This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Rails (or rallids) are a globally distributed group of gruiform birds, conventionally classified alongside cranes and limpkins, and typically combining omnivorous habits, long toes, and an association with wetlands. Coots, swamphens, moorhens, gallinules and a great many others belong to this group. They’ve never been covered on Tet Zoo in any depth, for which I can only apologise.

It’s a sad fact that I haven't yet seen all that many different rallid species. But here’s one that's familiar and often seen around these parts: the Common moorhen Gallinula chloropus. Moorhens are essentially the same thing as the birds called gallinules. Credit: Darren Naish

Rails have been supremely good at colonising oceanic islands and repeatedly evolving flightlessness. That’s great. But what’s less great is that flightlessness and island endemicity have then left them extremely vulnerable to human hunting, and to the depredations of animals introduced by humans. Work by island bird specialist David Steadman indicates that the majority of the c 2000 island-endemic bird species that formerly inhabited the islands of the tropical Pacific were rails, many of which were lost in recent centuries (Steadman 1995). Many island-dwelling rails were (or are) recent colonisers of the islands, and thus little modified relative to their continental relatives. But some did their colonising far back in the past, and hence had greater time in which to accrue anatomical weirdness. Examples include the tiny, kiwi-like Cabalus of New Zealand, the robust ‘red hen’ Aphanapteryx of Mauritius, and the large, mega-billed takahe species, also of New Zealand.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

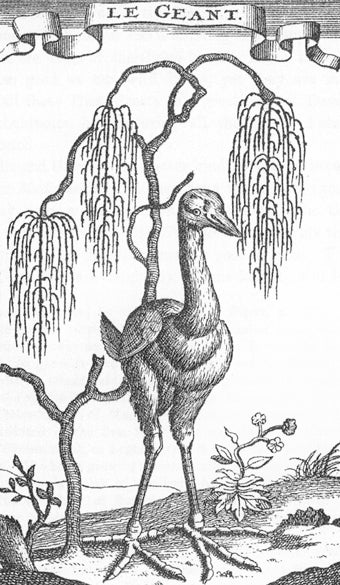

Leguat’s original illustration of ‘Le Géant’, conveniently posed next to what looks like a reasonably large tree. Credit: Yale University Press, New Haven and London

These birds are all remarkable. But exceeding them in the remarkableness stakes is what must have been one of the most striking and bizarre birds of all time: the ridiculous Leguatia gigantea of Mauritius, known as ‘Le Géant of Leguat’ or simply as ‘Le Géant’ or ‘The Giant Bird’, and reported by Hugenot refugee François Leguat following his observations of it during the 1690s. According to Leguat, Le Géant was about 1.8 metres tall, long-necked and long-legged, and almost wholly white in plumage (but for a red patch under the wing). Associated with marshy places, Le Géant had a goose-sized body and bill, long and separated (as in: unwebbed) toes, and a goose-like bill, albeit more pointed. It was flight-capable, despite its size. Leguat published an illustration: this depicts Le Géant as a massive, long-toed bird unlike any known to science. It is shown standing right next to a tree, which does a good job of emphasising its size.

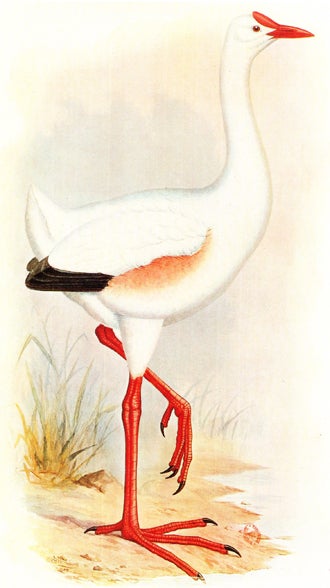

F. W. Frohawk’s beautiful reconstructed of Leguatia, from Rothschild (1907). Credit: Hutchinson, London

In the strict sense – that this was an animal reported through anecdote and unknown from any confirmed specimens – Le Géant might be regarded as a cryptid. However, Leguat’s description was accepted as the valid and reliable description of a hitherto unknown species by several authors, it being German ornithologist Hermann Schlegel who first awarded it a scientific name in 1857. Schlegel thought – based on Leguat’s description of the feet, bill, habitat and overall form of this bird – that it must be a gallinule, and thus a rallid. This view of a 6-foot-tall, white Mauritian gallinule was also adopted by Walter Rothschild who had F. W. Frohawk produce a beautiful life reconstruction of the bird for his 1907 book Extinct Birds (though Frohawk erred in giving the bird black wingtips).

The bird was also discussed at length as a valid entity by Masauji Hachisuka in his remarkable book of 1953, The Dodo and Kindred Birds. This book is “remarkable” because Hachisuka accepted as valid a number of birds known only from anecdote or artwork, including additional dodo and solitaire species and a tortoise-eating endemic corvid he termed the Bi-coloured chough Testudophaga bicolor (Hachisuka 1953). Hachisuka re-affirmed a gallinule identity for Leguatia (he named it the Giant water-hen) and also inadvertently depicted it with black wing-tips (which is amusing since – as pointed out by Fuller (2000) – his footnote apologising for this error features on the same page as his criticism of Frohawk’s depiction of the same mistake).

