This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Euclidean geometry, codified around 300 BCE by Euclid of Alexandria in one of the most influential textbooks in history, is based on 23 definitions, 5 postulates, and 5 axioms, or "common notions." But as I mentioned in my recent post on hyperbolic geometry, one of the postulates, the parallel postulate, is not like the others.

In Thomas Heath's translation of Euclid's Elements (also known as the translation I have), the five postulates are stated as:

"Let the following be postulated:

1) To draw a straight line from any point to any point.

2) To produce a finite straight line continuously in a straight line.

3) To describe a circle with any centre and distance.

4) That all right angles are equal to one another.

5) That, if a straight line falling on two straight lines make the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which are the angles less than the two right angles."

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

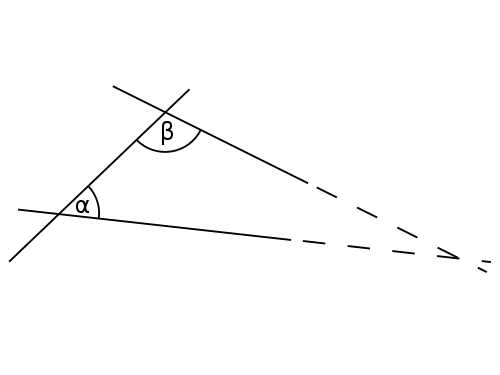

The first four are short and sweet, but the fifth is a mouthful. It's easier to see in a picture.

The parallel postulate says that if the angle measures of α and β add up to less than 180 degrees, then the dotted lines eventually intersect. Credit: 6054, via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0.

The parallel postulate seems natural enough, but it's the kind of statement that seems like it should be a theorem—something we prove using other axioms and postulates—rather than a postulate. For 2000 years, mathematicians tried to prove this, to show that the parallel postulate could be derived from the other axioms and postulates. (For the fascinating story of Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri, one of the mathematicians who tried to do this, check out Thony Christie's blog post the problem with parallels.)

Every attempt at proving the parallel postulate as a theorem was doomed to failure because the parallel postulate is independent from the other axioms and postulates. We can formulate geometry without the parallel postulate, or with a different version of the postulate, in a way that adheres to all the other axioms. Hyperbolic geometry, the subject of my last post, uses a different version of the parallel postulate and therefore ends up with a completely different looking geometry.

I am not a math historian, so my ideas of how it felt to try to prove the parallel postulate are speculative. But I imagine the parallel postulate as a wrinkle in a sheet that moves around when you try to smooth it out but never goes away. People tried to "smooth out" the parallel postulate by proving it, but they only pushed the wrinkle over into some other statement. These statements are fascinating to me. Any one of them can take the place of the parallel postulate, but like the parallel postulate, they can't be proven using only the other postulates and axioms.

Playfair's axiom is probably the simplest statement that is equivalent to the parallel postulate. In fact, I learned it as the parallel postulate: In a plane, given a line and a point not on it, exactly one line parallel to the given line can be drawn through the point.

Playfair's Axiom states that there is only one line through the point P that does not intersect the line L. Credit: Evelyn Lamb.

Playfair's axiom is simple and direct, but some of the most interesting statements that are equivalent to the parallel postulate involve triangles. You probably remember from high school geometry class that the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees. That is only true if you assume the parallel postulate. In fact, it is equivalent to the parallel postulate. But wait, there's more: the statement that all triangles have the same sum of angles is also equivalent to the parallel postulate. I think this is fascinating because it means that in other geometries, there are triangles that have different sums of interior angles! In hyperbolic geometry, for example, the sum of angles can be any number that is less than 180 degrees and greater than or equal to 0 degrees.

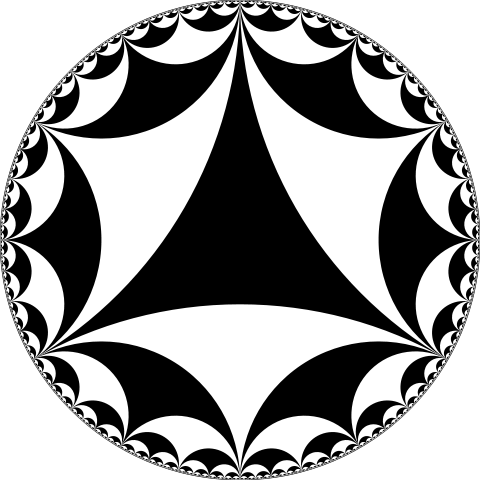

These hyperbolic triangles have angles adding up to 0 degrees. Image: Saric, via Wikimedia Commons.

