This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

On this episode of My Favorite Theorem, my cohost Kevin Knudson and I were happy to talk with Laura Taalman, a math professor at James Madison University. You can listen to the episode here or at kpknudson.com.

Dr. Taalman has worn many mathematical hats over the years, and one of the areas she’s studied is knot theory. Knot theorists study mathematical knots, which are almost the same as the knots in your shoelaces or phone charger cords. You just have to glue the ends of the shoelaces or cords together to get the kind of knot mathematicians study.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

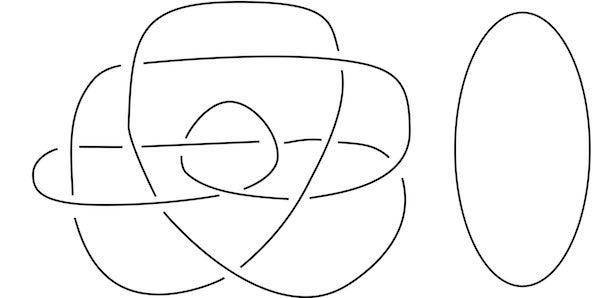

Knots are usually presented as two-dimensional diagrams where strands cross over and under each other, and the most fundamental question in knot theory is when two diagrams of a knot are actually the same knot.

Two diagrams of the same knot (the unknot). The diagram on the left is from Introduction to knot theory by computer by Mitsuyuki Ochiai. Credit: Based on C S and Pbroks13 Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

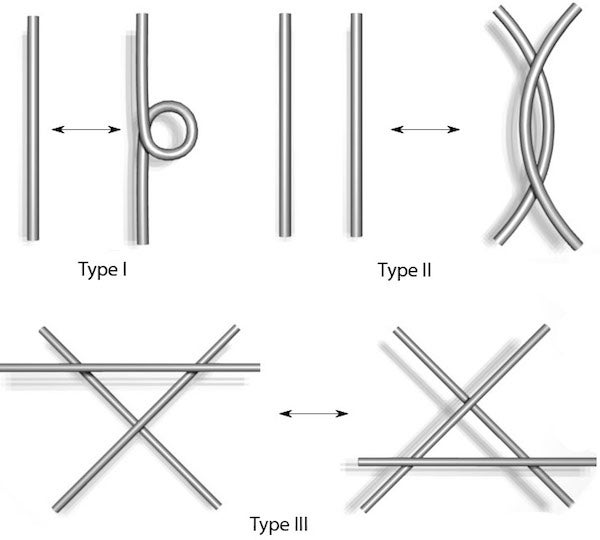

In the 1920s, Kurt Reidemeister and others showed that if two knots are the same, there is a way to turn one diagram into another using a finite sequence of what are known as Reidemeister moves.

A diagram illustrating the three types of Reidemeister moves. Credit: Evelyn Lamb, based on work of Yamashita MakotoWikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

But knowing that two equivalent knot diagrams can be transformed into the same diagram using Reidemeister moves is of limited utility. If you have two diagrams and can’t turn one into the other, how can you tell that it’s because the knots are actually different and not because you just haven’t found the right sequence of moves yet?

Taalman’s favorite theorem gives a way to know for sure whether a knot is equivalent to the unknot, a simple circle. It shows that if the knot is secretly the unknot, there is an upper bound, based on the number of crossings in a diagram of the knot, to the number of Reidemeister moves you will have to do to reduce the knot to a circle. If you try every possible sequence of moves that is at least that long and your diagram never becomes a circle, you know for sure that the knot is really a knot and not an unknot. (Say that ten times fast.)

Taalman loves this theorem not only because it was the first explicit upper bound for the question but also because of how extravagant the upper bound is. In the original paper proving this theorem, Joel Haas and Jeffrey Lagarias got a bound of 2n1011, where n is the number of crossings in the diagram. That’s 2 to the n hundred billionth power. Yikes! When you try to put that number into the online calculator Wolfram Alpha, even for a very small number of crossings, the calculator plays dead.

Dr. Taalman also told us about another paper, this one by Alexander Coward and Marc Lackenby, that bounds the number of Reidemeister moves needed to show whether any two given knot diagrams are equivalent. That bound involves towers of powers that also get comically large incredibly quickly. They’re too big for me to describe how big they are.

Raise a glass to knot theory and big numbers! Credit: Maman Voyage Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

In each episode, we ask our guest to pair their theorem with something. Dr. Taalman chose a nice glass of champagne to celebrate her favorite theorem. You’ll have to listen to the episode to learn why she thinks it’s a perfect match for a knotty theorem.

In addition to her work teaching and doing research, Dr. Taalman worked at the National Museum of Mathematics as mathematician-in-residence for a semester and has worked in the 3D printing industry. She uses 3D printing in her classes now and posts 3D printing tutorials on her blog Hacktastic. Her website is mathgrrl.com, and her Twitter handle is @mathgrrl.

You can find more information about the mathematicians and theorems featured in this podcast, along with other delightful mathematical treats, at kpknudson.com and here at Roots of Unity. A transcript is available here. You can subscribe to and review the podcast on iTunes and other podcast delivery systems. We love to hear from our listeners, so please drop us a line at myfavoritetheorem@gmail.com. Kevin Knudson’s handle on Twitter is @niveknosdunk, and mine is @evelynjlamb. The show itself also has a Twitter feed: @myfavethm and a Facebook page. Join us next time to learn another fascinating piece of mathematics.

Previously on My Favorite Theorem:

Episode 0: Your hosts' favorite theorems Episode 1: Amie Wilkinson’s favorite theorem Episode 2: Dave Richeson's favorite theorem Episode 3: Emille Davie Lawrence's favorite theorem Episode 4: Jordan Ellenberg's favorite theorem Episode 5: Dusa McDuff's favorite theorem Episode 6: Eriko Hironaka's favorite theorem Episode 7: Henry Fowler's favorite theorem Episode 8: Justin Curry's favorite theorem Episode 9: Ami Radunskaya's favorite theorem Episode 10: Mohamed Omar's favorite theorem Episode 11: Jeanne Clelland's favorite theorem Episode 12: Candice Price's favorite theorem Episode 13: Patrick Honner's favorite theorem