This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

L to r: Carrion crow, juvenile Rook, singing rook, Eurasian jackdaw tearing plastic, Hooded crow eating garbage in Scotland. Photo by Darren Naish.

I’m a huge fan of corvids. I watch and photograph them at every opportunity, and I can easily imagine a life wholly dedicated to, if not obsessed with, these charismatic, amazing, constantly fascinating birds. My experience with the vast majority of corvids (there are about 120 living species) is limited, but the good news is that there’s a nice diversity of these birds to know and love even here in the maritime fringes of north-western Europe.

Legend has it that juvenile birds reach 'adult' size before they do anything outside the nest environment. But that's not always true, as is obvious here. A parent and chick Carrion crow. Photo by Darren Naish.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Carrion crows Corvus corone and Eurasian magpies Pica pica are a constant feature of my living space – literally coming within a few metres of my office on most days of the week – and Rooks C. frugilegus and Eurasian or Western jackdaws C. monedula are a regular presence in the greener spaces a few minutes away from the towns here. The biggest corvid (and one of the biggest of passerines) – the Common raven C. corax – also occurs here in southern England but you might have to make a special effort to see it, and my closest encounters with this species (away from birds in captivity) have been on the Canary Islands. We also have the Eurasian jay Garrulus glandarius here. I see them a lot but my efforts to get good photos have thus far failed. More on that species some other time. And we also have the Hooded crow C. cornix in Scotland and Ireland.

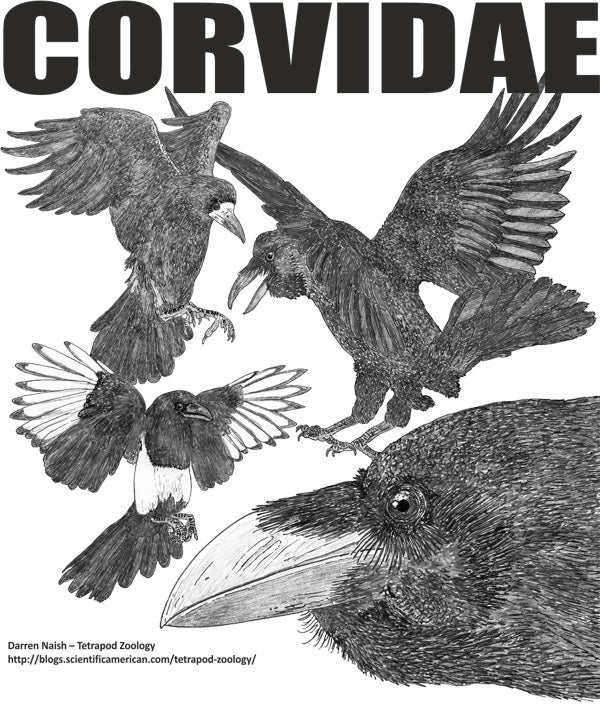

A result of this ever-present assemblage of species is that I have, literally, hundreds of photographs of these several birds, and long-term readers might recall me sharing various of my corvid photos before. The rest of this article serves both as a showcase of some additional photos and as a clearing-house of previous corvid coverage at Tet Zoo. And if you like corvids as much as I do... well, hey, there’s this t-shirt design...

There's corvid merchandise now. Buy it here.

Maybe more on magpies. Magpies – in the sense of the Pica species alone – are, perhaps surprisingly, not close relatives of the assorted long-tailed tropical corvids often called pies, treepies or tropical magpies. Rather, Pica is apparently part of the same clade as true crows, nutcrackers and Old World jays (Ericson et al. 2005). Magpies have done well at adapting to urban environments and have proved adept at exploiting food left by humans and at raiding nest-boxes. I’ve written about magpies at some length before: see this article from June 2013. A pair successfully raised chicks in my front garden in that year and a lot of photos were taken. The same pair didn’t raise chicks here this year, I don’t know why. Here are some photos of one of the adults sunbathing, taken during June 2014 (oh, for more on sunbathing in birds, go here).

Sunbathing magpie. In the image at right, the bird is scratching its head. Note that it's over-wing scratching, not under-wing scratching. Incidentally, the sole of its foot is facing outwards as it does this. Discuss. Photos by Darren Naish.

Bare faces and ‘baggy trousers’: rooks. I’ve written about the Rook previously on Tet Zoo (see this article from 2013). It’s a colonial corvid that possesses a distinctive shaggy plumage and a bill and face specialised for a probing lifestyle. I’m fascinated by the fact that their bill shape varies a great deal according to their habits – look at enough individuals, and you’ll see tremendous variation in bill length, shape and sharpness.

ROOKS. Photos by Darren Naish.