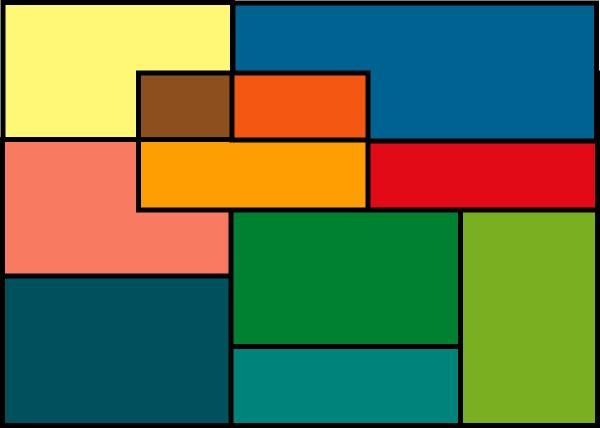

It's not too hard to see that the properties of triangles in different geometries lead to properties of other shapes. For example, Euclidean geometry is the only geometry with rectangles. Why? If you divide a rectangle into two triangles by drawing in one of the diagonals, you end up with two congruent triangles. The rectangle's angles sum up to 360 degrees, so each triangle must have angles that sum up to 180 degrees. If you like rectangles, stick with Euclid.

If you'd like to see these again, you'd better accept the parallel postulate. Credit: Webber, via Wikimedia Commons.

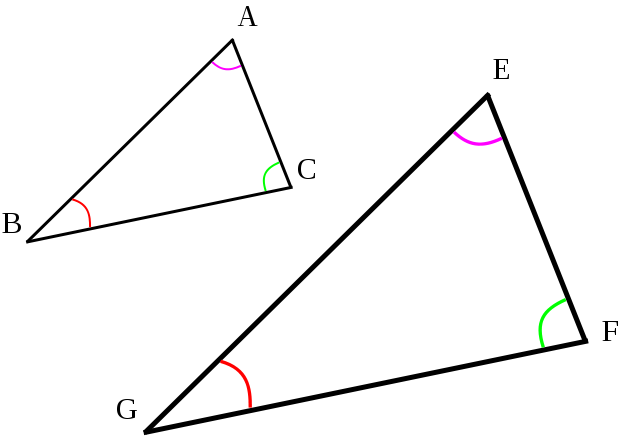

Getting back to triangles, you may remember the ideas of "similar" triangles and "congruent" triangles.Two triangles are similar if they have the same angles and congruent if they are similar and have the same side lengths.

Euclidean triangles that are similar but not congruent. The existence of similar, non-congruent triangles is equivalent to the parallel postulate. Credit: Nguyenthephuc, via Wikimedia Commons.

In Euclidean geometry, there are similar triangles that are not congruent. In fact, there are tons of them. No matter what triangle you start with, you can scale it up or down to whatever size you want. However, the fact that there are similar triangles that are not congruent is very special. It's yet another statement that is equivalent to the parallel postulate! In hyperbolic geometry, for example, the angles of a triangle uniquely determine the lengths of its sides. This has an even more surprising consequence: Euclidean geometry is the only geometry in which triangles can be arbitrarily large. In hyperbolic geometry, there is a largest triangle.

Another statement about triangles that is equivalent to the parallel postulate is the Pythagorean theorem: in a right triangle, the square of the length of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. It's one of the first theorems we learn in geometry, but it's only true if we assume the parallel postulate.

An illustration of the Pythagorean Theorem from Oliver Byrne's 1847 translation of Euclid's Elements. The Pythagorean Theorem states that the sum of the areas of the black and red squares is equal to the area of the yellow and blue square below.

As Alexander Bogomolny writes on his website Cut the Knot, some of the statements that are equivalent to the parallel postulate seem obvious and some do not at all: "By all accounts, the Pythagorean Theorem is far from obvious. It is amazing that the Parallel Postulate, being equivalent to such intuitive statements as [there exists a pair of similar non-congruent triangles] and [there is no upper limit to the area of a triangle], is also equivalent to the Pythagorean Theorem."

As centuries of mathematicians failed to prove the parallel postulate using the other postulates and axioms, I imagine them chugging along, trying to figure out what would happen if they assumed the parallel postulate to be false. They pushed and pushed, but they could never definitively find a contradiction. While they were chugging along, they discovered these statements and many others that are equivalent to the parallel postulate. If you assume any one of them, you end up with Euclidean geometry, but without them, you can find your way to the fantastical land of non-Euclidean geometry where angles determine lengths and there are no squares!