This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

As we get older, a pad of fat under the lower lid of the eye begins to protrude. The physiological shift is colloquially (and much more descriptively) known simply as an "eye bag."—something a lot of people wish would simply go away.

MIT's prolific Robert Langer—holder of more than 1100 issued or pending patents and founder of roughly 30 companies—is lead author on a just-published paper in Nature Materials about a polymer that he compares to a topical version of the body-shaping Spanx. The polymer is applied topically to compress and tighten skin—and, in fact, makes eye bags disappear.

Langer enthuses most about the medical applications for this "second skin," but acknowledges that anti-aging uses are also under consideration. Olivo Labs is the company spun off from another Langer-founded startup to develop the polymer technology. The parent, Living Proof, now makes hair anti-frizz products.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A Q&A with Langer follows.

You have a new paper in the journal Nature Materials called “An Elastic Second Skin.” Can you tell us what that is?

Basically it's kind of a coating you can just apply. In a way it's like an ointment but I guess the way to think about it is that you put it on and then it becomes a solid once it gets on the skin.

So right now if you think about it there's two different things people put on the skin. They put on liquids or ointments or semi-solids and then they also put things on Band-Aids and transdermal patches. This actually gives you the best of both worlds. The ointments are easy to apply but then they don’t necessarily stay on and they're messy. So here you have an ointment that you can apply very easily but then the way we've set up the chemistry, it actually hardens and becomes almost like an invisible Band-Aid for 16 hours.

Can you describe in simple terms chemically how it interacts with the top layer of skin?

Basically what you do is you put this little liquid on that's the polymer. Then you put a second liquid on and that's the catalyst and that causes the cross-linking reaction to occur and that hardens the polymer that conforms right to the skin.

What will it be used for?

That's a very good question. Some of the things we're thinking about are delivering drugs for eczema and psoriasis, and also for anti-aging uses.

When you say anti-aging, what do you mean by that?

For sun damage or if you had dry skin or damaged skin. The skin’s appearance would probably improve if you had dry skin. The formulation can compress the skin. So maybe it could be useful for somebody with Cellulite.

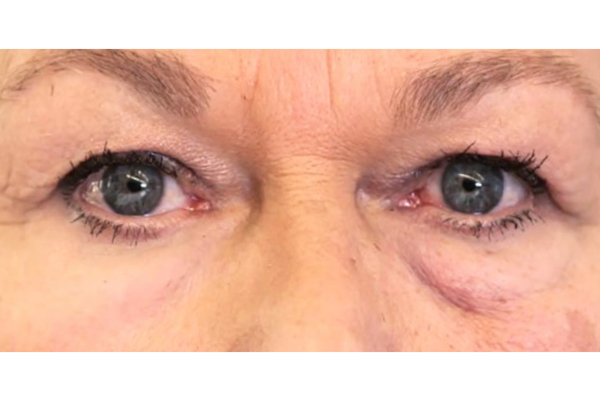

Normal aging also has an effect on the skin and there's a huge market for people who want to have better looking skin who are aging. The photo in the paper showed an immediate effect on aging skin below the eyes and obviously that would be of great interest. Wouldn't it be targeted to that?

We've tried some of that and actually I think it works. On the other hand, certain things are easier to apply than others so I'm not sure whether it’s practical for that. It's just easier to put something on your forearm than near your eye. You can see what you're doing better. And it can't go in your eye. I don't know what would really be best. The medical applications are the ones I’m most excited about.

The skin has a lot of functions. You call it a second skin, but this only performs a few of those functions obviously, right?

Of course.

How do you know that it's safe?

All of the components have been used in patients before and we've it tested it in over 300 people but, that being said, you have to do more. I should say it appears to be safe for everything we've done—the ingredients, their history and the trials that we've done—but none of this has been FDA approved yet.

Check out, too, this video in which Langer and colleagues explain their work.

(Besides Langer, other authors on the paper were Daniel Anderson, Barbara A. Glichrest, Fernanda Skamoto and Rox Anderson of Massachusetts General Hospital; Betty Yu and Soo-Young Kang of Living Proof, Morgan Pilkenton and Alpesh Patel, formerly of Living Proof and Arriya Akthakul, Nithin Ramadurai and Amir Nashat of Olivo Labs.)