calls made by young boobies (Kiester 1975). Incidentally, this species also forages at the edge of the sea and has been reported swimming in the sea and entering it voluntarily.

The group includes both oviparous and viviparous species. Juveniles are sometimes very differently patterned and coloured from adults, possessing bold stripes. In some places the juveniles seem to mimic locally occurring toxic millipedes (Pianka & Vitt 2003). While little good data is available, it seems that these lizards are slow to mature and long-lived, larger species maybe taking 3 or 4 years to reach maturity and then living for a few decades at least.

Juvenile Brazilian galliwasp D. lessonae showing characteristic zebra striping of young individuals. Image by Psfaraujo, CC BY-SA 3-0.

Several island-endemic Diploglossus and Celestus species inhabit or inhabited the Antilles, and some have become extinct in historic times due to the introduction of non-native mammals like mongooses. There’s a lot to say about these recently extinct species and I’ll have to promise to come back to them at another time (sorry, this article is intended to be a brief introduction).

Museum specimen of the Jamaican giant galliwasp C. occiduus, photographed at the Natural History Museum, London. Photo (c) Simon J. Tonge, CC BY-SA 3.0, from here.

There are quite a few fossil galliwasps. Diploglossus is known from the Pleistocene and Holocene of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic while Celestus is known from the Pleistocene and/or Holocene of the Dominican Republic and Jamaica. Fossil specimens that have been referred to extant species (including D. pleii on Puerto Rico) are somewhat larger than the biggest members of modern populations (16 cm SVL vs 11 cm) (Estes 1983). A Lower Eocene anguid from Wyoming – Eodiploglossus – has been included within this group and clearly resembles extant galliwasps in osteoderm, tooth and dentary characters. If correctly identified, Eodiploglossus suggests that diploglossines originated in North America before dispersing south to the Antilles and Central and South America.

Long-time readers of Tet Zoo – very long-time readers – might vaguely recall my promise to cover galliwasps way back in about 2007 or something (offending article is here). While this quick article is not the full, detailed review of the group I’d really like to produce, at least it’s something. I’ll return to galliwasps in time, I promise.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on anguids and other lizards, see...

Dibamids and amphisbaenians

Amphisbaenians and the origins of mammals (April 1st article!)

Gekkotans

Gekkota part II: loud voices, hard eggshells and giant calcium-filled neck pouches

Squirting sticky fluid, having a sensitive knob, etc. (gekkotans part III)

300 years of gecko literature, and the ‘Salamandre aquatique’ (gekkotans part VI)

Whence Uroplatus and… there are how many leaf-tailed gecko species now?? (gekkotans part VII)

Ptychozoon: the geckos that glide with flaps and fringes (gekkotans part VIII)

Lacertids

The New Forest Reptile Centre (on Zootoca and Lacerta)

Iguanians

Harduns and toad-heads; a tale of arenicoly and over-looked convergence

The Squamozoic actually happened (kind of): giant herbivorous lizards in the Paleogene

Australia, land of dragons (by which I mean: agamids) (part I)

Scincomorphs

Anguimorphs

Pompey and Steepo, the world-record-holding champion slow-worms

Dinosaurs come out to play (so do turtles, and crocodilians, and Komodo dragons)

What I saw at the zoo yesterday... (more brief comments on Komodo dragons)

Perentie tries to swallow echidna. Echidna too spiky, Perentie gets horribly injured. Dies.

“Lean, green and rarely seen”: enthralling prasinoid tree monitors

Monitor musings, varanid variables, goannasaurian goings-on… it's about monitor lizards

Submarine Tapirs, Sidewinding Anacondas and Other Unusual Animal Behaviors

Snakes

"What was that cute little Mexican snake?", and other musings...

Snake 195 mm long eats centipede 140 mm long. Centipede too big. Snake dies.

Monster pythons of the Everglades: Inside Nature's Giants series 2, part II

The more you know about colubrid snakes, the better a person you are

Love for Mastigodryas, Tomodon, Sordellina and all their buddies: you know it’s right

Refs - -

Estes, R. 1983. Handbuch der Palaeoherpetologie, Teil l0a. Sauria terrestria, Amphisbaenia. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart.

Kiester, A. R. 1975. Notes on the natural history of Diploglossus millepunctatus (Sauria: Anguidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 176, 39-43.

Graham, J. B. 1975. The biological investigation of Malpelo Island, Colombia. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 176, 1-8.

Pianka, E. R. & Vitt, L. J. 2003. Lizards: Windows the Evolution of Diversity. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Schwartz, A. & Henderson, R. W. 1991. Amphibians and Reptiles of the West Indies: Descriptions, Distributions, and Natural History. University of Florida Press, Gainesville.

Whitfield, P. 1983. Reptiles and Amphibians: an Authoritative and Illustrated Guide. Longman, Harlow (UK).