The photos here show rooks stuffing their gular pouches with food, mating, and teaching their chicks how to be a rook. Ok, we’re not supposed to use the word ‘teaching’ when referring to non-humans... what’s the best alternative word?

"This, kids, is how you find stuff on the ground". Rooks in Romania. Photo by Darren Naish.

Surrounded by Carrion crows. The most frequently encountered corvid here (southern England) is the Carrion crow. It doesn’t have any special association with carrion and is a supreme generalist, able to survive about anywhere in Eurasian temperate and subtropical places. I regularly observe mated pairs that forage and hang out together, gangs of juveniles that have a distinct, ‘near-adult’ facial appearance, and chick-adult associations.

Juvenile Carrion crows. Look at those cute, fuzzy little faces. These birds were hanging around at a carpark on a seashore. Photos by Darren Naish.

Carrion crows hate magpies, and noisy battles are a typical (weekly) event in the large trees close to where I live. My impression of what happens goes as follows: a crow pair finds a magpie nest and then seeks to destroy it. The magpies fight back. One or both crows ascends to the top of the tree and calls in reinforcements (this call is different from the typical ‘kraa’ call). More crows arrive. I’ve been aiming to photograph these sorts of events but foliage has made it impossible so far.

Anyway, while Carrion crows mostly occur in pairs, they do form large gatherings on occasion, especially during winter and early spring. The function of these gatherings is unknown. I managed to photograph a gathering involving about 20 crows in March 2015.

Carrion crow aggregation photographed in Southampton, England. Photo by Darren Naish.

Eurasian jackdaws vary in how pale their heads are. The bird above is an English one; those below are Romanian. Photos by Darren Naish.

Coloeus, not Corvus... perhaps. Jackdaws are ‘countryside’ birds here in the UK but they do also occur widely in towns, especially those close to farmland. They’re highly social and are also typically seen in pairs. Their ‘tchak’ calls (Goodwin 1986) often announce their presence before they’re seen. Several jackdaw species occur across Eurasia and northern Africa. The Eurasian jackdaw is variable across its range, populations differing in how dark the cheek, nape and neck are. In western Europe, this whole region is often pretty dark and not so distinct from the rest of the head, but in more eastern populations this region can be almost white. The birds have been split into subspecies on the basis of these plumage differences, but I get the impression that it’s more of a gradational thing.

One more thing on jackdaws... they look so weird compared to other ‘true crows’ (those of the genus Corvus). Their proportions and shape are unlike that of other Corvus species, the big, pale iris is unusual (albeit not unique), and they’re genetically quite distinct from the clade that contains all other Corvus species (Ericson et al. 2005, Haring et al. 2012). For those reasons I admit to being partial to the idea that jackdaws should be recognised as the distinct ‘genus’ Coloeus: this idea is well known among corvid aficionados but hasn’t yet caught on ‘officially’.

The current wallpaper on my laptop. Check out the nasal bristles and throat feathers. La Palma raven, photo by Darren Naish.

The unmistakeable raven. Among the most awesome of corvids is the Common raven, generally just ‘the raven’ to so many people. A graduated tail (this means that the feathers in the middle are longer than the successively shorter feathers on either side), long, glossy throat feathers , an especially big, curved bill and large size make it unmistakeable, and it tends to be associated with mountainous or coastal regions more than other European corvids. Even larger body size and proportionally larger bills are present in the populations of colder places like Greenland and the Himalayas. I had some really neat up-close encounters with a raven pair while on La Palma (Canary Islands) in 2014. These birds sang for human attention and took food from the hand.

Adult male Common raven on La Palma. I love the metallic sheen and fidelity on the feathers. Photo by Darren Naish.

And that’ll do for now. Because corvids are such a constant presence (and so comparatively easy to photograph, plus they’re awesome), the urge to blog about them is always there, so I’m sure we’ll come back to them in time. I’m also now well overdue on my planned review of Gifts of the Crow. On that note, we move on.

There are a few additional relevant Tet Zoo articles on corvids and related passerines too. See...

QUITE POSSIBLY THE BEST VIDEO I’VE EVER SEEN: archosaurs vs mammals (Hooded crows vs cats)

The snood of the turkey, the wires and rackets of the motmot, the face of the rook

Refs - -

Ericson, P. G. P., Jansén, A.-L., Johansson, U. S. & Ekman, J. 2005. Inter-generic relationships of the crows, jays, magpies and allied groups (Aves: Corvidae) based on nucleotide sequence data. Journal of Avian Biology 36, 222-234.

Goodwin, D. 1986. Crows of the World. Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London.

Haring, E., Däubl, B., Kryukov, A. & Gamauf, A. 2012. Genetic divergences and intraspecific variation in corvids of the genus Corvus (Aves: Passeriformes: Corvidae) – a first survey based on museum specimens. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 50, 230-246.