This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

There are a great many interesting bat groups, and among them are the noctilionids, popularly called bulldog bats or fisherman bats and – less frequently – hare-lipped bats. The group contains but a single living genus (Noctilio) and just two extant species (the Greater bulldog bat N. leporinus and the, ahem, Lesser bulldog bat N. albiventris). They inhabit the northern half of South America, Central America and many of the Antillean islands. Noctilionids are famous for two things: their deeply weird, (vaguely) bulldog-like faces, and their specialisation for grabbing fishes from the water with their massively developed, gaff-like foot claws. Their long legs and well developed, highly mobile calcars are part of this same functional complex. Of the two species, the large (head and body length = c 11-12 cm; wingspan = c 70 cm) N. leporinus is by far more specialised for this lifestyle than is the more insectivorous (and less intensively studied) N. albiventris.

Lesser bulldog bat N. albiventris in hand. The distinctive mouth sharp and large lower canines are obvious; note the rich browny-orange coat colour too. These bats often have a strong musky or fishy odour. Credit: Felineora Wikimedia(CC BY-SA 3.0)

So, these bats are very cool. But much of this stuff is really familiar if you’ve ever read any books on bats, or watched documentaries about them on TV. Here’s we’re going to look at a few things that nobody really talks about: what sort of bats are noctilionids exactly, and what do we know about their evolutionary history?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

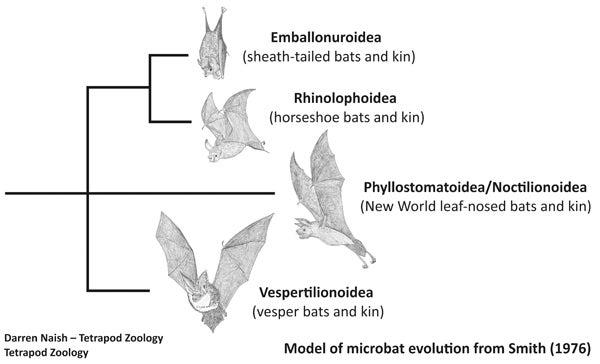

For starters, what are noctilionids? That is, where do they fit within the bat family tree? Views on bat phylogeny were only vaguely enunciated prior to the 1970s (pre-1970s ideas on bat phylogeny are really interesting and I aim to write about them sometime soon), and it was during this decade that Smith (1976) crystallised the idea that noctilionids are part of an exclusively Neotropical group that also includes the phyllostomids* (the Neotropical leaf-nosed bats, one of the largest and most diverse bat groups) and the mormoopids (the naked-backed, moustached or ghost-faced bats). The resultant clade was termed Phyllostomatoidea, even though Noctilionoidea had actual priority (and hence is the name used more frequently today). The precise content of Noctilionoidea has changed somewhat since Smith’s study: in addition to phyllostomids and mormoopids, it also seems to include the Neotropical furipterids (or smoky bats) and thyropterids (or disc-winged bats).

* Read enough bat literature and you’ll see this group name being written Phyllostomidae and Phyllostomatidae interchangeably. The former has priority (Gray 1825 vs Coues & Yarrow 1875) but I don’t know if it’s etymologically correct given that the type genus is Phyllostomus. The same variation is also seen in subfamily, tribe and superfamily-level names, though authors have generally preferred Phyllostomatoidea (over Phyllostomoidea) when writing about the more inclusive group that should properly be called Noctilionoidea.

A phylogeny for noctilionoids as kin as proposed by Smith (1976). This is NOT a contemporary view of bat phylogeny. Over at the Tet Zoo patreon, I’ve been sharing a lot of in-prep bat drawings, all of which are needed for The Big Book. Credit: Darren Naish

Smith (1976) noted that convention at the time proposed the evolution of noctilionoids (note that this term and noctilionids are different and are not being used interchangeably) “from an Old World emballonuroid migrant” (Smith 1976, p. 55). Emballonuroids are another bat group and I’m going to avoid discussing them further here; suffice to say that they include the sheath-tailed bats and sac-winged bats and occur throughout the tropical regions. They were thought to be a sort of grade from which various other bat lineages emerged: the background to this idea is complicated but it was mostly derived from the fact that there are some fairly old emballonuroid fossils. Smith (1976) proposed a new phylogenetic model, positing separate origins of emballonuroids, noctilionoids and other ‘microbat’ lineages from Paleogene bat ancestors.

We know and love Cenozoic South America for all those amazing animals it was previously home to: teratorns, phorusrhacids, sebecosuchians, toxodonts, sparassodonts, astrapotheres, pyrotheres, sloths... this montage has been used at Tet Zoo before but - look! - I've added a noctilionoid bat. Credit: Darren Naish

And, indeed, most (though not all) recent molecular phylogenetic studies do not find emballonuroids to be close to noctilionoids. Instead, noctilionoids are closer to the Australasian mystacinids and to the vespertilionoids – a huge group containing a myriad different lineages. Myzopodids (Madagascan sucker-footed bats) might be part of the noctilionoid clade too. This overall pattern of affinity is suggestive of a Gondwanan centre of origin for noctilionoids and their close relatives though – so far as I can tell – no specific study has attempted to work things out. Our fairly poor knowledge of Paleogene things African and Antarctican means that we can’t take these ideas further for now, though some bat workers have suggested that noctilionoids descended from African ancestors.

Cover of Simpson (1980). Simpson did talk about bats, but only briefly. Credit: Yale University Press, New Haven and London

Whatever the origins of noctilionoids as a whole, the obvious fact is that this group underwent most of its evolution within the Neotropical region – most likely within the northern half of South America – at a time when South America was an island. We’re all familiar with the idea that island South America was home to an amazing assortment of weird placentals like toxodonts and litopterns, the fantastic, omnivorous and predatory sparassodonts, and also to platyrrhine primates and sigmodontine and caviomorph rodents. But bats tend not to get mentioned as part of the same story, even though they clearly should. To be fair, I should note that George Simpson (in his classic work on South American mammals of 1980) did say that South America clearly saw a lot of action as goes bat history, it’s just that the fossil record provides comparatively little illumination on what happened (Simpson 1980).

We will continue this story in the next article. Some of the work here appears as a consequence of the support I receive at patreon.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on bats, see...

Introducing the second largest mammalian ‘family’: vesper bats, or vespertilionids

Bent-winged bats: wide ranges, very weird wings (vesper bats part III)

The many, many mouse-eared bats, aka little brown bats, aka Myotisbats (vesper bats part V)

Long-eared bats proper: Plecotus and other plecotins (vesper bats part VI)

Robust jaws and a (sometimes) ‘greenish’ pelt: house bats (vesper bats part IX)

Antrozoins: pallid bats, Van Gelder’s bat, Rhogeessa… Baeodon!! (vesper bats part XI)

Putting the ‘perimyotines’ well away from pips proper (vesper bats part XII)

Eptesicini: the serotines and their relatives (vesper bats part XIV)

Hypsugines: an assemblage of ‘pipistrelle-like non-pipistrelles’ (vesper bats part XV)

Books of the TetZooniverse: of Palaeoart, Bats, Primates and Crocodylians

Refs - -

Smith, J. D. 1976. Chiropteran Evolution. Texas Tech University, Lubbock.

Simpson, G. G. 1980. Splendid Isolation: the Curious History of South American Mammals. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.