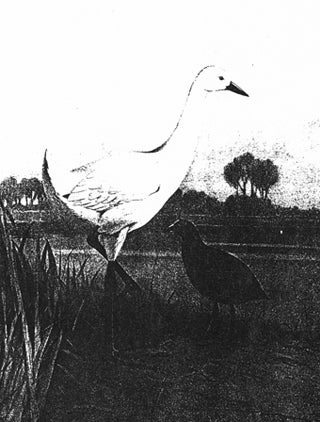

Hachisuka’s illustration of 1953, showing Leguatia to scale with another large rallid (this is the famous ‘oiseau bleu’, a bird known only from eyewitness accounts but considered by Hachisuka to be worthy of the name Cyanornis caerulescens). Credit: H. F. & G. Witherby, London

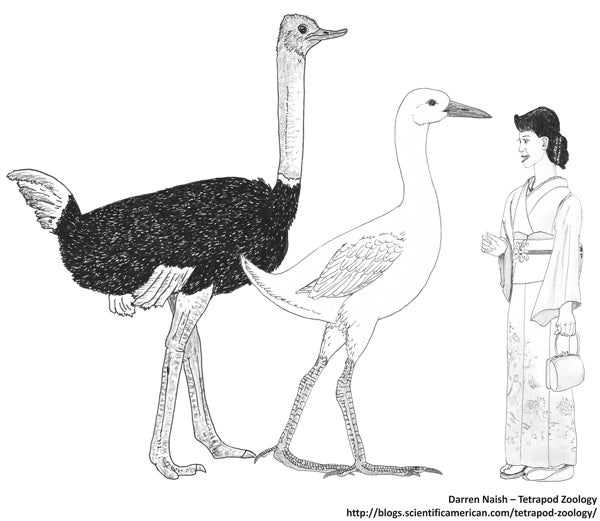

Hachisuka’s work also features another nice reconstruction of the bird in life, this time (helpfully) showing it to scale alongside a more normal (albeit large) gallinule. I only have a low-quality, black and white version of that illustration (a scanned version is shown here), but it inspired the new artwork you see here too. I really want to emphasise what an incredible creature a 6-foot-tall, white gallinule would be. It would be the largest living bird outside the palaeognath clade, and would invite all kinds of questions about rallid evolutionary history, biomechanics and ecology, and in particular would be regarded as an outstanding example of the ‘island effect’ in evolution (where animals variously give rise to unusual giant or dwarf descendants).

Let’s just take a moment to consider how radical the notion of a 6-foot-tall super-rail is. Here’s Leguatia to scale with Struthio camelus and Homo sapiens. Credit: Darren Naish

Several popular books on recently extinct animals have featured Leguatia and accepted it as a valid entity (e.g., Balouet & Alibert 1990), but others have not: it isn’t even mentioned in David Day’s fairly comprehensive The Encyclopedia of Vanished Species (Day 1981).

However, there have long been doubts about this bird’s very existence. Errol Fuller (2000) – in his Extinct Birds – included the species in the ‘Hypothetical Species and Mystery Birds’ section and implied quite strongly that, while Leguat was seemingly reliable as goes some of his observations, we really should doubt the trustworthiness of this specific account. Could it have been a mistake? Could Leguat have seen some other bird and just described it poorly?

Leguatia and the ‘oiseau bleu’ in a scene much inspired by the one from Hachisuka (1953) shown above. Credit: Darren Naish

Actually, this idea is about as old as that promoting the notion of a valid, 6-foot-tall Mauritian super-rail. Suggestions that Leguat might really have observed flamingos have been around since 1781 when they were voiced by Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon in his Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux. If we look at Leguat’s account with a critical eye – and combine it with the fact that flamingo bones are now known from the very Mauritian location where Leguat made his observation – it really has to be concluded that he saw flamingos but confused things with a slightly ‘off’ description (Cheke & Hume 2008). Flamingos became extinct on Mauritius sometime after Leguat’s visit there and their former existence on Mauritius has only recently been confirmed. Authors of previous centuries can, perhaps, be forgiven for not finding this proposal as obvious as we do today.

I’ll just leave this here. These are captive Greater flamingos Phoenicopterus roseus. Credit: Darren Naish

Furthermore, the illustration Leguat provided is not simply not a depiction of what he saw – as many authors have assumed – but a copy of a much older illustration of a bird (an unidentified one, but presumably a rallid of some sort) published by Adriaan Collaert in his Avium Vivae Icones of the late 1500s. Collaert’s bird has no connection with Mauritius at all, is not meant to depict a white super-rail, and is not drawn as being all that big anyway (compare it with the adjacent scoters... the appearance of which emphasises the irrelevance Colleart’s illustration has for the birds of Mauritius).

Colleart’s ‘Avis Indica’ - the long-toed bird on the left and right - shown to scale with two scoters. It’s obvious that the bird on the left (its actual identity is unknown) is the basis for Leguat’s drawing of his Le Géant, shown above. Credit: H. F. & G. Witherby, London

And that is the end of that. Which is a shame.

UPDATE: the original version of this article inadvertently featured the incorrect spellings ‘Legaut’ (for Leguat) and ‘Legautia’ (for Leguatia). Thanks to Max Kirsch for pointing this out.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on rails and other relevant birdy subjects, see...

Getting a major chapter on birds – ALL birds – into a major book on dinosaurs

Katrina van Grouw’s The Unfeathered Bird, a unique inside look

Refs - -

Balouet, J.-C. & Alibert, E. 1990. Extinct Species of the World. Charles Letts & Co., London.

Cheke, A. & Hume, J. 2008. Lost Land of the Dodo. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Day, D. 1981. The Encyclopedia of Vanished Species. London Editions, London.

Fuller, E. 2000. Extinct Birds. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Steadman, D. W. 1995. Prehistoric extinctions of Pacific Island birds: biodiversity seems zooarchaeology. Science 267, 1123-1131.