This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Last week, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) may have captured the first ever images of the edge of a black hole. As eager astronomers await the arrival of the pictures (which sadly will take a few months, as the hard drives containing them are stuck in Antarctica until the harsh winter gives way to safer flying conditions), the rest of us are left to wonder: what, exactly, should we expect to see? What does a black hole look like, really?

Many of us have seen the standard artist’s representation of a black hole: a giant floating disk with roiling, glowing outer rings and an abruptly dark center from which we’re assured nothing, not even light, can escape. Such images are compelling, but they fail to portray the complex physical forces manifested by the black hole itself. When viewed through a real-life telescope, it turns out these cosmological beasts take a curious shape.

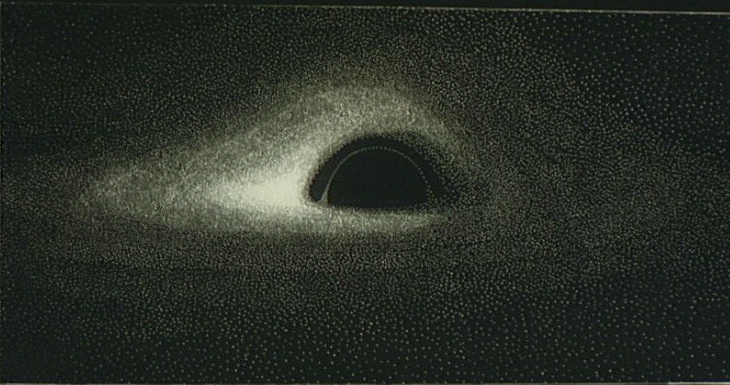

The first to accurately visualize a black hole was a French astrophysicist named Jean-Pierre Luminet. According to a recent Nature blog post by Davide Castelvecchi, in 1978, Luminet used punch cards to write a computer program calculating the appearance of a black hole, and then—in what must have been an equally painstaking process—reproduced the image by hand using India ink on Canson negative paper. The resulting drawing, made of individual dots converging into a pleasantly organic, asymmetrical form, is as visually engaging as it is scientifically revealing.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Jean-Pierre Luminet

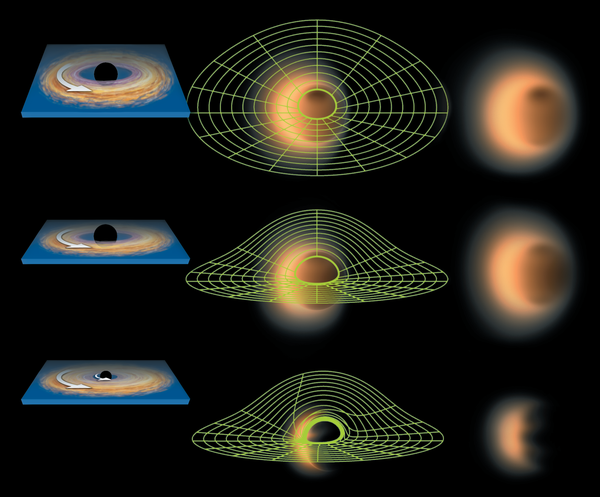

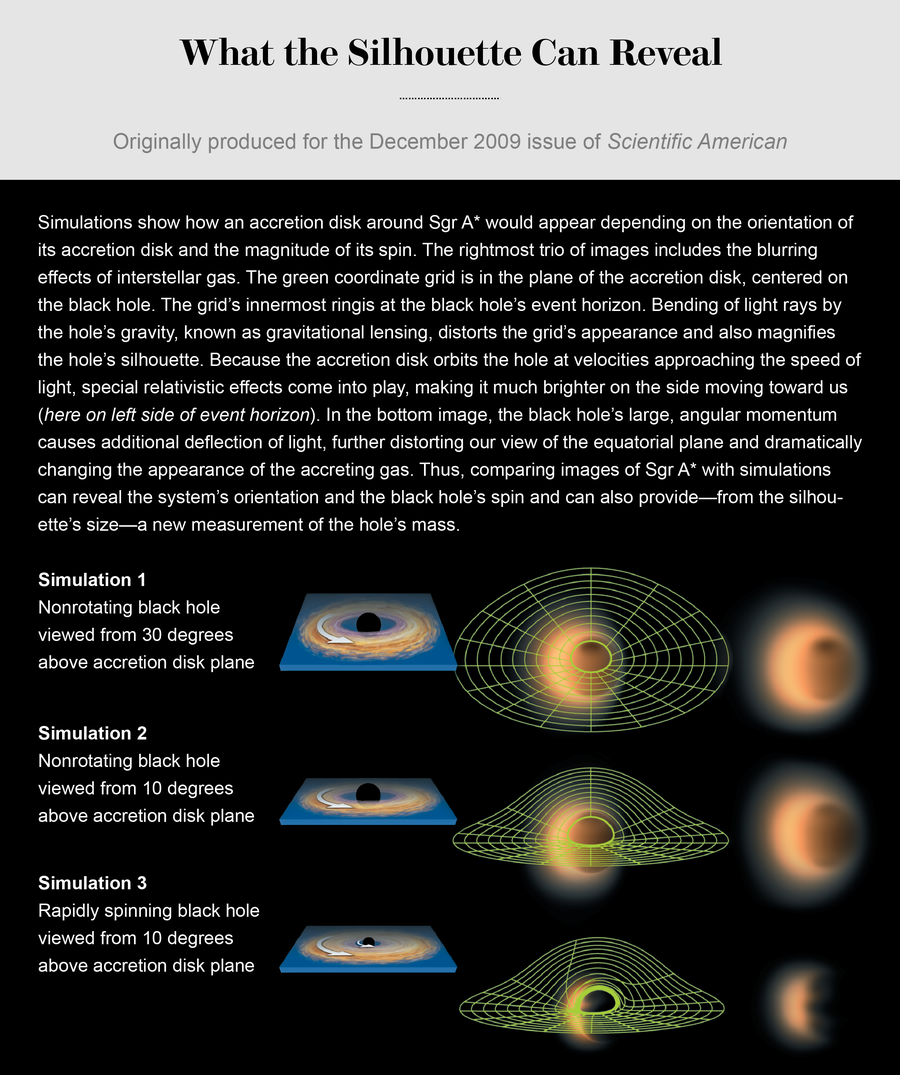

For an explanation of why Luminet’s representation is accurate, check out the graphic below, from the December 2009 issue of Scientific American. You can also read the associated article, “Portrait of a Black Hole,” to find out more about the mission to capture the EHT’s primary target, a supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way known as Sagittarius A*, or Sgr A*.

Source: Avery Broderick (computer simulations)

Credit: Jen Christiansen